“Peanut.” Illustrated. 16mo net $ .50

Mark Twain: A Biography. Illustrated.

Octavo, Uniform Red Cloth, Trade Edition, 3 Vols. (in a box) net $6.00

Octavo, Cloth, Full Gilt Backs, Gilt Tops, Library Edition, 3 Vols. (in a box) net 7.00

Octavo, Three-quarter Calf, Gilt Tops, 3 Vols. (in a box) net 14.50

Octavo, Three-quarter Levant, Gilt Tops, 3 Vols. (in a box) net 15.50

The Ship Dwellers. Illustrated. 8vo net 1.50

The Tent-Dwellers. Illustrated. Post 8vo 1.50

The Hollow Tree Snowed-In Book. Ill’d. Crown 8vo 1.50

The Hollow Tree and Deep Woods Book. Illustrated. Post 8vo 1.50

From Van-Dweller to Commuter. Illustrated. Post 8vo 1.50

Life of Thomas Nast. Illustrated. 8vo net 5.00

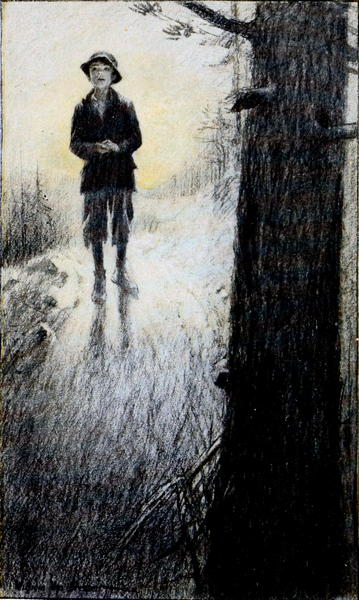

Frontispiece: Peanut

“PEANUT”

I

THE blackened stumps had been left—perhaps more easily to identify the little clearing about the grave. From the ravine below, where the stage passed, they were still visible, but the two-inch headboard, weather-beaten by a year of sun and rain, was getting lost in a growth of bushes. When pointed out by the driver as marking the “last hangout of Blazer Sam,” who had “died with his boots on, and had two cuss-words in his epitaph,” it could be discerned now with difficulty and there were travelers, men mostly, who prevailed upon the somewhat garrulous official to “let the horses blow a little while” they scaled the mountain for a closer view. The epitaph itself was worth the climb.

A few of those who had made the steep ascent for that literary treat, and to pay their respects to the grave of the notorious desperado, highwayman, and general outlaw, had seen something dart away into the bushes at their approach. As a rule, they had been too far off to tell whether it was a coyote, a jack-rabbit, or a boy. Those who had obtained the closer view usually agreed that it was a boy—a very thin boy of about ten, with pale hair and no head-covering.

The stage-driver in due time acquired information. Those who had said it was a boy were correct. When Blazer Sam had made his final exit in the abrupt manner noted, and so taken his boots with him, he had left behind the Rose of Texas, acquired long before in a poker game, and a little waif known as Peanut, picked up like a stray kitten during one of the Blazer’s devious wanderings. The name Peanut might have come from the color of his hair, or from his small size and value. The driver did not know. He had heard that the boy had been kindly treated by both the Blazer and the Rose, and with the latter still occupied Sam’s little hut in the woods above the clearing. The waif probably came out into the opening to see the stage pass. Then again he might be “kinder lonesome for Sam.”

The driver was right in at least one of these conjectures. Peanut was indeed “lonesome for Sam.” He could remember very little preceding the day six years before when Sam had brought him home to be company for the Rose, during absences that had grown ever more prolonged as the years passed and the outlaw’s field of labor had been found farther and yet farther away from his cabin on the hillside. What Peanut did remember was that he never had been hungry since that day. Also, the times when Sam had come home. For whatever had been the source of Sam’s gains, he had provided well for the Rose; and if, as was said, the hand of every man was against him and his hand against every man you could not have guessed it to see the small, lean hand of Peanut locked closely in his own, and the two wandering over the mountain together in those days that were now no more and would never more return. There remained to Peanut only their memory and the barren comfort of a grave and an epitaph.

Yet these were much to the lonely child. When he had pushed through the bushes to the grave he felt close to Sam, while the vigor of the epitaph, which he could read, because this much the Rose had taught him, was somehow satisfying. The last line afforded him special comfort. It assured him that no one would ever dare to take Sam away.

It did not occur to him that there was anything objectionable in the lines. He did not know that epitaphs are not so true, as a rule; while as for the emphasis, it was of the sort he knew best. That he did not use those words himself was only for the same reason that he did not chew tobacco yet, or drink whisky. He had been assured by the Rose that these luxuries were not for little boys, and he had been willing to wait. He was glad, however, that Sam, who had indulged liberally in the good things of life, could still have the best on his tombstone.

