THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL

Standard Library Edition

IN FOUR VOLUMES

VOLUME I

THE LIFE

OF

JOHN MARSHALL

BY

ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE

Volume I

FRONTIERSMAN, SOLDIER

LAWMAKER

1755-1788

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PREFACE

The work of John Marshall has been of supreme importance in the development of the American Nation, and its influence grows as time passes. Less is known of Marshall, however, than of any of the great Americans. Indeed, so little has been written of his personal life, and such exalted, if vague, encomium has been paid him, that, even to the legal profession, he has become a kind of mythical being, endowed with virtues and wisdom not of this earth.

He appears to us as a gigantic figure looming, indistinctly, out of the mists of the past, impressive yet lacking vitality, and seemingly without any of those qualities that make historic personages intelligible to a living world of living men. Yet no man in our history was more intensely human than John Marshall and few had careers so full of movement and color. His personal life, his characteristics and the incidents that drew them out, have here been set forth so that we may behold the man as he appeared to those among whom he lived and worked.

It is, of course, Marshall's public work with which we are chiefly concerned. His services as Chief Justice have been so lauded that what he did before he ascended the Supreme Bench has been almost entirely forgotten. His greatest opinions, however, cannot be fully understood without considering his previous life and experience. An account of Mar[Pg vi]shall the frontiersman, soldier, legislator, lawyer, politician, diplomat, and statesman, and of the conditions he faced in each of these capacities, is essential to a comprehension of Marshall the constructive jurist and of the problems he solved.

In order to make clear the significance of Marshall's public activities, those episodes in American history into which his life was woven have been briefly stated. Although to the historian these are twice-told tales, many of them are not fresh in the minds of the reading public. To say that Marshall took this or that position with reference to the events and questions of his time, without some explanation of them, means little to any one except to the historical scholar.

In the development of his career there must be some clear understanding of the impression made upon him by the actions and opinions of other men, and these, accordingly, have been considered. The influence of his father and of Washington upon John Marshall was profound and determinative, while his life finally became so interlaced with that of Jefferson that a faithful account of the one requires a careful examination of the other.

Vitally important in their effect upon the conduct and attitude of Marshall and of the leading characters of his time were the state of the country, the condition of the people, and the tendency of popular thought. Some reconstruction of the period has, therefore, been attempted. Without a background, the picture and the figures in it lose much of their significance.

The present volumes narrate the life of John Marshall before his epochal labors as Chief Justice began. While this was the period during which events prepared him for his work on the bench, it was also a distinctive phase of his career and, in itself, as important as it was picturesque. It is my purpose to write the final part as soon as the nature of the task permits.

For reading one draft of the manuscript of these volumes I am indebted to Professor Edward Channing, of Harvard University; Dr. J. Franklin Jameson, of the Carnegie Foundation for Historical Research; Professor William E. Dodd, of Chicago University; Professor James A. Woodburn, of Indiana University; Professor Charles A. Beard, of Columbia University; Professor Charles H. Ambler, of Randolph-Macon College; Professor Clarence W. Alvord, of the University of Illinois; Professor D. R. Anderson, of Richmond College; Dr. H. J. Eckenrode, of Richmond College; Dr. Archibald C. Coolidge, Director of the Harvard University Library; Mr. Worthington C. Ford, of the Massachusetts Historical Society; and Mr. Lindsay Swift, Editor of the Boston Public Library. Dr. William G. Stanard, of the Virginia Historical Society, has read the chapters which touch upon the colonial period. I have availed myself of the many helpful suggestions made by these gentlemen and I gratefully acknowledge my obligations to them.

Mr. Swift and Dr. Eckenrode, in addition to reading early drafts of the manuscript, have read the last draft with particular care and I have utilized [Pg viii]their criticisms. The proof has been read by Mr. Swift and the comment of this finished critic has been especially valuable.

I am indebted in the highest possible degree to Mr. Worthington C. Ford, of the Massachusetts Historical Society, who has generously aided me with his profound and extensive knowledge of manuscript sources and of the history of the times of which this work treats. His sympathetic interest and whole-hearted helpfulness have not only assisted me, but encouraged and sustained me in the prosecution of my labors.

In making these acknowledgments, I do not in the least shift to other shoulders the responsibility for anything in these volumes. That burden is mine alone.

I extend my thanks to Mr. A. P. C. Griffin, Assistant Librarian, and Mr. Gaillard Hunt, Chief of the Manuscripts Division, of the Library of Congress, who have been unsparing in their efforts to assist me with all the resources of that great library. The officers and their assistants of the Virginia State Library, the Boston Public Library, the Library of Harvard University, the Manuscripts Division of the New York Public Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Pennsylvania Historical Society, and the Virginia Historical Society have been most gracious in affording me all the sources at their command.

I desire to express my appreciation for original material furnished me by several of the descendants and collateral relatives of John Marshall. Miss [Pg ix]Emily Harvie, of Richmond, Virginia, placed at my disposal many letters of Marshall to his wife. For the use of the book in which Marshall kept his accounts and wrote notes of law lectures, I am indebted to Mrs. John K. Mason, of Richmond. A large number of original and unpublished letters of Marshall were furnished me by Mr. James M. Marshall, of Front Royal, Virginia, Mr. Robert Y. Conrad, of Winchester, Virginia; Mrs. Alexander H. Sands, of Richmond, Virginia; Miss Sallie Marshall, of Leeds, Virginia; Mrs. Claudia Jones, and Mrs. Fannie G. Campbell of Washington, D.C.; Judge J. K. M. Norton, of Alexandria, Virginia; Mr. A. Moore, Jr., of Berryville, Virginia; Dr. Samuel Eliot Morison, of Boston, Massachusetts, and Professor Charles William Dabney, of Cincinnati, Ohio. Complete copies of the highly valuable correspondence of Mrs. Edward Carrington were supplied by Mr. John B. Minor, of Richmond, Virginia, and by Mr. Carter H. FitzHugh, of Lake Forest, Illinois. Without the material thus generously opened to me, this narrative of Marshall's life would have been more incomplete than it is and many statements in it would, necessarily, have been based on unsupported tradition.

Among the many who have aided me, Judge James Keith, of Richmond, Virginia, until recently President of the Court of Appeals of Virginia; Judge J. K. M. Norton and the late Miss Nannie Burwell Norton of Alexandria, Virginia; Mr. William Marshall Bullitt, of Louisville, Kentucky; Mr. Thomas Marshall Smith, of Baltimore, Maryland; Mr. and Mrs. Alexander H. Sands; Mr. W. P. Taylor and Dr. H. [Pg x]Norton Mason, of Richmond, Virginia; Mr. Lucien Keith, Mr. William Horgan, and Mr. William C. Marshall, of Warrenton, Virginia; Judge Henry H. Downing and Mr. Aubrey G. Weaver, of Front Royal, Virginia, have rendered notable assistance in the gathering of data.

I am under particular obligations to Miss Emily Harvie for the use of the striking miniature of Marshall, the reproduction of which appears as the frontispiece to the first volume; to Mr. Roland Gray, of Boston, for the right to reproduce the portrait by Jarvis as the frontispiece of the second volume; to Mr. Douglas H. Thomas of Baltimore, Maryland, for photographs of the portraits of William Randolph, Mary Isham, and Mary Randolph Keith; and to Mr. Charles Edward Marshall, of Glen Mary, Kentucky, for permission to photograph the portrait of Colonel Thomas Marshall.

The large number of citations has made abbreviations necessary. At the end of each volume will be found a careful explanation of references, giving the full title of the work cited, together with the name of the author or editor, and a designation of the edition used.

The index has been made by Mr. David Maydole Matteson, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his careful work has added to whatever of value these volumes possess.

Albert J. Beveridge

CONTENTS

| I. | ANCESTRY AND ENVIRONMENT | 1 |

| The defeat of Braddock—Influence on American opinion—Washington's heroism—Effect on Marshall's parents—Marshall's birth—American solidarity the first lesson taught him—Marshall's ancestry—Curious similarity to that of Jefferson, to whom he was related—The paternal line: the "Marshall legend"—Maternal line: the Randolphs, the Ishams, and the Keiths—Character of Marshall's parents—Colonial Virginia society—Shiftless agriculture and abundant land—Influence of slavery—Jefferson's analysis—Drinking heavy and universal—Education of the gentry and of the common people—The social divisions—Causes of the aristocratic tone of Virginia society—The backwoodsmen—Their character—Superiority of an occasional frontier family—The Marshalls of this class—The illustrious men produced by Virginia just before the Revolution. | ||

| II. | A FRONTIER EDUCATION | 33 |

| Marshall's wilderness birthplace—His father removes to the Blue Ridge—The little house in "The Hollow"—Neighbors few and distant—Daily life of the frontier family—Marshall's delight in nature—Effect on his physical and mental development—His admiration for his father—The father's influence over and training of his son—Books: Pope's Poems—Marshall commits to memory at the age of twelve many passages—The "Essay on Man"—Marshall's father an assistant of Washington in surveying the Fairfax grant—Story of Lord Fairfax—His influence on Washington and on Marshall's father—Effect on Marshall—His father elected Burgess from Fauquier County—Vestryman, Sheriff, and leading man of his county—He buys the land in "The Hollow"—John Thompson, deacon, teaches Marshall for a year—His father buys more land and removes to Oak Hill—Subscribes to the first American edition of Blackstone—Military training interferes with Marshall's reading of Blackstone—He is sent to Campbell's Academy for a few months—Marshall's father as Burgess supports Patrick Henry, who defeats the tidewater aristocracy in the Robinson loan-office contest—Henry offers his resolutions on the Stamp Act: "If this be treason, make the most of it"—Marshall's father votes with Henry—1775 and Henry's "Resolutions for Arming and Defense"—His famous speech: "Give me liberty or give me death"—Marshall's father again supports Henry—Marshall learns from his father of these great events—Father and son ready to take the field against the British.[Pg xii] | ||

