IN INDIAN TENTS

IN INDIAN TENTS

Stories

TOLD BY PENOBSCOT, PASSAMAQUODDY

AND MICMAC INDIANS

TO

ABBY L. ALGER

![]()

BOSTON

ROBERTS BROTHERS

1897{4}

Copyright, 1897,

By Roberts Brothers.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, U.S.A.

This Book

IS

AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED

TO

CHARLES GODFREY LELAND,

TO WHOSE INSPIRATION IT OWES

ITS ORIGIN.

PREFACE

In the summer of 1882 and 1883, I was associated with Charles G. Leland in the collection of the material for his book “The Algonquin Legends of New England,” published by Houghton and Mifflin in 1884.

I found the work so delightful, that I have gone on with it since, whenever I found myself in the neighborhood of Indians. The supply of legends and tales seems to be endless, one supplementing and completing another, so that there may be a dozen versions of one tale, each containing something new. I have tried, in this little book, in every case, to bring these various versions into a single whole; though I scarcely hope to give my readers the pleasure which I found in hearing them from the Indian story-tellers. Only the very old men and women remember these stories now; and though{8} they know that their legends will soon be buried with them, and forgotten, it is no easy task to induce them to repeat them. One may make half-a-dozen visits, tell his own best stories, and exert all his arts of persuasion in vain, then stroll hopelessly by some day, to be called in to hear some marvellous bit of folk-lore. These old people have firm faith in the witches, fairies, and giants of whom they tell; and any trace of amusement or incredulity would meet with quick indignation and reserve.

Two of these stories have been printed in Appleton’s “Popular Science Monthly,” and are in the English Magazine “Folk-Lore.”

I am under the deepest obligation to my friend, Mrs. Wallace Brown, of Calais, Maine, who has generously contributed a number of stories from her own collection.

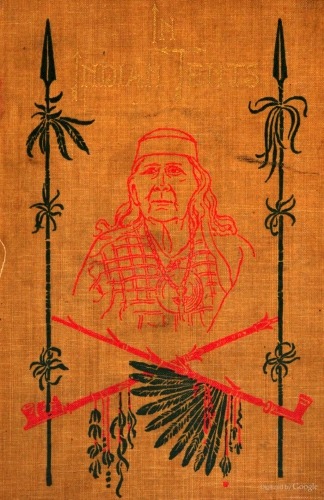

The woman whose likeness appears on the cover of this book was a famous story-teller, one of the few nearly pure-blooded Indians in the Passamaquoddy tribe. She was over eighty-seven when this picture was taken.{9}

CONTENTS

IN INDIAN TENTS

THE CREATION

In the beginning God made Adam out of the earth, but he did not make Glūs-kābé (the Indian God). Glūs-kābé made himself out of the dirt that was kicked up in the creation of Adam. He rose and walked about, but he could not speak until the Lord opened his lips.

God made the earth and the sea, and then he took counsel with Glūs-kābé concerning them. He asked him if it would be better to have the rivers run up on one side of the earth and down on the other, but Glūs-kābé said, “No, they must all run down one way.”

Then the Lord asked him about the ocean, whether it would do to have it always lie still. Glūs-kābé told him, “No!” It must rise and fall, or else it would grow thick and stagnant.{12}

“How about fire?” asked the Lord; “can it burn all the time and nobody put it out?”

Glūs-kābé said: “That would not do, for if anybody got burned and fire could not be put out, they would die; but if it could be put out, then the burn would get well.”

So he answered all the Lord’s questions.