Portions of the inscription puzzled him. He did not know that there had been a price on the outlaw’s head, and he wondered why the “greaser,” referred to in line three, should want to kill Sam. Neither did he realize that line two doubtless alluded to the Blazer’s slight valuation of life in general, rather than to any disregard of his own particular existence. Peanut failed to understand why it was that Sam had not cared for life when by living he could come home now and then and show him the trout brook, and make whistles for him, and visit the eagle’s nest in the cliff. Why, once they had even found a cave, and in it a shot and dying mother bear, with two little bears, that were now big bears and still came to the cabin to be fed. When it rained they had sometimes run for this cave, to build a fire at the mouth of it and to lie there and watch the blaze and talk and play with the bears until the rain was over. What was the reason, then, that Sam had not cared to live and have all these things when he, Peanut, had cared for them so much?

He cared for them still. He could find his way to the brook and the eagle’s nest, and to the cave where the bears were always glad to see him, especially when he brought food. The innumerable squirrels and birds and other wood-folk were his own; yet from them all he turned each day to Sam’s grave, there to live over again those other days when Sam had taught him the lore and kinship of the mountains, and when, hand in hand, they had pushed through vines and leaves to visit the forest people together.

Often when it was bright and warm he stayed by the grave most of the day, and sometimes, with his face down in the grass, he would talk to Sam. When it stormed he crept under the bushes and felt a deep commiseration for the lonely mound with the rain pelting down upon it. There had been times in winter, when the snow was deepest, that he could not go at all. On these days he moped in the house with the Rose, who since Sam’s death had supplied their meager wants by doing mending and an occasional washing for the mining-camp below. She had grown rather fat and silent and spent most of her days playing solitaire and telling her own fortune with a greasy pack of cards, which diversions did not appeal to Peanut.

But in supposing that Peanut had come out into the clearing to see the stage pass, the driver had been wholly wrong. Sam had never cared for the stage or for people. In fact, he had rather avoided those things, Peanut thought, and he knew Sam always had good reasons for what he did. When the boy saw strangers climbing the steep hill to visit the grave he fled hastily into the bushes, where, lying hid, he watched to see that they did not carry anything away save perhaps an occasional walking-stick or a handful of goldenrod. When they laughed and talked loudly he was fiercely angry, and thought he understood why it was that Sam had preferred the society of the quiet wood-folk.

With those of his own age Peanut had had but one experience. Twice the Rose had prevailed upon him to go with her to the mining-camp, and on the last of these occasions a boy—the only one in the camp—had defrauded him of his best whistle and of such other valuables as had been upon his person at the time. He had received in exchange some yellow ore, which the boy had insisted was gold, but which the Rose declared to be slag, and worthless. It was his first experience with deception.

Peanut had refused to go to the camp again.

II

ONE day in late August the stage stopped to let a woman climb the hill. Women visited the grave now and then, and Miss Cynthia Schofield, age thirty-four, a teacher in a Chicago public institution of learning, was just the one to improve such an opportunity. For Miss Schofield was progressive in the matter of acquiring knowledge. She spent each summer in some elemental region, of which she made numerous photographs and notes. These she used later in certain illustrated evening lectures called “In-gatherings,” given by Miss Schofield for the benefit of persons with fewer opportunities; also for the purpose of adding a trifle to her own modest income. She was “doing the mines” this year, and her present destination was the camp, two miles farther down. The desperado’s grave and history would make a picturesque addition to her collection.

The climb was harder than it appeared from below. Being the only passenger, the driver had told her to take her time, and more than once she leaned against a boulder to look down into the dark ravine made famous by some of Blazer’s earlier exploits. She recognized the artistic value of the fact that his last resting-place overlooked the scene of his former depredations. She must certainly bring this out well in her lecture, and as she toiled upward she was forming in her mind certain phrases, with a view to this result. Then she pushed gently between two small cedars into the opening where the grave was.

At first glance she saw only some bushes and fireweed about the blackened stumps, and the riotous mass of goldenrod which possessed one corner of the little clearing. Then just by the goldenrod she saw the grave, and paused, for, face down upon it, asleep, lay a meager barefoot boy with faded hair.

Miss Schofield was, first of all, the artist. She had anticipated nothing so rich in value as this, and with deft hands she adjusted the camera and secured the range. There came a sharp click, and the outlaw’s grave, the goldenrod, the fireweed, the black stumps, and the faded sleeping boy had been added to her store of choice in-gatherings.

There had been still another result. The snap of the shutter had brought the light figure to its feet, like some spry wood creature as suddenly disturbed. An instant more and he would have darted away into the bushes; only, Miss Schofield spoke just then, and with persuasiveness—the result of long pedagogical training.

“Don’t go! Oh, please don’t!” she pleaded, gently. “Please wait. I want so much to speak to you.”

Peanut had no particular reason for being afraid of women. The only one he had studied at close range had been kind to him to the point of indulgence. There was something in the voice of this one that held him fast. The woman came a step closer. She seemed young and beautiful to Peanut.

“Please tell me your name,” she said.

“Peanut.”

“Oh, that is what they call you, perhaps. Your real name, I mean.”

The boy made no reply at first to this comment. He seemed gathering something from the mists of memory.

“Sam told me that it used to be—longer than that,” he ventured at last, very slowly. “He told me once that it was Philip—Nutt, but he said P. was the same as Philip, and that he thought Peanut fit me better.”