| III. | A SOLDIER OF THE REVOLUTION | 69 |

| The "Minute Men" of Virginia—Lieutenant John Marshall drills his company and makes a war speech—His appearance in his nineteenth year—Uniforms of the frontier—The sanguinary fight at Great Bridge—Norfolk—The Marshalls in the Continental service, the father as major, the son as lieutenant—Condition of the army—Confusion of authority—Unreliability of militia "who are here to-day and gone to-morrow"—Fatal effect of State control—Inefficiency and powerlessness of Congress—Destitution of the troops: "our sick naked and well naked"—Officers resign, privates desert—The harsh discipline required: men whipped, hanged, and shot—Impression on Marshall—He is promoted to be captain-lieutenant—The march through disaffected Philadelphia—Marshall one of picked men forming the light infantry—Iron Hill—The battle of the Brandywine—Marshall's father and his Virginians prevent entire disaster—Marshall's part in the battle—The retreat—The weather saves the Americans—Marshall one of rear guard under Wayne—The army recovers and tries to stop the British advance—Confused by false reports of the country people who are against the patriots "almost to a man"—Philadelphia falls—The battle of Germantown—Marshall at the bloodiest point of the fight—The retreat of the beaten Americans—Unreasonable demands of "public opinion"—Further decline of American fortunes—Duché's letter to Washington: "How fruitless the expense of blood"—Washington faces the British—The impending battle—Marshall's vivid description—The British withdraw. | ||

| IV. | VALLEY FORGE AND AFTER | 108 |

| The bitter winter of 1777—The British in Philadelphia: abundance of provisions, warm and comfortable quarters, social gayeties, revels of officers and men—The Americans at Valley Forge, "the most celebrated encampment in the world's history": starvation and nakedness—Surgeon Waldo's diary of "camp-life": "I'll live like a Chameleon upon Air"—Waldo's description of soldiers' appearance—Terrible mortality from sickness—The filthy "hospitals"—Moravians at Bethlehem—The Good Samaritans to the patriots—Marshall's cheerfulness: "the best tempered man I ever knew"—His pranks and jokes—Visitors to the camp remark his superior intelligence—Settles disputes of his comrades—Hard discipline at Valley Forge: a woman given a hundred lashes—Washington alone holds army together—Jealousy of and shameful attacks upon him—The "Conway Cabal"—His dignity in the face of slander—His indignant letter to Congress—Faith of the soldiers in Washington—The absurd popular demand that he attack Philadelphia—The amazing inferiority of Congress—Ablest [Pg xiii]men refuse to attend—Washington's pathetic letter on the subject: "Send your ablest men to Congress; Where is Jefferson"—Talk of the soldiers at Valley Forge—Jefferson in the Virginia Legislature—Comparison of Marshall and Jefferson at this period—Marshall appointed Deputy Judge Advocate of the army—Burnaby's appeal to Washington to stop the war: efforts at reconciliation—Washington's account of the sufferings of the army—The spring of 1778—Sports in camp—Marshall the best athlete in his regiment: "Silver Heels" Marshall—The Alliance with the King of France—Rejoicing of the Americans at Valley Forge—Washington has misgivings—The services of Baron von Steuben—Lord Howe's departure—The "Mischianza"—The British evacuate Philadelphia—The Americans quick in pursuit—The battle of Monmouth—Marshall in the thick of the fight—His fairness to Lee—Promoted to be captain—One of select light infantry under Wayne, assigned to take Stony Point—The assault of that stronghold—Marshall in the reserve command—One of the picked men under "Light Horse Harry" Lee—The brilliant dash upon Powles Hook—Term of enlistment of Marshall's regiment expires and he is left without a command—Returns to Virginia while waiting for new troops to be raised—Arnold invades Virginia—Jefferson is Governor; he fails to prepare—Marshall one of party to attack the British—Effect of Jefferson's conduct on Marshall and the people—Comment of Virginia women—Inquiry in Legislature as to Jefferson's conduct—Effect of Marshall's army experience on his thinking—The roots of his great Nationalist opinions run back to Valley Forge. | ||

| V. | MARRIAGE AND LAW BEGINNINGS | 148 |

| Marshall's romance—Visits his father who is commanding at Yorktown—Mythical story of his father's capture at Charleston—The Ambler family—Rebecca Burwell, Jefferson's early love—Attractiveness of the Amblers—The "ball" at Yorktown—High expectations of the young women concerning Marshall—Their disappointment at his uncouth appearance and rustic manners—He meets Mary Ambler—Mutual love at first sight—Her sister's description of the ball and of Marshall—The courtship—Marshall goes to William and Mary College for a few weeks—Description of the college—Marshall elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society—Attends the law lectures of Mr. Wythe—The Ambler daughters pass though Williamsburg—The "ball" at "The Palace"—Eliza Ambler's account: "Marshall was devoted to my sister"—Marshall leaves college and follows Mary Ambler to Richmond—Secures license to practice law—Resigns his command—Walks to Philadelphia to be inoculated against smallpox—Tavern-keeper refuses to take him in because of his appearance—Returns to Virginia and resumes his courtship of Mary Ambler—Marshall's account of his love-making—His sister-in-law's description [Pg xiv]of Marshall's suit—Marshall's father goes to Kentucky and returns—Marshall elected to the Legislature from Fauquier County—He marries Mary Ambler: "but one solitary guinea left"—Financial condition of Marshall's father at this time—Lack of ready money everywhere—Marshall's account—He sets up housekeeping in Richmond—Description of Richmond at that time—Brilliant bar of the town—"Marshall's slender legal equipment"—The notes he made of Mr. Wythe's lectures—His Account Book—Examples of his earnings and expenditures from 1783 until 1787—Life of the period—His jolly letter to Monroe—His books—Elected City Recorder—Marshall's first notable case: Hite vs. Fairfax—His first recorded argument—His wife becomes an invalid—His tender care of her—Mrs. Carrington's account: Marshall "always and under every circumstance, an enthusiast in love." | ||

| VI. | IN THE LEGISLATURE AND COUNCIL OF STATE | 200 |

| In the House of Delegates—The building where the Legislature met—Costumes and manners of the members—-Marshall's popularity and his father's influence secure his election—He is appointed on important committees—His first vote—examples of legislative business—Poor quality of the Legislature: Madison's disgust, Washington's opinion—Marshall's description and remarkable error—He is elected member of Council of State—Pendleton criticizes the elevation of Marshall—Work as member of Council—Resigns from Council because of criticism of judges—Seeks and secures reëlection to Legislature from Fauquier County—Inaccuracy of accepted account of these incidents—Marshall's letter to Monroe stating the facts—Becomes champion of needy Revolutionary soldiers—Leads fight for relief of Thomas Paine—Examples of temper of the Legislature—Marshall favors new Constitution for Virginia—The "Potowmack Company"—Bills concerning courts—Reform of the High Court of Chancery—The religious controversy—State of religion in Virginia—Marshall's languid interest in the subject—Great question of the British debts—Long-continued fight over payment or confiscation—Marshall steadily votes and works for payment of the debts—Effect of this contest on his economic and political views—His letter to Monroe—Instability of Legislature: a majority of thirty-three changed in two weeks to an adverse majority of forty-nine—No National Government—Resolution against allowing Congress to lay any tax whatever: "May prove destructive of rights and liberties of the people"—The debts of the Confederation—Madison's extradition bill—Contempt of the pioneers for treaties—Settlers' unjust and brutal treatment of the Indians—Struggle over Madison's bill—Patrick Henry saves it—Marshall supports it—Henry's bill for amalgamation of Indians and whites—Marshall [Pg xv]regrets its defeat—Anti-National sentiment of the people—Steady change in Marshall's ideas—Mercantile and financial interests secure the Constitution—Shall Virginia call a Convention to ratify it?—Marshall harmonizes differences and Convention is called—He is in the first clash over Nationalism. | ||

| VII. | LIFE OF THE PEOPLE: COMMUNITY ISOLATION | 250 |

| The state of the country—A résumé of conditions—Revolutionary leaders begin to doubt the people—Causes of this doubt—Isolation of communities—Highways and roads—Difficulty and danger of travel—The road from Philadelphia to Boston: between Boston and New York—Roads in interior of New England, New York, Philadelphia, and New Jersey—Jefferson's account of roads from Richmond to New York—Traveler lost in the "very thick woods" on way from Alexandria to Mount Vernon to visit Washington—Travel and transportation in Virginia—Ruinous effect on commerce—Chastellux lost on journey to Monticello to visit Jefferson—Talleyrand's description of country—Slowness of mails—Three weeks or a month and sometimes two months required between Virginia and New York—Mail several months in reaching interior towns—News that Massachusetts had ratified the Constitution eight days in reaching New York—Ocean mail service—letters opened by postmasters or carriers—Scarcity of newspapers—Their untrustworthiness—Their violent abuse of public men—Franklin's denunciation of the press: he advises "the liberty of the cudgel" to restrain "the liberty of the press"—Jefferson's disgust—The country newspaper: Freneau's "The Country Printer"—The scantiness of education—Teachers and schools—The backwoodsmen—The source of abnormal American individualism—The successive waves of settlers—Their ignorance, improvidence, and lack of social ideals—Habits and characteristics of Virginians—Jefferson's harsh description of them—Food of the people—Their houses—Continuous drinking of brandy, rum, and whiskey—This common to whole country—Lack of community consciousness—Abhorrence of any National Government. | ||