After this, Glūs-kābé was out on the ocean one day, and the wind blew so hard he could not manage his canoe. He had to go back to land, and he asked his old grandmother (among Indians this title is often only a mark of respect, and does not always indicate any blood relationship), “Māli Moninkwess” (the Woodchuck), what he could do. She told him to follow a certain road up a mountain. There he found an old man sitting on a rock flapping his wings (arms) violently. This was “Wūchowsen,” the great Wind-blower. He begged Glūs-kābé to take him up higher, where he would have space to flap his wings still harder. So Glūs-kābé lifted him up and carried him a long way. When they were over a great lake, he let Wūchowsen drop into the water. In falling he broke his wings, and lay there helpless.{13}

Glūs-kābé went back to sea and found the ocean as smooth as glass. He enjoyed himself greatly for many days, paddling about; but finally the water grew stagnant and thick, and a great smell arose. The fish died, and Glūs-kābé could bear it no longer.

Again he consulted his grandmother, and she told him that he must set Wūchowsen free. So he once more bore Wūchowsen back to his mountain, first making him promise not to flap his wings so constantly, but only now and then, so that the Indians might go out in their canoes. Upon his consent to do this, Glūs-kābé mended his broken wings; but they were never quite so strong as at first, and thus we do not now have such terrible winds as in the olden days.

This story was told to me by an old man whom I had always thought dull and almost in his dotage; but one day, after I had told him some Indian legends, his whole face changed, he threw back his head, closed his eyes, and without the slightest warning or preliminary began to relate, almost to chant, this myth in a most extraordinary way, which so startled me that I could not at the time take any notes of{14} it, and was obliged to have it repeated later. The account of Wūchowsen was added to show the wisdom of Glūs-kābé’s advice in the earlier part of the tale, and is found among many tribes.{15}

GRANDFATHER THUNDER

During the summer of 1892, at York Harbor, Maine, I was in daily communication with a party of Penobscot Indians from Oldtown, among whom were an old man and woman, from whom I got many curious legends. The day after a terrible thunderstorm I asked the old woman how they had weathered it in their tents. She looked searchingly at me and said, “It was good.” After a moment she added, “You know the thunder is our grandfather?” I answered that I did not know it, and was startled when she continued: “Yes, when we hear the first roll of the thunder, especially the first thunder in the spring, we always go out into the open air, build a fire, put a little tobacco on it, and give grandfather a smoke. Ever since I can remember, my father and my grandfather did this, and I shall always do it as long as I live. I’ll tell you the story of it and why we do so.{16}

“Long time ago there were two Indian families living in a very lonely place. This was before there were any white people in the land. They lived far apart. Each family had a daughter, and these girls were great friends. One sultry afternoon in the late spring, one of them told her mother she wanted to go to see her friend. The mother said: ‘No, it is not right for you to go alone, such a handsome girl as you; you must wait till your father or your brother are here to go with you.’ But the girl insisted, and at last her mother yielded and let her go. She had not gone far when she met a tall, handsome young man, who spoke to her. He joined her, and his words were so sweet that she noticed nothing and knew not which way she went until at last she looked up and found herself in a strange place where she had never been before. In front of her was a great hole in the face of a rock. The young man told her that this was his home, and invited her to enter. She refused, but he urged until she said that if he would go first, she would follow after. He entered, but when she looked after him she saw that he was changed to a fearful, ‘Wī-will-mecq’—a loathly worm. She shrieked, and turned to{17} run away; but at that instant a loud clap of thunder was heard, and she knew no more until she opened her eyes in a vast room, where sat an old man watching her. When he saw that she had awaked, he said, ‘I am your grandfather Thunder, and I have saved you.’ Leading her to the door, he showed her the Wī-will-mecq, dead as a log, and chopped into small bits like kindling wood. The old man had three sons, one named ‘M’dessun.’ He is the baby, and is very fierce and cruel. It is he who slays men and beasts and destroys property. The other two are kind and gentle; they cool the hot air, revive the parched fields and the crops, and destroy only that which is harmful to the earth. When you hear low, distant mutterings, that is the old man. He told the girl that as often as spring returned she must think of him, and show that she was grateful by giving him a little smoke. He then took leave of her and sent her home, where her family had mourned her as one dead. Since then no Indian has ever feared thunder.” I said, “But how about the lightning?” “Oh,” said the old woman, “lightning is grandfather’s wife.”