Panic seemed about to return, as the result of this long speech, and once more it required the soothing diplomacy of Miss Schofield to detain him.

“How very nice,” she said. “And now won’t you please tell me where you live, and about Sam and the grave?”

Again Peanut hesitated. Then he pointed behind him.

“I live up there; and Sam, he—why he’s in the grave, and dam the man that moves his bones.”

Miss Schofield had been unprepared for this. Her emotion, however, was mistaken by Peanut for incredulity. “I can show it to you on the board,” he insisted, eagerly.

The woman came up close, now, and followed where his wisp of a finger pointed. As he indicated each line, he repeated it with a sort of monotonous tenderness, laying special emphasis on the last.

Miss Schofield’s look of concern became one of sympathetic understanding. The waif turned to her.

“You didn’t want to take Sam away, anyhow, did you?”

“Oh, no indeed! I don’t want to take any one away—” She hesitated and looked down into the wistful face before her. “At least, not Sam,” she qualified. “I have already taken a picture of the grave and you shall have one of them. Tell me, Philip, whom you live with, so I shall know how to send it.”

The sound of his name thus spoken may have awakened a sort of dignity in the waif.

“I live with the Rose of Texas,” he said, gravely. “Me an’ Sam both did, till Sam was plugged by a greaser unbeknowns, and—”

Miss Schofield interrupted rather hastily.

“Never mind the next line, Philip. I remember it. Just a moment—”

She had taken out her note-book and was puzzling over the proper entry. “Philip Nutt, alias Peanut, Care of the Rose of Texas, former housekeeper for Blazer Sam.” It seemed a doubtful combination to intrust to the mail service. Then her face lighted with a sudden resolution.

“Show me just where you live, Philip.”

The boy turned and pointed up the mountain.

“That big spruce grows by the house. It’s on the rocks behind it.”

“I see, Philip. I can find it easily. I must be going now, for the stage is waiting, but I shall stop a day or two at the mines below here. I will come to-morrow and learn just how to send the picture. Good-by till then, Philip.”

She took his thin brown hand in her own soft palm. The mother instinct welled up strong. She hungered to gather him to her breast, but he was already drawing back rather fearfully. A step away she turned to wave another good-by.

Peanut had disappeared among the bushes.

III

THE Rose of Texas sat in the open door of her cabin. The Rose might have been beautiful once—it is proper to give any woman past middle age the benefit of this possibility—and there may have been a time when the Rose had deserved her name and been fully equal in value to the Colt .44, three ponies, and five hundred dollars in gold which Sam had stacked up against her, and so, with the aid of three other knaves, attached her to his household. On a stone a few feet distant sat Peanut, in deep reverie. The Rose was first to break the silence.

“I reckon it’s the best thing for you, Peanut,” she said, and there was a sort of resolute hopelessness in her voice. “It’ll be mighty lonesome, of course, without you, but when you get so you can write you can send me a letter now and then. I guess I can read ’em. I ain’t tried any for a good while, but if you make ’em plain, mebbe I can spell ’em out. It’s a good chance, Peanut, an’ I don’t s’pose you’d ever get another. Then you’ll learn figgerin’, too.”

“What’s that, Rose? What’s figgerin’?”

“Why, it’s like writin’, only it’s countin’, on paper. It’s to keep folks from cheatin’ you, in a trade.”

Peanut recalled his experience with the boy at the mines. The boy probably knew about figgerin’.

“How long does it take to learn figgerin’, Rose?”

“Oh, I dun’no’. Mebbe a year.”

“Then can I come back to you—an’ the bears, an’ Sam’s grave?”

“You won’t want to. You’ll be learnin’ other things an’ seein’ new places an’ fine folks. You won’t want to come back to the hills, even if you could. But you can write, an’ you’ll have a picter of Sam’s grave, like the kind she showed us to-day. She seems like she’d be mighty good to you, an’ I reckon you’ll have to go, Peanut.”

“But I’m comin’ back, Rose, when I’ve learnt figgerin’ an’ seen all the places. I’m comin’ back to locate a mine an’ make money for us. You can’t stay here always alone. An’ our bears would forgit me if I was gone too long. You’ll feed ’em jest the same, won’t you, Rose, when I ain’t here?”

The woman’s voice broke a little as she assured him that the big brown bears that lumbered down the mountain every day for refuse should still be cared for in his absence.

“She’s comin’ in the mornin’,” the Rose continued, “an’ if yer goin’, you want to be ready. Put on yer winter shoes an’ yer hat an’ yer other shirt. ’Tain’t much of a outfit, but it’s more’n you come with, an’ she’s goin’ to pervide fur you. I’ve got a little scrap o’ money, though, Peanut, an’ I want you to take it along. You ain’t to spend it unless somethin’ happens an’ she ain’t there. She’ll pervide when she is. Jest keep it so you know where it is. If you ever get lost, er need anything when she ain’t at home, then use it, but keep it as long as you can.”

The woman’s hand had gone down to the hem of her skirt and under her knee. It came up holding a small roll of currency.