| VIII. | POPULAR ANTAGONISM TO GOVERNMENT | 288 |

| Thomas Paine's "Common Sense"—Its tremendous influence: "Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil"—Popular antagonism to the very idea of government—Impossibility of correcting falsehoods told to the people—Popular credulity—The local demagogue—North Carolina preacher's idea of the Constitution—Grotesque campaign story about Washington and Adams—Persistence of political canard against Levin Powell—Amazing statements about the Society of the Cincinnati: Ædanus Burke's pamphlet; Mirabeau's pamphlet; Jefferson's [Pg xvi]denunciation—Marshall and his father members of the Cincinnati—Effect upon him of the extravagant abuse of this patriotic order—Popular desire for general division of property and repudiation of debts—Madison's bitter comment—Jay on popular greed and "impatience of government"—Paper money—Popular idea of money—Shays's Rebellion—Marshall's analysis of its objects—Knox's report of it—Madison comes to the conclusion that "the bulk of mankind" are incapable of dealing with weighty subjects—Washington in despair—He declares mankind unfit for their own government—Marshall also fears that "man is incapable of governing himself"—Jefferson in Paris—Effect on his mind of conditions in France—His description of the French people—Jefferson applauds Shays's Rebellion: "The tree of liberty must be refreshed by the blood of patriots and tyrants"—Influence of French philosophy on Jefferson—The impotence of Congress under the Confederation—Dishonorable conduct of the States—Leading men ascribe evil conditions to the people themselves—Views of Washington, Jay, and Madison—State Sovereignty the shield of turmoil and baseness—Efforts of commercial and financial interests produce the Constitution—Madison wants a National Government with power of veto on all State laws "whatsoever"—Jefferson thinks the Articles of Confederation "a wonderfully perfect instrument"—He opposes a "strong government"—Is apprehensive of the Constitution—Thinks destruction of credit a good thing—Wishes America "to stand with respect to Europe precisely on the footing of China"—The line of cleavage regarding the Constitution—Marshall for the Constitution. | ||

| IX. | THE STRUGGLE FOR RATIFICATION | 319 |

| The historic Convention of 1788 assembles—Richmond at that time—General ignorance of the Constitution—Even most members of the Convention poorly informed—Vague popular idea of Constitution as something foreign, powerful, and forbidding—People in Virginia strongly opposed to it—The Virginia debate to be the greatest ever held over the Constitution—The revolutionary character of the Constitution: would not have been framed if the people had known of the purposes of the Federal Convention at Philadelphia: "A child of fortune"—Ratification hurried—Pennsylvania Convention: hastily called, physical violence, small number of people vote at election of members to Pennsylvania Convention—People's ignorance of the Constitution—Charges of the opposition—"The humble address of the low born"—Debate in Pennsylvania Convention—Able "Address of Minority"—Nationalism of the Constitution the principal objection—Letters of "Centinel": the Constitution "a spurious brat"—Attack on Robert Morris—Constitutionalist replies: "Sowers of sedition"—Madison alarmed—The struggle in [Pg xvii]Massachusetts—Conciliatory tactics of Constitutionalists—Upper classes for Constitution—Common people generally opposed—Many towns refuse to send delegates to the Convention—Contemporary descriptions of the elections—High ability and character of Constitutionalist members—Self-confessed ignorance and incapacity of opposition: Madison writes that there is "Scarcely a man of respectability among them"—Their pathetic fight against the Constitution—Examples of their arguments—The bargain with Hancock secures enough votes to ratify—The slender majority: one hundred and sixty-eight vote against ratification—Methods of Constitutionalists after ratification—Widgery's amusing account: hogsheads of rum—Gerry's lament—Bribery charged—New Hampshire almost rejects Constitution—Convention adjourned to prevent defeat—"Little information among the people," but most "men of property and abilities" for Constitution—Constitution receives no deliberate consideration until debated in the Virginia Convention—Notable ability of the leaders of both sides in the Virginia contest. | ||

| X. | IN THE GREAT CONVENTION | 357 |

| Virginia the deciding State—Anxiety of Constitutionalists in other States—Hamilton writes Madison: "No hope unless Virginia ratifies"—Economic and political importance of Virginia—Extreme effort of both sides to elect members to the Convention—Preëlection methods of the Constitutionalists—They capture Randolph—Marshall elected from opposition constituency—Preëlection methods of Anti-Constitutionalists—The Convention meets—Neither side sure of a majority—Perfect discipline and astute Convention tactics of the Constitutionalists—They secure the two powerful offices of the Convention—The opposition have no plan of action—Description of George Mason—His grave error in parliamentary tactics—Constitutionalists take advantage of it: the Constitution to be debated clause by clause—Analysis of the opposing forces: an economic class struggle, Nationalism against provincialism—Henry tries to remedy Mason's mistake—Pendleton speaks and the debate begins—Nicholas speaks—His character and personal appearance—Patrick Henry secures the floor—Description of Henry—He attacks the Constitution: why "we the people instead of we the States"? Randolph replies—His manner and appearance—His support of the Constitution surprises the opposition—His speech—His about-face saves the Constitution—The Clinton letter: if Randolph discloses it the Anti-Constitutionalists will win—He keeps it from knowledge of the Convention—Decisive importance of Randolph's action—His change ascribed to improper motives—Mason answers Randolph and again makes tactical error—Madison fails to speak—Description of Edmund [Pg xviii]Pendleton—He addresses the Convention: "the war is between government and licentiousness"—"Light Horse Harry" Lee—The ermine and the sword—Henry secures the floor—His great speech: the Constitution "a revolution as radical as that which separated us from Great Britain"—The proposed National Government something foreign and monstrous—"This government is not a Virginian but an American government"—Marshall studies the arguments and methods of the debaters—Randolph answers Henry: "I am a child of the Revolution"—His error concerning Josiah Philips—His speech ineffective—Description of James Madison—He makes the first of his powerful expositions of the Constitution, but has little or no effect on the votes of the members—Speech of youthful Francis Corbin—Randolph's futile effort—Madison makes the second of his masterful speeches—Henry replies—His wonderful art—He attacks Randolph for his apostasy—He closes the first week's debate with the Convention under his spell. | ||

| XI. | THE SUPREME DEBATE | 401 |

| Political managers from other States appear—Gouverneur Morris and Robert Morris for the Constitutionalists and Eleazer Oswald for the opposition—Morris's letter: "depredations on my purse"—Grayson's letter: "our affairs suspended by a thread"—Opening second week of the debate—The New Academy crowded—Henry resumes his speech—Appeals to the Kentucky members, denounces secrecy of Federal Convention, attacks Nationalism—Lee criticizes lobbying "out of doors" and rebukes Henry—Randolph attacks Henry: "If our friendship must fall, let it fall like Lucifer, never to rise again"—Randolph challenges Henry: a duel narrowly averted—Personal appearance of James Monroe—He speaks for the Revolutionary soldiers against the Constitution and makes no impression—Marshall put forward by the Constitutionalists—Description of him: badly dressed, poetic-looking, "habits convivial almost to excess"—Best-liked man in the Convention; considered an orator—Marshall's speech: Constitutionalists the "firm friends of liberty"; "we, sir, idolize democracy"; only a National Government can promote the general welfare—Marshall's argument his first recorded expression on the Constitution—Most of speech on necessity of providing against war and inspired by his military experience—Description of Benjamin Harrison—Mason attacks power of National taxation and sneers at the "well-born"—He denounces Randolph—Lee answers with a show of anger—William Grayson secures the floor—His character, attainments, and appearance—His learned and witty speech: "We are too young to know what we are good for"—Pendleton answers: "government necessary to protect liberty"—Madison makes his fourth great argument—Henry replies: "the tyranny of Philadelphia [National Government] may be like the tyranny of George III, a horrid, wretched, dreadful picture"; [Pg xix]Henry's vision of the West—Tremendous effect on the Convention—Letter of Gouverneur Morris to Hamilton describing the Convention—Madison's report to Hamilton and to Washington: "the business is in the most ticklish state that can be imagined"—Marshall speaks again—Military speech: "United we are strong, divided we fall"—Grayson answers Marshall—Mason and Henry refer to "vast speculations": "we may be taxed for centuries to give advantage to rapacious speculators"—Grayson's letter to Dane—The advantage with the Anti-Constitutionalists at the end of the second week. | ||

| XII. | THE STRATEGY OF VICTORY | 444 |

| The climax of the fight—The Judiciary the weakest point for the Constitutionalists—Reasons for this—Especially careful plans of the Constitutionalists for this part of the debate—Pendleton expounds the Judiciary clause—Mason attacks it—His charge as to secret purpose of many Constitutionalists—His extreme courtesy causes him again to make a tactical error—He refers to the Fairfax grant—A clever appeal to members from the Northern Neck—Madison's distinguished address—Henry answers Madison—His thrilling speech: "Old as I am, it is probable I may yet have the appellation of rebel. As to this government [the Constitution] I despise and abhor it"—Marshall takes the floor—Selected by the Constitutionalists to make the principal argument for the Judiciary clause—His speech prepared—The National Judiciary "will benefit collective Society"; National Courts will be as fair as State Courts; independence of judges necessary; if Congress should pass an unconstitutional law the National Courts "would declare it void"; they alone the only "protection from an infringement of the Constitution"; State courts "crowded with suits which the life of man will not see determined"; National Courts needed to relieve this congestion; under the Constitution, States cannot be sued in National Courts; the Constitution does not exclude trial by jury: "Does the word court only mean the judges?"; comparison with the Judiciary establishment of Virginia; reply to Mason's argument on the Fairfax title; "what security have you for justice? The independence of your Judiciary!"—Marshall's speech unconnected and discursive, but the Constitutionalists rest their case upon it—Madison's report to Hamilton: "If we can weather the storm against the Judiciary I shall hold the danger to be pretty well over"—Anti-Constitutionalists try to prolong debate until meeting of Legislature which is strongly against the Constitution—Secession threatened—Madison's letter to Hamilton—Contest so close that "ordinary casualties may vary the result"—Henry answers Marshall—His compliment to the young lawyer—His reference to the Indians arouses Colonel Stephen who harshly assails Henry—Nicholas insults Henry, who demands an [Pg xx]explanation—Debate draws to a close—Mason intimates forcible resistance to the Constitution—Lee rebukes him—The Constitutionalists forestall Henry and offer amendments—Henry's last speech: "Nine-tenths of the people" against the Constitution; Henry's vision of the future; a sudden and terrific storm aids his dramatic climax; members and spectators in awe—The Legislature convenes—Quick, resolute action of the Constitutionalists—Henry admits defeat—The Virginia amendments—Absurdity of some of them—Necessary to secure ratification—Marshall on the committee to report amendments—Constitutionalists win by a majority of only ten—Of these, two vote against their instructions and eight vote against the well-known desires of their constituents—The Clinton letter at last disclosed—Mason's wrath—Henry prevents Anti-Constitutionalists from talking measures to resist the new National Government—Washington's account: "Impossible for anybody not on the spot to conceive what the delicacy and danger of our situation have been." | ||