Later in the summer, at Jackson, in the White{18} Mountains, I met Louis Mitchell, for many years the Indian member of the Maine Legislature, a Passamaquoddy, and asked him about this story. He said it was perfectly true, although the custom was now falling into disuse; only the old people kept it up. The tobacco is cast upon the fire in a ring, and draws the electricity, which plays above it in a beautiful blue circle of flickering flames. He added that it is a well-known fact that no Indian and no Indian property were ever injured by lightning.{19}

THE FIGHT OF THE WITCHES

Many, many long years ago, there lived in a vast cave in the interior of a great mountain, an old man who was a “Kiāwākq’ m’teoulin,” or Giant Witch.

Near the mountain was a big Indian village, whose chief was named “Hassagwākq’,” or the Striped Squirrel. Every few days some of his best warriors disappeared mysteriously from the tribe, until Hassagwākq at last became convinced that they were killed by the Giant Witch. He therefore called a council of all the most mighty magicians among his followers, who gathered together in a new strong wigwam made for the occasion. There were ten of them in all, and their names were as follows: “Quābīt,” the Beaver; “Moskwe,” the Wood Worm; “Quāgsis,” the Fox; “K’tchī Atōsis,” the Big Snake; “Āgwem,” the Loon; “Kosq,” the Heron; “Mūin,” the Bear; “Lox,” the{20} Indian Devil; “K’tchīplāgan,” the Eagle; and “Wābe-kèloch,” the Wild Goose.

The great chief Hassagwākq’ addressed the sorcerers, and told them that he hoped they might be able to conquer the Giant Witch, and that they must do so at once if possible, or else their tribe would be exterminated. The sorcerers resolved to begin the battle the very next night, and promised to put forth their utmost power to destroy the enemy.

But the Giant Witch could foretell all his troubles by his dreams, and that selfsame night he dreamed of all the plans which the followers of Striped Squirrel had formed for his ruin.

Now all Indian witches have one or more “poohegans,” or guardian spirits, and the Giant Witch at once despatched one of his poohegans, little “Alūmūset,” the Humming-bird, to the chief Hassagwākq’ to say that it was not fair to send ten men to fight one; but if he would send one magician at a time, he would be pleased to meet them.

The chief replied that the witches should meet him in battle one by one; and the next night they gathered together at an appointed{21} place as soon as the sun slept, and agreed that Beaver should be the first to fight.

The Beaver had “Sogalūn,” or Rain, for his guardian spirit, and he caused a great flood to fall and fill up the cave of the Giant Witch, hoping thus to drown him. But Giant Witch had the power to change himself into a “Seguap Squ Hm,” or Lamprey Eel, and in this shape he clung to the side of his cave and so escaped. Beaver, thinking that the foe was drowned, swam into the cave, and was caught in a “K’pagūtīhīgan,” or beaver trap, which Giant Witch had purposely set for him. Thus perished Beaver, the first magician.

Next to try his strength was Moskwe, the Wood Worm, whose poohegan is “Fire.” Wood Worm told Fire that he would bore a hole into the cave that night, and bade him enter next day and burn up the foe. He set to work, and with his sharp head, by wriggling and winding himself like a screw, he soon made a deep hole in the mountain side. But Giant Witch knew very well what was going on, and he sent Humming-bird with a piece of “chū-gāga-sīq’,” or punk, to plug up the hole, which he did so well that Wood Worm could not make{22} his way back to the open air, and when Fire came to execute his orders, the punk blazed up and destroyed Moskwe, the Wood Worm. Thus perished the second sorcerer.

Next to fight was K’tchi Atōsis, the Big Snake, who had “Amwess,” the Bee, for a protector. The Bee summoned all his winged followers, and they flew into the cave in a body, swarming all over Giant Witch and stinging him till he roared with pain; but he sent Humming-bird to gather a quantity of birch bark, which he set on fire, making a dense smoke which stifled all the bees.