“There’s ten dollars here, Peanut; it won’t buy much, but it would go a long ways if you was lost and hungry. Keep it in the little sack, with Sam’s ambertype an’ the last whistle he made you, an’ don’t let the sack out o’ yer hands.”

The boy took the money curiously. He had never possessed any before. He opened the bills and looked first at one, then at the other. He went into the cabin presently and deposited them in a small buckskin bag which Sam had given him for his treasures. When Miss Schofield appeared next morning he was sitting stiffly in his winter shoes and hat, his wet, faded hair plastered close, the little bag concealed about his neck. He was quite ready.

The Rose was wiping her eyes as she saw them pass down the mountain in the direction of Sam’s grave. She was wondering what she was going to do without Peanut. She did not realize that perhaps Cynthia Schofield was wondering equally what she was going to do with him—what was to be the outcome of the philanthropic impulse and heart hunger that had led her into taking the pathetic little creature by her side, away from his beloved hills, to begin a new development in a strange atmosphere and amid alien surroundings.

But if Miss Schofield had any misgivings as to the wisdom of her undertaking, she was upheld by the thought that her purpose was altogether righteous, and would be justified by results. The fact that as they passed Sam’s grave Peanut flung himself upon it and wept, and refused to be comforted, only strengthened her belief that he would one day glorify her for having removed him from the influence of former companionships.

IV

IT having developed that at some former period Blazer Sam had been known by the surname Hopkins, Miss Schofield had agreed with the Rose that the latter should receive her mail under the very respectable superscription of Mrs. Rose Hopkins, and at the camp post-office arrangements had been made to this end. Miss Schofield had further agreed to write. Also that Peanut should write as soon as he was able to do so.

If the Rose went oftener to the camp now, and, bringing home heavier bundles, filled longer days with harder work, it may have been only that she was providing for an old age that could not be far distant, or very luxurious at best.

If the mail service possessed a new attraction for her, she did not show it. Her years of lonely secretive life had been not without their effect. She made no inquiries for letters, and seemed rather surprised when one day in September the storekeeper, who was also postmaster, laid a sealed envelope with her package of coffee on the counter.

Both the address and the letter were printed—type-written. The Rose did not understand this process, and was deeply grateful to Miss Schofield for taking extra pains to make the reading easy. It was not a long letter, telling only of her safe arrival in Chicago with Philip, and the fact that he was already at school, where he would learn very fast. Her friends thought a great deal of her “little mountain boy,” but she was trying not to let them spoil him. She wished to keep his nature as fresh and beautiful as the mountains themselves, adding only such education as would make him understand the higher life, and such knowledge of the world as would fit him to take his part in it by and by. Philip had sent greetings to “Rose and the bears.” He would write before long, himself. He could already shape the letters, and was at his work constantly. If the Rose needed anything, she was of course to let Miss Schofield know. Meantime, she remained, etc., etc.

On the whole it was a satisfactory missive. Peanut was safe and remembered her. He was learning to write, and would send, by and by, letters of his own. To the Rose of Texas the type-written sheet containing these assurances became of more value than all her former possessions. She pinned it against the cabin wall where she could see it and pause before it as she passed in her work.

Only, in one sentence of the letter there was a pang. She had called him her “little mountain boy.” The Rose wondered vaguely if this meant that she herself had surrendered all claim. The sentence about the “higher life” rather pleased her. She took it to mean a more pretentious mode of living. If Peanut should visit her by and by he would probably come in a buggy, wearing a high hat such as she had seen on rich mine speculators. She resolved to make an effort herself to live up to this higher life and so preserve something of her claim on Peanut.

She recalled a tradition that women of the higher life did not drink whisky—at least not regularly. She would give up her toddies—by degrees, of course—but in time enough to do without them almost altogether when Peanut arrived. In the matter of clothes, she had noticed that those worn by Miss Schofield had been quite plain, not at all like her own gaudy finery of former years. She would get some very plain clothes, gradually, as she could earn the money, and have them ready for Peanut’s return. She would also piece together the remnants of her meager education.

She obtained at once such literature as could be had at the camp, and patiently pored over a government survey, and a mutilated primary arithmetic contributed by one of her patrons. A line to Miss Schofield would have brought her quantities of educational matter, but this fact did not occur to her. Indeed, the possibility of ever writing at all did not enter into her dreams.

In October came the first letter from Peanut:

The writing was very round and plain. It seemed marvelous to the Rose that he could do it already. He would reach the higher life sooner than she had thought. She would leave out her “between” toddies to-morrow.

A week later brought still another letter. Already there was improvement.

After that, letters came almost every week, and became the chief life interest of the lonely woman above the clearing. She pinned them side by side to the wall of her cabin, that she might read them without the wear of handling. She learned each by heart as it came, but this in no way destroyed the joy of after-perusal. She compared the writing, too, and his rapid improvement gratified her and spurred her to vigorous new efforts of her own.

I may say here that the boy’s progress gratified Miss Schofield as well. Alert, eager, sensitive to new impressions, Peanut in two months had overtaken many of his own age. Some he had passed altogether. In a November letter, he wrote:

“There is a rale-road here that runs up in the air, and rale-roads on the groun that go all the time, day an nite. I want to see you and the bears and Sams grave. And I want to be in the woods where there are no rale-roads.”