| APPENDIX | 481 | |

| I. Will of Thomas Marshall, "Carpenter" | 483 | |

| II. Will of John Marshall "of the Forest" | 485 | |

| III. Deed of William Marshall to John Marshall "of the Forest" | 487 | |

| IV. Memorial of Thomas Marshall for Military Emoluments | 489 | |

| WORKS CITED IN THIS VOLUME | 491 | |

ILLUSTRATIONS

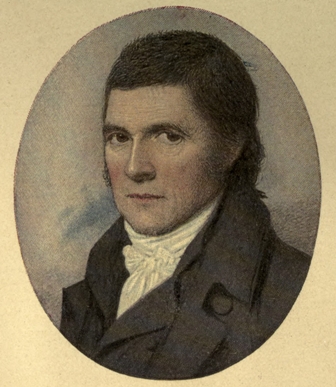

| JOHN MARSHALL AT 43 | Colored Frontispiece |

| From a miniature painted on ivory by an unknown artist. It was executed in Paris in 1797-98, when Marshall was there on the X. Y. Z. Mission. It is now in the possession of Miss Emily Harvie, of Richmond, Virginia. It is the only portrait in existence of Marshall at this period of his life and faithfully portrays him as he was at the time of his intellectual duel with Talleyrand. | |

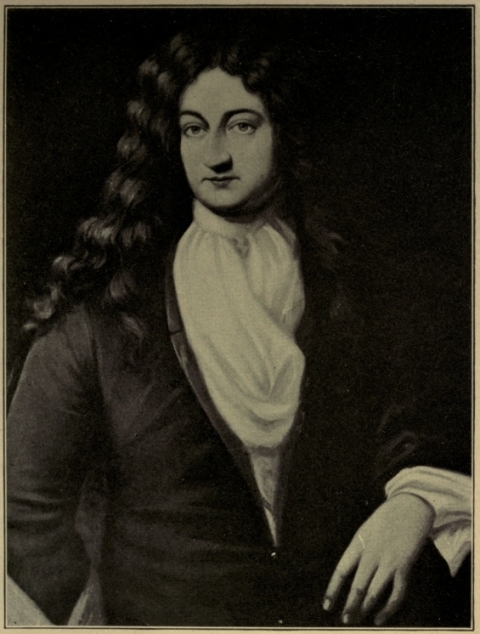

| COLONEL WILLIAM RANDOLPH | 10 |

| From a copy in the possession of Mr. Douglas H. Thomas, of Baltimore, after the original portrait in the possession of Mr. Edward C. Mayo, of Richmond. The painter of the original is unknown. It was painted about 1673 and has passed down through successive generations of the family. Mr. Thomas's copy is a faithful one, and has been used for reproduction here because the original is not sufficiently clear and distinct for the purpose. | |

| MARY ISHAM RANDOLPH, WIFE OF COLONEL WILLIAM RANDOLPH | 10 |

| From a copy in the possession of Mr. Douglas H. Thomas, of Baltimore, after the original in the possession of Miss Anne Mortimer Minor. The original portrait was painted about 1673 by an unknown artist. It is incapable of satisfactory reproduction. | |

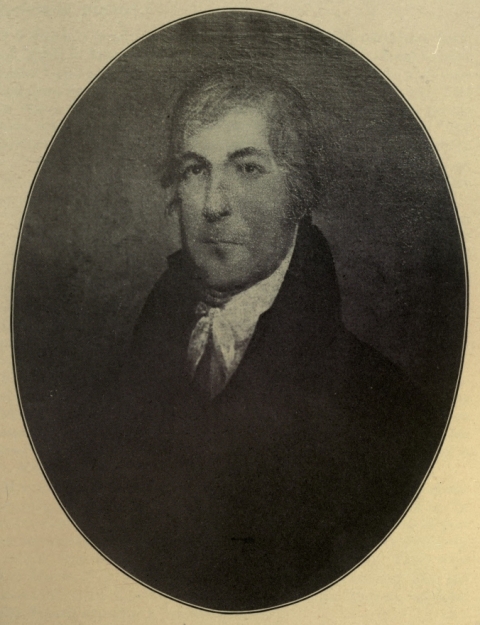

| COLONEL THOMAS MARSHALL, THE FATHER OF JOHN MARSHALL | 14 |

| From a portrait in the possession of Charles Edward Marshall, of Glen Mary, Kentucky. This is the only portrait or likeness of any kind in existence of John Marshall's father. It was painted at some time between 1790 and 1800 and was inherited by Charles Edward Marshall from his parents, Charles Edward and Judith Langhorne Marshall. The name of the painter of this unusual portrait is not known. | |

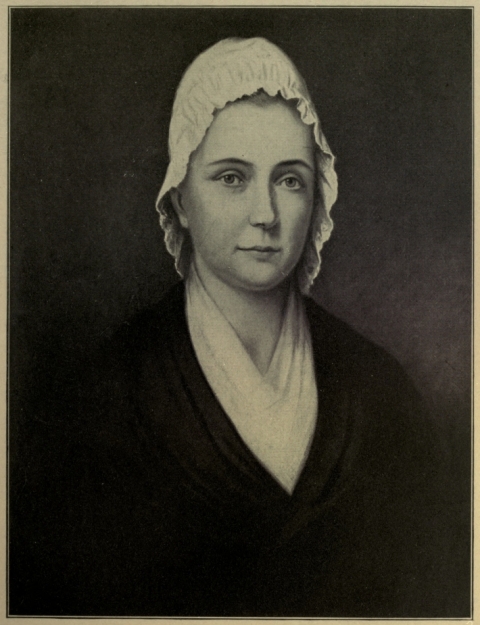

| MARY RANDOLPH (KEITH) MARSHALL, WIFE OF THOMAS MARSHALL AND MOTHER OF JOHN MARSHALL | 18 |

| From a portrait in the possession of Miss Sallie Marshall, of Leeds, Virginia. The portrait was painted at some time between 1790 and 1800, but the painter's name is unknown. The reproduction is from a photograph furnished by Mr. Douglas H. Thomas.[Pg xxii] | |

| "THE HOLLOW" | 36 |

| The Blue Ridge home of the Marshall family where John Marshall lived from early childhood to his eighteenth year. The house is situated on a farm at Markham, Va. From a photograph. | |

| OAK HILL | 56 |

| From a water-color in the possession of Mr. Thomas Marshall Smith, of Baltimore. The small house at the rear of the right of the main building was the original dwelling, built by John Marshall's father in 1773. The Marshall family lived here until after the Revolution. The large building was added nearly forty years afterward by Thomas Marshall, son of the Chief Justice. The name of the painter is unknown. | |

| OAK HILL | 64 |

| This is the original house, built in 1773 and carefully kept in repair. The brick pavement is a modern improvement. From a photograph. | |

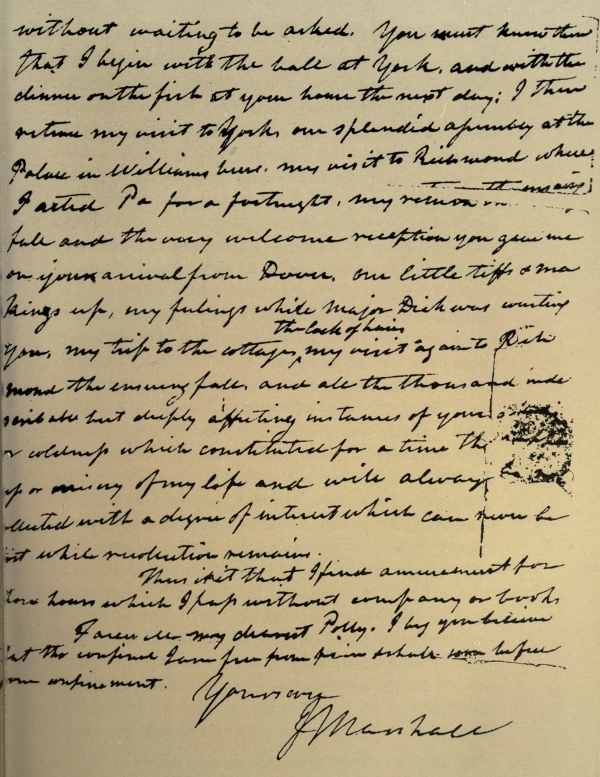

| FACSIMILE OF THE LAST PAGE OF A LETTER FROM JOHN MARSHALL TO HIS WIFE, DESCRIBING THEIR COURTSHIP | 152 |

| This letter was written at Washington, February 23, 1824, forty-one years after their marriage. No part of it has ever before been published. | |

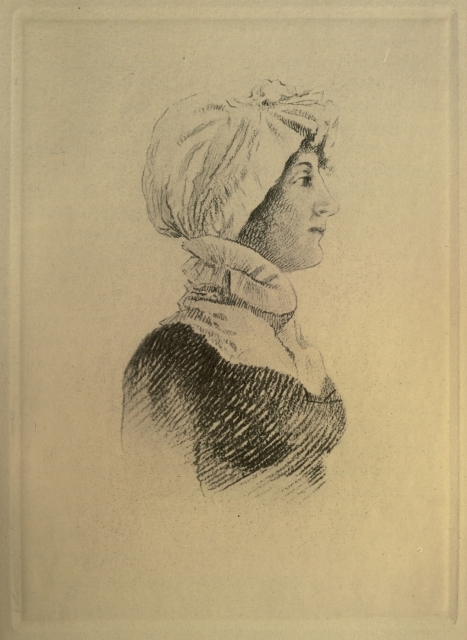

| MARY AMBLER MARSHALL, THE WIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL | 168 |

| A crayon drawing from the original painting now in the possession of Mrs. Carroll, a granddaughter of John Marshall, living at Leeds Manor, Va. This is the only painting of Mrs. Marshall in existence and the name of the artist is unknown. | |

| RICHMOND IN 1800 | 184 |

| From a painting in the rooms of the Virginia Historical Society. | |

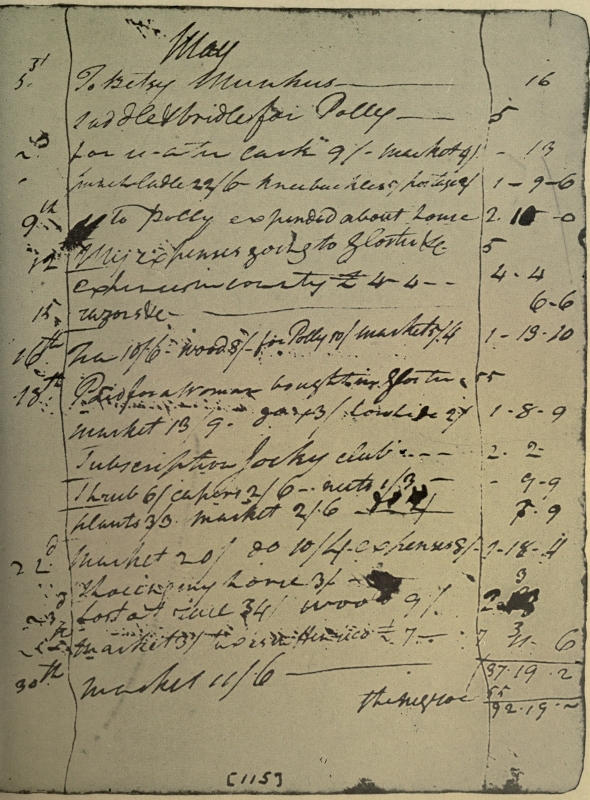

| FACSIMILE OF A PAGE OF MARSHALL'S ACCOUNT BOOK, MAY, 1787 | 198 |

| In this book Marshall kept his accounts of receipts and expenses for twelve years after his marriage in 1783. In the first part of it he also recorded his notes of law lectures during his brief attendance at William and Mary College. The original volume is owned by Mrs. John K. Mason, of Richmond.[Pg xxiii] | |

| FACSIMILES OF SIGNATURES OF JOHN MARSHALL AT TWENTY-NINE AND FORTY-TWO AND OF THOMAS MARSHALL | 210 |

| These signatures are remarkable as showing the extreme dissimilarity between the signature of Marshall as a member of the Council of State before he was thirty and his signature in his mature manhood, and also as showing the basic similarity between the signatures of Marshall and his father. The signature of Marshall as a member of the Council of State in 1784 is from the original minutes of the Council in the Archives of the Virginia State Library. His 1797 signature is from a letter to his wife, the original of which is in the possession of Miss Emily Harvie, of Richmond. The signature of Thomas Marshall is from the original roster of the officers of his regiment in the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress. | |

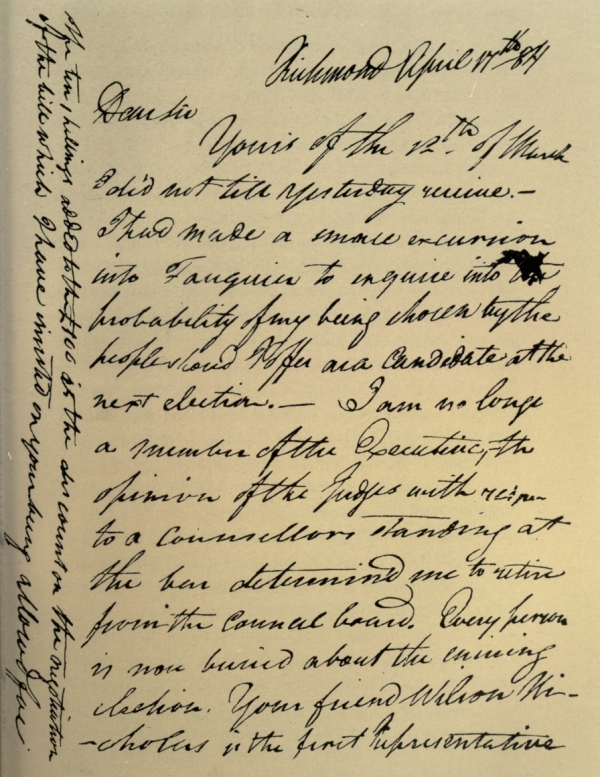

| FACSIMILE OF THE FIRST PAGE OF A LETTER FROM MARSHALL TO JAMES MONROE, APRIL 17, 1784 | 212 |

| From the original in the Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. This letter has never before been published. It is extremely important in that it corrects extravagant errors concerning Marshall's resignation from the Council of State and his reëlection to the legislature. | |

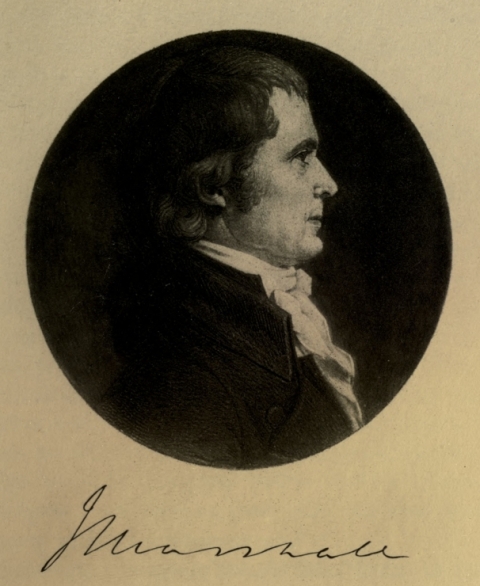

| JOHN MARSHALL | 294 |

| From a profile drawing by Charles Balthazar Julien Fèvre de Saint Mémin, in the possession of Miss Emily Harvey of Richmond, Va., a granddaughter of John Marshall. Autograph from manuscript collection in the Library of the Boston Athenæum. | |

| GEORGE WYTHE | 368 |

| From an engraving by J. B. Longacre after a portrait by an unknown painter in the possession of the Virginia State Library. George Wythe was Professor of Law at William and Mary College during Marshall's brief attendance. | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | 420 |

| From a painting by J. B. Martin in the Robe Room of the Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, D.C. | |

| PATRICK HENRY | 470 |

| From a copy (in the possession of the Westmoreland Club, of Richmond) of the portrait by Thomas Sully. Sully, who never saw Patrick Henry himself, painted the portrait from a miniature on ivory done by a French artist in Richmond about 1792. John Marshall, under date of December 30, 1816, attested its excellence as follows: "I have been shown a painting of the late Mr. Henry, painted by Mr. Sully, now in possession of Mr. Webster, which I think a good likeness." |

LIST OF ABBREVIATED TITLES MOST FREQUENTLY CITED

All references here are to the List of Authorities at the end of this volume.

Beard: Econ. I. C. See Beard, Charles A. Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.

Beard: Econ. O. J. D. See Beard, Charles A. Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy.

Bruce: Econ. See Bruce, Philip Alexander. Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeeth Century.

Bruce: Inst. See Bruce, Philip Alexander. Institutional History of Virginia in the Seventeeth Century.

Cor. Rev.: Sparks. See Sparks, Jared. Correspondence of the Revolution.

Eckenrode: R. V. See Eckenrode, H. J. The Revolution in Virginia.

Eckenrode: S. of C. and S. See Eckenrode, H. J. Separation of Church and State in Virginia.

Jefferson's Writings: Washington. See Jefferson, Thomas. Writings. Edited by H. A. Washington.

Monroe's Writings: Hamilton. See Monroe, James. Writings. Edited by Stanislaus Murray Hamilton.

Old Family Letters. See Adams, John. Old Family Letters. Edited by Alexander Biddle.

Wertenbaker: P. and P. See Wertenbaker, Thomas J. Patrician and Plebeian in Virginia; or the Origin and Development of the Social Classes of the Old Dominion.

Wertenbaker: V. U. S. See Wertenbaker, Thomas J. Virginia Under the Stuarts, 1607-1688.

Works: Adams. See Adams, John. Works. Edited by Charles Francis Adams.

Works: Ford. See Jefferson, Thomas. Works. Federal Edition. Edited by Paul Leicester Ford.

Works: Hamilton. See Hamilton, Alexander. Works. Edited by John C. Hamilton.

Works: Lodge. See Hamilton, Alexander. Works. Federal Edition. Edited by Henry Cabot Lodge.[Pg xxvi]

Writings: Conway. See Paine, Thomas. Writings. Edited by Moncure Daniel Conway.