The evident homesickness of this letter touched the Rose deeply. The “rale-road in the air” made her marvel.

The next letter contained further information.

“Wim-men here do not smoak. And they do not say dam. I mean wim-men like Miss Schofield.”

The Rose had never been given to profanity. It had been a luxury, to be indulged in on rare occasions. She could forego it easily. Her pipe would be a harder matter. Harder even than her toddy—yet, she must do it—she would begin at once. She resolved that nothing should stand between her and a share in that higher life for which Peanut was destined.

Later in November there came a letter in which he said:

“The people here have white stones at their graves in-sted of boards. They call them marble. They put their names on them, and when they was born and was kild, or died. They are not alwis kild here. I wish Sam had a white mar-ble stone with his true name on it. We could keep the other too. They have one at each end. When I come back I will by one.”

The Rose toiled earlier and later than before. She no longer had time for solitaire. She also grew thinner, and a new look had come into her face. The possibility of former beauty could be more easily accorded. A miner from the camp came one day and wanted to marry her. Some trace of a far-off former life of coquetry made her laugh and say to him:

“You’re too late. I’ve a sweetheart already. He’s coming in a buggy, with fine clothes on, and a high hat.”

The miner went back to camp and reported that the Rose had caught a speculator, who would take her to Ogden in the spring.

Autumn became winter. The bears went to sleep in their cave, and came no more to the cabin. Blazer Sam’s grave was lost in folds of white, and at times the lone woman above the clearing was shut in for days. But though alone, she was no longer lonely. With work and the letters upon the wall her days had become as dream-days, her nights brief periods of untroubled sleep. It was only when the passes were blocked and detained the stage with Peanut’s letter that she minded the storm. At one time the delay was long. Then she received two, and was proportionately gratified. In the longer of these he wrote:

“Miss Schofield gives shose. She has a lant-ern that makes pic-tures on a big sheet. They are seens of where she goes. Last night she shode the mines and told about them. Then she shode Sams grave with me a-sleep on it, and it was as big as it is there. She came and took my hand and led me up in front of the peo-ple and told them it was the grave of the cel-ib-ra-ted Sam Hopkins, and that he had been called Blazer Sam, and how she found me asleep on his grave, and how he used to make me whissels and go with me over the mount-ins. And how he must have had a good hart to care so much for a lit-tle boy. And when I saw the picture so big and plain and heard how much she liked Sam too, I had to cry, and Miss Schofield says that then all the peo-ple cried, and that she must not do it again. If Miss Schofield was not so good I would come back. I think about the bears up in their cave a-sleep, and how the snow is on Sams grave, and how lonesome you must be there alone. She is almost as good as Sam, and I know now that Sam belonged to the hire life. I guess he lerned it when he was away so much.”

It is doubtful if Miss Schofield saw all the letters which Peanut wrote to the Rose. I have reason to believe that she saw none of them after the first, and that one only to be sure that it was legible and properly addressed. She meant to be liberal, and was so, according to her lights. Her favorite word was “spontaneity” and she was eager to allow the boy his own privacy and expression—any form of freedom, indeed, that did not conflict with the lives of others or with his spiritual development.

Concerning his former guardian and beloved hero, she carefully avoided any suggestion that would tend to destroy a beautiful illusion of childhood. In the boy’s dream-life Sam had been all that he appeared, and there must be no rude awakening. Little by little, as we learn the truth about Santa Claus and fairies, and never wholly lose faith in them, so in due course and almost imperceptibly would come enlightenment and a truer understanding.

But this attitude did not prevent Miss Schofield from dilating upon the lurid history of Blazer Sam in her entertainment, as usually given. Peanut was absent at such times, and the audience unknown to him. It was one of her choicest bits, and the grim humor of it was only heightened by the touch of pathos supplied by the picture of the grave with the sleeping figure of Peanut, the story of his devotion to the outlaw, and his present relation to herself. As I have said, Miss Schofield was, before all, the artist.

Nor would it be fair, I think, to attach blame to Miss Schofield for what the super-sensitive reader might regard as a certain disloyalty to Peanut. Certainly it was proper to leave his faith in Sam’s goodness undisturbed, at least through the boy’s trusting childhood; while it was no less justifiable to make such use of the facts as would best serve their artistic presentation. The ends of art have justified conditions far more questionable than these, and her error, if there was an error, would seem to have been an earlier matter—committed on that August day when, following a sudden half-romantic, half-philanthropic impulse, she was prompted to transplant, to a crowded and noisy environment, a life so essentially a thing of the open sky and the wide freedom of the hills. But perhaps there are no mistakes in this world. A good many otherwise reasonable persons hold by this doctrine.

V

MISS Schofield had been careful to see that Peanut was in bed and asleep on that night in June when the schools closed and she was giving a cozy supper to her fellow-teachers. Ever since the breaking of the buds in the park the boy had been restless, and she did not wish him to be disturbed by the voices and merriment of her company. Then, too, a little private exhibition of some of her choicest “in-gatherings” would follow, and it would not do for her group of special friends to be deprived of any feature of her collection. They would be quite sure to want the outlaw’s grave and her picturesque narrative accompaniment.