Writings: Ford. See Washington, George. Writings. Edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford.

Writings: Hunt. See Madison, James. Writings. Edited by Gaillard Hunt.

Writings: Smyth. See Franklin, Benjamin. Writings. Edited by Albert Henry Smyth.

Writings: Sparks. See Washington, George. Writings. Edited by Jared Sparks.

THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL

THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL

CHAPTER I

ANCESTRY AND ENVIRONMENT

Often do the spirits of great events stride on before the events and in to-day already walks to-morrow. (Schiller.)

I was born an American; I will live an American; I shall die an American. (Webster.)

"The British are beaten! The British are beaten!" From cabin to cabin, from settlement to settlement crept, through the slow distances, this report of terror. The astounding news that Braddock was defeated finally reached the big plantations on the tidewater, and then spread dismay and astonishment throughout the colonies.

The painted warriors and the uniformed soldiers of the French-Indian alliance had been growing bolder and bolder, their ravages ever more daring and bloody.[1] Already the fear of them had checked the thin wave of pioneer advance; and it seemed to the settlers that their hereditary enemies from across the water might succeed in confining British dominion in America to the narrow strip between the ocean and the mountains. For the royal colonial authorities had not been able to cope with their foes.[2]

[Pg 2]But there was always the reserve power of Great Britain to defend her possessions. If only the home Government would send an army of British veterans, the colonists felt that, as a matter of course, the French and Indians would be routed, the immigrants made safe, and the way cleared for their ever-swelling thousands to take up and people the lands beyond the Alleghanies.

So when at last, in 1755, the redoubtable Braddock and his red-coated regiments landed in Virginia, they were hailed as deliverers. There would be an end, everybody said, to the reign of terror which the atrocities of the French and Indians had created all along the border. For were not the British grenadiers invincible? Was not Edward Braddock an experienced commander, whose bravery was the toast of his fellow officers?[3] So the colonists had been told, and so they believed.

They forgave the rudeness of their British champions; and Braddock marched away into the wilderness carrying with him the unquestioning confidence of the people.[4] It was hardly thought necessary for any Virginia fighting men to accompany him; and that haughty, passionate young Virginia soldier, George Washington (then only twenty-three years of age, but already the chief military figure of the Old Dominion), and his Virginia rangers were invited to[Pg 3] accompany Braddock more because they knew the country better than for any real aid in battle that was expected of them. "I have been importuned," testifies Washington, "to make this campaign by General Braddock, ... conceiving ... that the ... knowledge I have ... of the country, Indians, &c. ... might be useful to him."[5]

So through the ancient and unbroken forests Braddock made his slow and painful way.[6] Weeks passed; then months.[7] But there was no impatience, because everybody knew what would happen when his scarlet columns should finally meet and throw themselves upon the enemy. Yet this meeting, when it came, proved to be one of the lesser tragedies of history, and had a deep and fateful effect upon American public opinion and upon the life and future of the American people.[8]

Time has not dulled the vivid picture of that disaster. The golden sunshine of that July day; the pleasant murmur of the waters of the Monongahela; the silent and somber forests; the steady tramp,[Pg 4] tramp of the British to the inspiriting music of their regimental bands playing the martial airs of England; the bright uniforms of the advancing columns giving to the background of stream and forest a touch of splendor; and then the ambush and surprise; the war-whoops of savage foes that could not be seen; the hail of invisible death, no pellet of which went astray; the pathetic volleys which the doomed British troops fired at hidden antagonists; the panic; the rout; the pursuit; the slaughter; the crushing, humiliating defeat![9]

Most of the British officers were killed or wounded as they vainly tried to halt the stampede.[10] Braddock himself received a mortal hurt.[11] Raging with battle lust, furious at what he felt was the stupidity and cowardice of the British regulars,[12] the youthful Washington rode among the fear-frenzied Englishmen, striving to save the day. Two horses were shot under him. Four bullets rent his uniform.[13] But, crazed with fright, the Royal soldiers were beyond human control.

Only the Virginia rangers kept their heads and their courage. Obeying the shouted orders of their young commander, they threw themselves between the terror-stricken British and the savage victors;[Pg 5] and, fighting behind trees and rocks, were an ever-moving rampart of fire that saved the flying remnants of the English troops. But for Washington and his rangers, Braddock's whole force would have been annihilated.[14] Colonel Dunbar and his fifteen hundred British regulars, who had been left a short distance behind as a reserve, made off to Philadelphia as fast as their panic-winged feet could carry them.[15]

So everywhere went up the cry, "The British are beaten!" At first rumor had it that the whole force was destroyed, and that Washington had been killed in action.[16] But soon another word followed hard upon this error—the word that the boyish Virginia captain and his rangers had fought with coolness, skill, and courage; that they alone had prevented the extinction of the British regulars; that they alone had come out of the conflict with honor and glory.

Thus it was that the American colonists suddenly came to think that they themselves must be their own defenders. It was a revelation, all the more impressive because it was so abrupt, unexpected, and dramatic, that the red-coated professional soldiers were not the unconquerable warriors the colonists[Pg 6] had been told that they were.[17] From colonial "mansion" to log cabin, from the provincial "capitals" to the mean and exposed frontier settlements, Braddock's defeat sowed the seed of the idea that Americans must depend upon themselves.[18]

As Bacon's Rebellion at Jamestown, exactly one hundred years before Independence was declared at Philadelphia, was the beginning of the American Revolution in its first clear expression of popular rights,[19] so Braddock's defeat was the inception of that same epoch in its lesson of American military self-dependence.[20] Down to Concord and Lexington, Great Bridge and Bunker Hill, the overthrow of the King's troops on the Monongahela in 1755 was a theme of common talk among men, a household legend on which American mothers brought up their children.[21]

Close upon the heels of this epoch-making event, John Marshall came into the world. He was born in[Pg 7] a little log cabin in the southern part of what now is Fauquier County, Virginia (then a part of Prince William), on September 24, 1755,[22] eleven weeks after Braddock's defeat. The Marshall cabin stood about a mile and a half from a cluster of a dozen similar log structures built by a handful of German families whom Governor Spotswood had brought over to work his mines. This little settlement was known as Germantown, and was practically on the frontier.[23]

Thomas Marshall, the father of John Marshall, was a close friend of Washington, whom he ardently admired. They were born in the same county, and their acquaintance had begun, apparently, in their boyhood.[24] Also, as will presently appear, Thomas Marshall had for about three years been the companion of Washington, when acting as his assistant in surveying the western part of the Fairfax estate.[25] From that time forward his attachment to Washington amounted to devotion.[26]

Also, he was, like Washington, a fighting man.[27] It seems strange, therefore, that he did not accom[Pg 8]pany his hero in the Braddock expedition. There is, indeed, a legend that he did go part of the way.[28] But this, like so many stories concerning him, is untrue.[29] The careful roster, made by Washington of those under his command,[30] does not contain the name of Thomas Marshall either as officer or private. Because of their intimate association it is certain that Washington would not have overlooked him if he had been a member of that historic body of men.

So, while the father of John Marshall was not with his friend and leader at Braddock's defeat, no man watched that expedition with more care, awaited its outcome with keener anxiety, or was more affected by the news, than Thomas Marshall. Beneath no rooftree in all the colonies, except, perhaps, that of Washington's brother, could this capital event have made a deeper impression than in the tiny log house in the forests of Prince William County, where John Marshall, a few weeks afterwards, first saw the light of day.

Wars and rumors of wars, ever threatening danger, and stern, strong, quiet preparation to meet whatever befell—these made up the moral and intellectual atmosphere that surrounded the Marshall cabin before and after the coming of Thomas and Mary[Pg 9] Marshall's first son. The earliest stories told this child of the frontier[31] must have been those of daring and sacrifice and the prevailing that comes of them.

Almost from the home-made cradle John Marshall was taught the idea of American solidarity. Braddock's defeat, the most dramatic military event before the Revolution,[32] was, as we have seen, the theme of fireside talk; and from this grew, in time, the conviction that Americans, if united,[33] could not only protect their homes from the savages and the French, but defeat, if need be, the British themselves.[34] So thought the Marshalls, father and mother; and so they taught their children, as subsequent events show.

It was a remarkable parentage that produced this child who in manhood was to become the master-builder of American Nationality. Curiously enough, it was exactly the same mingling of human elements that gave to the country that great apostle of the rights of man, Thomas Jefferson. Indeed, Jefferson's mother and Marshall's grandmother were first cousins. The mother of Thomas Jefferson was Jane[Pg 10] Randolph, daughter of Isham Randolph of Turkey Island; and the mother of John Marshall was Mary Randolph Keith, the daughter of Mary Isham Randolph, whose father was Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe, the brother of Jefferson's maternal grandfather.

Thus, Thomas Jefferson was the great-grandson and John Marshall the great-great-grandson of William Randolph and Mary Isham. Perhaps no other couple in American history is so remarkable for the number of distinguished descendants. Not only were they the ancestors of Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall, but also of "Light Horse Harry" Lee, of Revolutionary fame, Edmund Randolph, Washington's first Attorney-General, John Randolph of Roanoke, George Randolph, Secretary of War under the Confederate Government, and General Robert E. Lee, the great Southern military leader of the Civil War.[35]

COLONEL WILLIAM RANDOLPH

COLONEL WILLIAM RANDOLPH

MARY ISHAM RANDOLPH

MARY ISHAM RANDOLPH

The Virginia Randolphs were one of the families of that proud colony who were of undoubted gentle descent, their line running clear and unbroken at least as far back as 1550. The Ishams were a somewhat older family, their lineage being well established to 1424. While knighthood was conferred upon one ancestor of Mary Isham, the Randolph and Isham families were of the same social stratum, both being of the English gentry.[36] The Virginia Randolphs [Pg 11] were brilliant in mind, physically courageous, commanding in character, generally handsome in person, yet often as erratic as they were gifted.

When the gentle Randolph-Isham blood mingled with the sturdier currents of the common people, the result was a human product stronger, steadier, and abler than either. So, when Jane Randolph became the wife of Peter Jefferson, a man from the grass roots, the result was Thomas Jefferson. The union of a daughter of Mary Randolph with Thomas Marshall, a man of the soil and forests, produced John Marshall.[37]

Physically and mentally, Peter Jefferson and Thomas Marshall were much alike. Both were powerful men of great stature. Both were endowed with rare intellectuality.[38] Both were hard-working, provident, and fearless. Even their occupations were the same: both were land surveyors. The chief difference between them was that, whereas Peter Jefferson appears to have been a hearty and con[Pg 12]vivial person,[39] Thomas Marshall seems to have been self-contained though adventurous, and of rather austere habits. Each became the leading man of his county[40] and both were chosen members of the House of Burgesses.[41]

On the paternal side, it is impossible to trace the origin of either Peter Jefferson[42] or Thomas Marshall farther back than their respective great-grandfathers, without floundering, unavailingly, in genealogical quicksands.

Thomas Marshall was the son of a very small planter in Westmoreland County, Virginia. October 23, 1727, three years before Thomas was born, his father, John Marshall "of the forest," acquired by deed, from William Marshall of King and Queen County, two hundred acres of poor, low, marshy land located on Appomattox Creek.[43] Little as the value of land in Virginia then was, and continued to be for three quarters of a century afterwards,[44] this particu[Pg 13]lar tract seems to have been of an especially inferior quality. The deed states that it is a part of twelve hundred acres which had been granted to "Jno. Washington & Thos. Pope, gents ... & by them lost for want of seating."

Here John Marshall "of the forest"[45] lived until his death in 1752, and here on April 2, 1730, Thomas Marshall was born. During the quarter of a century that this John Marshall remained on his little farm, he had become possessed of several slaves, mostly, perhaps, by natural increase. By his will he bequeaths to his ten children and to his wife six negro men and women, ten negro boys and girls, and two negro children. In addition to "one negro fellow named Joe and one negro woman named Cate" he gives to his wife "one Gray mair named beauty and side saddle also six hogs also I leave her the use of my land During her widowhood, and afterwards to fall to my son Thomas Marshall and his heirs forever."[46] One year later the widow, Elizabeth Marshall, deeded half of this two hundred acres to her son Thomas Marshall.[47]

[Pg 14]Such was the environment of Thomas Marshall's birth, such the property, family, and station in life of his father. Beyond these facts, nothing positively is known of the ancestry of John Marshall on his father's side. Marshall himself traces it no further back than his grandfather. "My Father, Thomas Marshall, was the eldest son of John Marshall, who intermarried with a Miss Markham and whose parents migrated from Wales, and settled in the county of Westmoreland, in Virginia, where my Father was born."[48]

It is probable, however, that Marshall's paternal great-grandfather was a carpenter of Westmoreland County. A Thomas Marshall, "carpenter," as he describes himself in his will, died in that county in 1704. He devised his land to his son William. A William Marshall of King and Queen County deeded to John Marshall "of the forest," for five shillings, the two hundred acres of land in Westmoreland County, as above stated.[49] The fair inference is that this William was the elder brother of John "of the forest" and that both were sons of Thomas the "carpenter."

THOMAS MARSHALL

THOMAS MARSHALL

Beyond his paternal grandfather or at furthest his great-grandfather, therefore, the ancestry of John Marshall, on his father's side, is lost in the fogs of uncertainty.[50] It is only positively known that [Pg 15] his grandfather was of the common people and of moderate means.[51]

Concerning his paternal grandmother, nothing definitely is established except that she was Elizabeth Markham, daughter of Lewis Markham, once Sheriff of Westmoreland County.[52]

John Marshall's lineage on his mother's side, however, is long, high, and free from doubt, not only through the Randolphs and Ishams, as we have seen, but through the Keiths. For his maternal grand[Pg 17]father was an Episcopal clergyman, James Keith, of the historic Scottish family of that name, who were hereditary Earls Marischal of Scotland. The Keiths had been soldiers for generations, some of them winning great renown.[53] One of them was James Keith, the Prussian field marshal and ablest of the officers of Frederick the Great.[54] James Keith, a younger son of this distinguished family, was destined for the Church;[55] but the martial blood flowing in his veins asserted itself and, in his youth, he also became a soldier, upholding with arms the cause of the Pretender. When that rebellion was crushed, he fled to Virginia, resumed his sacred calling, returned to England for orders, came back to Virginia[56] and during his remaining years performed his priestly duties with rare zeal and devotion.[57] The motto of the Keiths of Scotland was "Veritas Vincit," and John Marshall adopted it. During most of his life he wore an amethyst with the ancient Keith motto engraved upon it.[58]

When past middle life the Scottish parson married Mary Isham Randolph,[59] granddaughter of William Randolph and Mary Isham. In 1754 their[Pg 18] daughter, Mary Randolph Keith, married Thomas Marshall and became the mother of John Marshall. "My mother was named Mary Keith, she was the daughter of a clergyman, of the name of Keith, who migrated from Scotland and intermarried with a Miss Randolph of James River" is Marshall's comment on his maternal ancestry.[60]

Not only was John Marshall's mother uncommonly well born, but she was more carefully educated than most Virginia women of that period.[61] Her father received in Aberdeen the precise and methodical training of a Scottish college;[62] and, as all parsons in the Virginia of that time were teachers, it is certain that he carefully instructed his daughter. He was a deeply religious man, especially in his latter years,—so much so, indeed, that there was in him a touch of mysticism; and the two marked qualities of his daughter, Mary, were deep piety and strong intellectuality. She had, too, all the physical hardiness of her Scottish ancestry, fortified by the active and useful labor which all Virginia women of her class at that time performed.

MARY RANDOLPH KEITH MARSHALL

MARY RANDOLPH KEITH MARSHALL

(Mrs. Thomas Marshall)

So Thomas Marshall and Mary Keith combined unusual qualities for the founding of a family. Great strength of mind both had, and powerful wills; and through the veins of both poured the blood of daring. Both were studious-minded, too, and husband and wife alike were seized of a passion for self-improvement as well as a determination to better their circumstances. It appears that Thomas Marshall was by nature religiously inclined;[63] and this made all the greater harmony between himself and his wife. The physical basis of both husband and wife seems to have been well-nigh perfect.

Fifteen children were the result of this union, every one of whom lived to maturity and almost all of whom rounded out a ripe old age. Every one of them led an honorable and successful life. Nearly all strongly impressed themselves upon the community in which they lived.

It was a peculiar society of which this prolific and virile family formed a part, and its surroundings were as strange as the society itself. Nearly all of Virginia at that time was wilderness,[64] if we look upon it with the eyes of to-day. The cultivated parts were given over almost entirely to the raising of tobacco, which soon drew from the soil its virgin strength; and the land thus exhausted usually was abandoned to the forest, which again soon covered it. No use was made of the commonest and most[Pg 20] obvious fertilizing materials and methods; new spaces were simply cleared.[65] Thus came a happy-go-lucky improvidence of habits and character.

This shiftlessness was encouraged by the vast extent of unused and unoccupied domain. Land was so cheap that riches measured by that basis of all wealth had to be counted in terms of thousands and tens of thousands of acres.[66] Slavery was an even more powerful force making for a kind of lofty disdain of physical toil among the white[Pg 21] people.[67] Black slaves were almost as numerous as white free men.[68] On the great plantations the negro quarters assumed the proportions of villages;[69] and the masters of these extensive holdings were by example the arbiters of habits and manners to the whole social and industrial life of the colony. While an occasional great planter was methodical and industrious,[70] careful and systematic methods were rare. Manual labor was, to most of these lords of circumstance, not only unnecessary but degrading. To do no physical work that could be avoided on the one hand, and on the other hand, to own as many slaves as possible, was, generally, the ideal of members of the first estate.[71] This spread to the classes below, until it became a common ambition of white men throughout the Old Dominion.

While contemporary travelers are unanimous upon this peculiar aspect of social and economic conditions in old Virginia, the vivid picture drawn by Thomas Jefferson is still more convincing. "The whole com[Pg 22]merce between master and slave," writes Jefferson, "is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this and learn to imitate it.... Thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny ... the man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved.... With the morals of the people their industry also is destroyed. For in a warm climate, no man will labour for himself who can make another labour for him.... Of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labour."[72]

Two years after he wrote his "Notes on Virginia" Jefferson emphasized his estimate of Virginia society. "I have thought them [Virginians] as you found them," he writes Chastellux, "aristocratical, pompous, clannish, indolent, hospitable ... careless of their interests, ... thoughtless in their expenses and in all their transactions of business." He again ascribes many of these characteristics to "that warmth of their climate which unnerves and unmans both body and mind."[73]

From this soil sprang a growth of habits as noxious as it was luxuriant. Amusements to break the monotony of unemployed daily existence took the form of horse-racing, cock-fighting, and gambling.[74] [Pg 23] Drinking and all attendant dissipations were universal and extreme;[75] this, however, was the case in all the colonies.[76] Bishop Meade tells us that even the clergy indulged in the prevailing customs to the neglect of their sacred calling; and the church itself was all but abandoned in the disrepute which the conduct of its ministers brought upon the house of God.[77]

[Pg 24]Yet the higher classes of colonial Virginians were keen for the education of their children, or at least of their male offspring.[78] The sons of the wealthiest planters often were sent to England or Scotland to be educated, and these, not infrequently, became graduates of Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh.[79] Others of this class were instructed by private tutors.[80] Also a sort of scanty and fugitive public instruction was given in rude cabins, generally located in abandoned fields. These were called the Old Field Schools.[81]

More than forty per cent of the men who made deeds or served on juries could not sign their names, although they were of the land-owning and better educated classes;[82] the literacy of the masses, especially that of the women,[83] was, of course, much lower.