She bent over the sleeping boy and listened to his heavy breathing. What a joy and comfort he was to her! She had felt his hunger for the open air and the breath of the mountains. Yet how faithful he had been to his books—how little he had mingled with the sports of other children! He was of different fiber. And what progress he had made! Some day the world would honor and claim him. Now he was all hers—her captive wood-creature—her dreamer, her poet! She bent over and lightly kissed his hair. Sometimes she had strained him to her bosom. She longed to do so now, but a moment later was stepping silently to the door, then as silently she closed it and drew the heavy curtain without.

Miss Schofield was not mistaken in the expectations of her guests. Like their pupils, the merry teachers rejoiced in a newly acquired freedom and wished to be amused. In the darkened parlor they forgot the year’s restraints and labors and gave themselves up to luxury of enjoyment.

As the gem of the programme, the Blazer’s grave was held for the last. When at length it was thrown upon the sheet there was a chorus of approval and a round of applause. And Cynthia Schofield rose to the occasion. She had never been so full of joy in the present, so satisfied with what life had brought to her in the past, so pleased with the outlook ahead. The picture on the screen was a part of these happy conditions, her audience inspiring. Her friends expected the best, and they should have it. With what subtle art she led up to the incident: The stopping of the stage, the driver pointing up the hillside with his whip. Then the scaling of the steep ascent, the pausing here and there to look down upon the scene of the outlaw’s former crimes, which she recalled, as she had heard them, in the vernacular of the hills. Next, her entrance to the little clearing about the grave—the black stumps, the flowers—and Peanut on the grave, asleep. And her interview with Peanut! She made it a masterpiece! She even may have colored it a little—the ends of art would justify that, too. The imitation of Peanut’s voice, and his monotonous reading of the profane and half-comprehended epitaph—she gave them with a fidelity that startled even herself. Her friends became hysterical. At one moment sobbing and wiping their eyes, at the next laughing, the tears still running down their cheeks. And then the picture she drew of the Rose of Texas, and of Peanut when he sat waiting for her to take him away. “Worthy of Dickens!” they cried out to her. “You must write it, Miss Schofield! You must certainly write it!”

But Miss Schofield will never write that scene, and those of us who listened that night in June heard not only its greatest presentation, but its last. A moment later the lights went up, and she turned for congratulations. Then she saw him. He stood just inside the door, and his face was like death.

The prolonged merriment had found its way through the heavy curtain and closed door. Unable to sleep, he had dressed and come out to find the cause. He had never been forbidden any part of the house, and at the entrance of the darkened parlor had listened in silence to the entertainment that ended with ridicule and defamation of his hero, with jeers of laughter for himself and Rose. Once more he had met with deception—this time in one whom he had trusted and loved, even as he had loved and trusted Sam—in her, of all others, who had promised to lead him to the higher and better life.

As white and death-like as himself, Cynthia Schofield led him back to his bed. There she tried to speak to him.

Peanut turned his face to the wall.

VI

THE letter which the postmaster handed to the Rose of Texas seemed heavier than usual. The Rose hugged it all the way up the mountain. Then out on the doorstep, where he had said good-by, she opened and read it. The first sentence made her heart leap:

Dear Rose,—I am coming back. I will start before morning. If I go west and keep on every day, some day I will get there. Miss Schofield told me once that it was fifteen hundred miles, so if I can walk fifteen miles a day it will take me a hundred days to get to the cabin and Sam’s grave. The money you gave me is not enough to come on the cars. I will spend it for things to eat. At ten cents a day it will last till I get home. Perhaps some days I won’t need to spend so much. I will wear the clothes you made me and my own hat and shoes. I have them all on now, and the lether sack with Sam’s ambertipe and the whissel, and the money. I would like to take the picture of the grave, but I shall leave it on the wall.

I wrote you how Miss Schofield showed the picture of the grave and told about Sam’s good heart. When I am not there she tells how he had a cruel heart and was only good to me. And it is not true, and when she told how she met me at Sam’s grave she told other things that were not true, and that did not happen at all. She laughs at Sam and the grave and at you and me. And she makes other people laugh. That is all she cares for. I thaut she was like Sam, but she is not and I could not be good here either, where there are so many bad people and nothing is clean. The snow is so dirty here they take it right away and you can never hear the wind and rain. They have trees in the park and animals and birds in cages, but they make me cry because they are so homesick, like me. I want to come back to the hills where there is just you and the bears and Sam’s grave. If I start to-night and it takes a hundred days it will be more than a year since I went away. I will never leave you any more. I am obliged to Miss Schofield for sending me to school, but I cannot stay here now. I was yours before I was hers, and I will be yours again. Perhaps I can get some books and study lessons there with you and learn to be a naturallist, when I grow up, which means to live in the woods and know about the birds and animals, and I will dig gold out of the mines for us and I will put a white stone at Sam’s grave so we can see it from every-where.

Now I am going to start. I am going to slip down-stairs and I will be out in the country before morning. Sam taut me how to hide, and how to keep in one direction. Perhaps I will write to you on the way, but I must not buy many stamps or paper. Anyway I will be coming all the time, and some day I will be there the same as ever.

Yours,

Peanut.

The Rose of Texas was a bundle of conflicting emotions by the time she reached the end of this letter. But out of it all came one dominant joy. Peanut was coming back to her—he was already on the way. Whatever resentment she may have felt toward Miss Schofield was swallowed up in this great fact.

As to Peanut’s ability to make the long journey, she did not question it—not yet. She knew, of course, that the way was long, and would be hard in places. How long or how hard, neither she nor any one could know. She realized much more fully Peanut’s subtle knowledge of outdoor life, his persistence, and the endurance of his wiry little frame. She forgot that a winter of comparative inaction and close mental application might have told on his physical powers. It would be a weary journey, but with the long days of summer-time at hand he would not fail, and September would bring him back to her.

She would begin preparing for him at once. She would make up one of the new dresses, and leave off her second toddy to-morrow. Then there was another purpose, which must be accomplished now, sooner than she had expected. Her boy was coming back to her—not as she had once dreamed, in a buggy, and wearing a tall silk hat—but, better still, the boy who had gone away. He would find her ready to receive him.

But one thing troubled the Rose—the amount of Peanut’s resources. With the aid of her fragmentary arithmetic she verified his calculation that if a little boy traveled fifteen miles a day, and traveled a hundred days, he would travel fifteen hundred miles; also, if the same little boy had ten dollars, and spent ten cents of it every day, he would have enough to last him through the journey. Only, she wished that he might have more than ten cents a day. It seemed to her so little—she wondered what he would buy with it. Crackers, mostly, she thought, and cheese. The Rose thought of the eatables kept at the camp store, and sighed as she remembered how little of them could be had for ten cents. If she only knew where to send him more money. But she remembered hearing that things were cheaper beyond the mountains, and this thought consoled her.

As the days passed, her confidence in Peanut’s ability to make the long trip began to wane. Chicago lay far to the eastward, across rivers and beyond mountains. She reasoned that there must be a road and bridges between, but in her imagination she began to see the dusty little figure toiling along in the sun, overcome by thirst and heat, where the prairies were wide, and the houses far apart. At times she pictured him as being run down by those terrible railroad trains, as waylaid and robbed of his little store of money and left by the roadside to die. Almost clairvoyantly, at night, she saw him asleep in fence-corners, in haystacks, under bushes and ledges of rock—anywhere that afforded shelter to the friendless little wayfarer toiling back to his beloved hills. When the storm raged down the mountains she would open the door and, looking out into the mystery of blackness, fancy she heard his thin voice calling to her above the roar of the torrent and the wail of the tree-tops. However busy her days, they no longer seemed brief, her nights were no longer untroubled. She knew that he was still far away beyond the mountains, yet twenty times a day she hastened to the door to look and listen, while at night wild dreams brought her bolt upright to answer to his call.

When two weeks had passed the stage one day brought her two letters. One of them from Miss Schofield—written from a sense of duty, we may believe—told, briefly and guardedly, of the strange disappearance of Peanut. The writer assured the Rose that there was no cause for uneasiness, that every effort was being made to find the missing boy and that he was certain to be discovered in a brief time. The Rose smiled grimly as she read this epistle, for the other one had been from Peanut—just a line on a bit of wrapping-paper, to tell her that in seven days he had reached Iowa, which was farther than he had expected to be at that time. People had asked him to ride, sometimes, on their wagons. There were nearly always good places to sleep—mostly in the woods, where he had the birds and squirrels for company. He was well, and happier than he had been for a year.

The Rose did not know where Iowa was. When she asked the postmaster he showed it to her on the map. Then she did not know any better, but she was comforted. Peanut wrote again when he reached Nebraska, but that was nearly three weeks later, and the Rose had become almost desperate. Now she was made briefly happy by the statement that he was still well, and had money, and that he had found there were only two more states to cross, Nebraska and Wyoming, and then a little more and he would be home.

To the Rose a state was a state. That the distance yet to be traveled was double that already covered, and many times more difficult, did not occur to her. But when two weeks more had passed, and yet two more, and brought no further word from the little wayfarer, her heart grew very heavy again, and she haunted the camp post-office with each arrival of the stage.

And still another two weeks went by, and yet he did not come, and the days brought her no word. She did not know that the number of crackers obtained by Peanut for five cents had been reduced in his westward march from ten to eight, from eight to six, and that the bit of cheese received in exchange for the other five cents had grown so small that the little boy, alarmed, had feared to spend even the money necessary for another letter. The Rose did not know these things, and even had she known, it would hardly have lessened her anxiety.

She spent most of her time now in watching for him. The hundred days had by no means expired, but his letters had led her to hope that he had gained time and would be there sooner than he had calculated. According to her count, if a little boy could cross two states in four weeks, he could cross four states and something over in about nine weeks, and now twelve weeks had gone by and he had not come. The fact that he no longer wrote encouraged her to believe that at any moment he might walk in upon her.