An eager desire, among the "quality," for reading brought a considerable number of books to the homes of those who could afford that luxury.[84] A few[Pg 25] libraries were of respectable size and two or three were very large. Robert Carter had over fifteen hundred volumes,[85] many of which were in Latin and Greek, and some in French.[86] William Byrd collected at Westover more than four thousand books in half a dozen languages.[87] But the Carter and Byrd libraries were, of course, exceptions. Byrd's library was the greatest, not only in Virginia, but in all the colonies, except that of John Adams, which was equally extensive and varied.[88]

Doubtless the leisure and wealth of the gentry, created by the peculiar economic conditions of the Old Dominion, sharpened this appetite for literature and afforded to the wealthy time and material for the gratification of it. The passion for reading and discussion persisted, and became as notable a characteristic of Virginians as was their dislike for physical labor, their excessive drinking, and their love of strenuous sport and rough diversion.

There were three social orders or strata, all contemporary observers agree, into which Virginians were divided; but they merged into one another so that the exact dividing line was not clear.[89] First, of course, came the aristocracy of the immense plantations. While the social and political dominance of this class was based on wealth, yet some of its members were derived from the English gentry, with, perhaps, an occasional one from a noble family in the[Pg 26] mother country.[90] Many, however, were English merchants or their sons.[91] It appears, also, that the boldest and thriftiest of the early Virginia settlers, whom the British Government exiled for political offenses, acquired extensive possessions, became large slave-owners, and men of importance and position. So did some who were indentured servants;[92] and, indeed, an occasional transported convict rose to prominence.[93]

But the genuine though small aristocratic element gave tone and color to colonial Virginia society. All, except the "poor whites," looked to this supreme group for ideals and for standards of manners and conduct. "People of fortune ... are the pattern of all behaviour here," testifies Fithian of New Jersey, tutor in the Carter household.[94] Also, it was, of course, the natural ambition of wealthy planters and those who expected to become such to imitate the life of the English higher classes. This was much truer in Virginia than in any other colony; for she had been more faithful to the Crown and to the[Pg 27] royal ideal than had her sisters. Thus it was that the Old Dominion developed a distinctively aristocratic and chivalrous social atmosphere peculiar to herself,[95] as Jefferson testifies.

Next to the dominant class came the lesser planters. These corresponded to the yeomanry of the mother country; and most of them were from the English trading classes.[96] They owned little holdings of land from a few hundred to a thousand and even two thousand acres; and each of these inconsiderable landlords acquired a few slaves in proportion to his limited estate. It is possible that a scanty number of this middle class were as well born as the best born of the little nucleus of the genuine aristocracy; these were the younger sons of great English houses to whom the law of primogeniture denied equal opportunity in life with the elder brother. So it came to pass that the upper reaches of the second estate in the social and industrial Virginia of that time merged into the highest class.

At the bottom of the scale, of course, came the poverty-stricken whites. In eastern Virginia this was the class known as the "poor whites"; and it was more distinct than either of the two classes above it. These "poor whites" lived in squalor, and without the aspirations or virtues of the superior orders. They carried to the extreme the examples of[Pg 28] idleness given them by those in higher station, and coarsened their vices to the point of brutality.[97] Near this social stratum, though not a part of it, were classed the upland settlers, who were poor people, but highly self-respecting and of sturdy stock.

Into this structure of Virginia society Fate began to weave a new and alien thread about the time that Thomas Marshall took his young bride to the log cabin in the woods of Prince William County where their first child was born. In the back country bordering the mountains appeared the scattered huts of the pioneers. The strong character of this element of Virginia's population is well known, and its coming profoundly influenced for generations the political, social, industrial, and military history of that section. They were jealous of their "rights," impatient of restraint, wherever they felt it, and this was seldom. Indeed, the solitariness of their lives, and the utter self-dependence which this forced upon them, made them none too tolerant of law in any form.

These outpost settlers furnished most of that class so well known to our history by the term "backwoodsmen," and yet so little understood. For the heroism, the sacrifice, and the suffering of this "advance guard of civilization" have been pictured[Pg 29] by laudatory writers to the exclusion of its other and less admirable qualities. Yet it was these latter characteristics that played so important a part in that critical period of our history between the surrender of the British at Yorktown and the adoption of the Constitution, and in that still more fateful time when the success of the great experiment of making out of an inchoate democracy a strong, orderly, independent, and self-respecting nation was in the balance.

These American backwoodsmen, as described by contemporary writers who studied them personally, pushed beyond the inhabited districts to get land and make homes more easily. This was their underlying purpose; but a fierce individualism, impatient even of those light and vague social restraints which the existence of near-by neighbors creates, was a sharper spur.[98] Through both of these motives, too, ran the spirit of mingled lawlessness and adventure. The physical surroundings of the backwoodsman nourished the non-social elements of his character. The log cabin built, the surrounding patch of clearing made, the seed planted for a crop of cereals only large enough to supply the household needs—these almost ended the backwoodsman's agricultural activities and the habits of regular industry which farming requires.

While his meager crops were coming on, the backwoodsman must supply his family with food from the stream and forest. The Indians had not yet retreated so far, nor were their atrocities so remote,[Pg 30] that fear of them had ceased;[99] and the eye of the backwoodsman was ever keen for a savage human foe as well as for wild animals. Thus he became a man of the rifle,[100] a creature of the forests, a dweller amid great silences, self-reliant, suspicious, non-social, and almost as savage as his surroundings.[101]

But among them sometimes appeared families which sternly held to high purposes, orderly habits, and methodical industry;[102] and which clung to moral and religious ideals and practices with greater tenacity than ever, because of the very difficulties of their situation. These chosen families naturally became the backbone of the frontier; and from them came the strong men of the advanced settlements.[Pg 31]

Such a figure among the backwoodsmen was Thomas Marshall. Himself a product of the settlements on the tidewater, he yet was the personification of that spirit of American advance and enterprise which led this son of the Potomac lowlands ever and ever westward until he ended his days in the heart of Kentucky hundreds of miles through the savage wilderness from the spot where, as a young man, he built his first cabin home.

This, then, was the strange mingling of human elements that made up Virginia society during the middle decades of the eighteenth century—a society peculiar to the Old Dominion and unlike that of any other place or time. For the most part, it was idle and dissipated, yet also hospitable and spirited, and, among the upper classes, keenly intelligent and generously educated. When we read of the heavy drinking of whiskey, brandy, rum, and heady wine; of the general indolence, broken chiefly by fox-hunting and horse-racing, among the quality; of the coarser sport of cock-fighting shared in common by landed gentry and those of baser condition, and of the eagerness for physical encounter which seems to have pervaded the whole white population,[103] we wonder at the greatness of mind and soul which grew from such a social soil.

Yet out of it sprang a group of men who for ability, character, spirit, and purpose, are not outshone and have no precise counterpart in any other company of illustrious characters appearing in like space of time[Pg 32] and similar extent of territory. At almost the same point of time, historically speaking,—within thirty years, to be exact,—and on the same spot, geographically speaking,—within a radius of a hundred miles,—George Mason, James Madison, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and George Washington were born. The life stories of these men largely make up the history of their country while they lived; and it was chiefly their words and works, their thought and purposes, that gave form and direction, on American soil, to those political and social forces which are still working out the destiny of the American people.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] For instance, the Indians massacred nine families in Frederick County, just over the Blue Ridge from Fauquier, in June, 1755. (Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, July 24, 1755.)

[2] Marshall, i, 12-13; Campbell, 469-71. "The Colonial contingents were not nearly sufficient either in quantity or quality." (Wood, 40.)

[3] Braddock had won promotion solely by gallantry in the famous Coldstream Guards, the model and pride of the British army, at a time when a lieutenant-colonelcy in that crack regiment sold for £5000 sterling. (Lowdermilk, 97.)

[4] "The British troops had been looked upon as invincible, and preparations had been made in Philadelphia for the celebration of Braddock's anticipated victory." (Ib., 186.)

[5] Washington to Robinson, April 20, 1755; Writings: Ford, i, 147.

[6] The "wild desert country lying between fort Cumberland and fort Frederick [now the cities of Cumberland and Frederick in Maryland], the most common track of the Indians, in making their incursions into Virginia." (Address in the Maryland House of Delegates, 1757, as quoted by Lowdermilk, 229-30.) Cumberland was "about 56 miles beyond our [Maryland] settlements." (Ib.) Cumberland "is far remote from any of our inhabitants." (Washington to Dinwiddie, Sept. 23, 1756; Writings: Ford, i, 346.) "Will's Creek was on the very outskirts of civilization. The country beyond was an unbroken and almost pathless wilderness." (Lowdermilk, 50.)

[7] It took Braddock three weeks to march from Alexandria to Cumberland. He was two months and nineteen days on the way from Alexandria to the place of his defeat. (Ib., 138.)

[8] "All America watched his [Braddock's] advance." (Wood, 61.)

[9] For best accounts of Braddock's defeat see Bradley, 75-107; Lowdermilk, 156-63; and Marshall, i, 7-10.

[10] "Of one hundred and sixty officers, only six escaped." (Lowdermilk, footnote to 175.)

[11] Braddock had five horses killed under him. (Ib., 161.)

[12] "The dastardly behavior of the Regular [British] troops," who "broke and ran as sheep before hounds." (Washington to Dinwiddie, July 18, 1755; Writings: Ford, i, 173-74.)