But now came an added anxiety. A letter, indeed, not from Peanut, but a broken-hearted confession from Cynthia Schofield, who, good woman that she was, acknowledged everything, begging the Rose to forgive her, and to write if she knew aught of their little lad.

“It was all so strange and unsuited to him here,” she wrote. “I can see, now, how he belonged only there in those beautiful hills and how his life there would mean more to him, and to others, too, I believe, than here in the sordid clatter and struggle and deception that he could not endure—” Then, in closing, she added: “Sometimes I think he must have started home, and I am having notices posted and published all along the way, so that somebody may find him and keep him safely until I come. Poor little fellow! Where is he, and what is he doing to-night, out all alone in this great wicked waste of a world?”

The Rose comprehended little more than the grief of this letter, and she pitied Miss Schofield, as one woman may pity another when there is but one heart’s desire for both; but her sympathy vanished in the fear that Miss Schofield’s agents with their wide knowledge and ample resources would find the boy after all and that to her, the Rose, he would now be lost forever.

She was in a frenzy of suspense. A hundred times she would have closed the cabin and gone to meet him, but feared she might pass him by a different way, and so wander on and on helplessly. Her anxiety at last overcame her secretiveness, and she one day partially unburdened herself to the postmaster, who informed her that for at least fifty miles to the eastward there was but one road. This was in September, more than three months from the night that Peanut had left Miss Schofield’s apartment in Chicago. The Rose could wait no longer. She set out to meet him the same afternoon.

She put on one of her new plain gowns, and a new, though not altogether plain bonnet which the storekeeper had ordered for her from Ogden. She started to put on her new shoes, too, but, remembering that she might have far to walk, held to the old ones. Then she packed a basket with eatables—good things such as Peanut had always liked. He would be tired of the things he could buy with his ten cents a day along the road. Tired? dear heart! As if a little boy trudging over range after range of lofty mountains, only to find range after range of still loftier ones beyond, could be tired of any kind of food! The Rose imagined how he would welcome the freshly cooked bread, and the coffee which she would make in the little pail. She felt much less unstrung now that she was really going to meet him, and more nearly happy than she had been for weeks. Only, she must hurry, and get as far as possible before nightfall. Over her arm she threw a thick army blanket, for sleeping on the ground.

It was well on toward two o’clock when she started. The path led by Sam’s grave, and she paused an instant to regard the place with a new pride. Then she pressed on—there would be time enough for this afterward.

The Rose of Texas found it hard climbing the mountain road. She began to realize now why it was that Peanut might be longer than he had counted on, and her heart ached for him more, and her arms ached, too, under the heavy load of blanket and basket. When she had been toiling up the hill for perhaps three hours she wondered how many miles she had come. But at a high turn of the road she paused to look back, and was surprised to see—almost behind her, it seemed—her own steep hillside, with the little clearing about Sam’s grave. It was fully six or seven miles away, but in that clear air it seemed almost as if she might reach out and touch it. Wearily she pushed on. Dark fell, and she halted for the night.

It grew very cold. The Rose attempted to kindle a fire, but she could not find dry pieces, and the matches flickered and smoldered to blackness. She huddled down in her blanket at last, realizing what this night must mean to a hungry little boy with nothing but the sky to cover him. Perhaps experience had taught Peanut a better means of providing, but the Rose did not consider this, and through the bitter night saw him crouching in the dark, shivering with cold and exposure. She did not sleep, and before daybreak was toiling up the long incline.

The way grew ever steeper: she was nearing the mountain-top. It grew lighter, too, and presently she noticed that the trees ahead were fringed with morning. The sun was coming.

The fringe crept lower, the woods on either side turned to amethyst, a spot of radiance lay on the high trail between. The Rose paused and, looking up, gave welcome to the new day.

Then, all at once, in the patch of sunrise ahead, something dark appeared; something that moved, hesitated, moved again, stopped. The woman’s knees began to tremble exceedingly. Hastily shifting her burdens, she shaded her eyes and looked steadily into the brightness. Then she was sure. It was Peanut, and the glory behind him set a halo upon his faded hair.

The wayfarer had returned. Who shall say across what desert wastes, through what dark gorges, and by what dizzy heights the long path had led him home—had brought him nearer to the abiding comfort of Sam’s quiet grave and the rest of the enduring mountains? Who shall determine what unseen power had sustained that frail body and guided those wandering feet?

He had not seen her. She was in the shadow beneath, and he seemed looking over her head to some faraway point beyond. For one supreme instant the woman lingered to drink in the vision. Then basket, blanket, and old restraints fell away as she pressed up the slope, the new dawn shining in her face. He looked down then and saw her. These two had never embraced, but a moment later he was in her arms and their tears mingled.

“Peanut, oh, my poor little boy, how thin you are!”

“Oh, Rose, Rose! You bought it for him, didn’t you?”

For behold, from that high point the steep clearing on the far-off hillside was once more visible. But the black stumps were no longer to be seen, and in their place a white stone gleamed with the radiance of morning.

- Transcriber’s Notes:

- Missing or obscured punctuation was corrected.

- Unbalanced quotation marks were left as the author intended.

- Typographical errors were silently corrected.

- Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation were made consistent only when a predominant form was found in this book.