After waiting some time, Big Snake entered the cave to see if the bees had slain the enemy; but he was speedily caught in a dead fall which the Witch had prepared for him, and thus perished the third warrior.

The great chief, Hassagwākq’, was sore distressed at losing three of his mightiest men without accomplishing anything, but still, seven yet remained.

Next came Quāgsis, the Fox, whose poohegan was “K’sī-nochka,” or “Disease,” and he commanded to afflict the foe with all manner of evils. The Witch was soon covered with boils{23} and sores, and every part of his body was filled with aches and pains. But he despatched his guardian spirit, the Humming-bird, to “Quiliphirt,” the God of medicine, who gave him the plant “Kī Kay īn-bīsun,”[1] and as soon as it was administered, every ill departed.

The next to enter the lists was Āgwem, the Loon, whose poohegan was “K’taiūk,” or Cold. Soon the mountain was covered with snow and ice, the cave was filled with cold blasts of wind, frosts split the trees and cracked asunder the huge rocks. The Giant Witch suffered horribly, but did not yield. He produced his magic stone and heated it red-hot, still, so intense was the cold that it had no power to help him.

Alŭmūset’s wings were frozen, and he could{24} not fly on any more errands; but another of the master’s attendant spirits, “Litŭswāgan,” or Thought, went like a flash to “Sūwessen,” the South Wind, and begged his aid.

The warm South Wind began to blow about the mountain, and Cold was driven from the scene.

Next to try his fate was Kosq, the Heron, whose guardian spirit was “Chenoo,” the giant with the heart of ice, who quickly went to work with his big stone hatchet, chopped down trees, tore up rocks, and began to hew a vast hole in the side of the mountain; but the Giant Witch now for the first time let loose his terrible dog “M’dāssmūss,” who barked so loudly and attacked Chenoo so savagely that he was driven thence in alarm.

The next warrior was Mūin, the Bear, whose poohegans were “Petāgŭn,” or Thunder, and “Pessāquessŭk,” or Lightning. Soon a tremendous thunderstorm arose which shook the whole mountain, and a thunder-bolt split the mouth of the cave in twain; the lightning flashed into the cavern and nearly blinded the Giant Witch, who now for the first time knew what it was to fear. He yelled aloud with pain,{25} for he was fearfully burned by the lightning. Thunder and Lightning redoubled their fury, and filled the place with fire, much alarming the foe, who hurriedly bade Humming-bird summon “Haplebembo,” the big bull-frog, to his aid. Bull-frog appeared, and spat out his huge mouth full of water, which nearly filled the cave, quenching the fire, and driving away Thunder and Lightning.

Next to fight was Lox, the Indian Devil. Now Lox was always a coward, and having heard of the misfortunes of his friends, he cut off one of his big toes, and when Striped Squirrel called him to begin the battle, he excused himself, saying that he was lame and could not move.

Next in order came K’tchīplāgan, the Eagle, whose poohegan was “Aplāsŭmbressit,” the Whirlwind. When he entered the enemy’s abode in all his fury and frenzy of noise, the Giant Witch awoke from sleep, and instantly “K’plāmūsūke” lost his breath and was unable to speak; he signed to Humming-bird to go for “Culloo,” the lord of all great birds; but the Whirlwind was so strong that the Humming-bird could not get out of the cave, being{26} beaten back again and again. Therefore the Giant Witch bade Thought summon Culloo. In an instant the great bird was at his side, and made such a strong wind with his wings at the mouth of the cave that the power of the Whirlwind was destroyed.

Hassagwākq’ now began to despair, for but one witch remained to him, and that was Wābe-kèloch, the Wild Goose, who was very quiet, though a clever fellow, never quarrelling with any one, and not regarded as a powerful warrior. But the great chief had a dream in which he saw a monstrous giant standing at the mouth of the enemy’s cave. He was so tall that he reached from the earth to the sky, and he said that all that was needful in order to destroy the foe was to let some young woman entice him out of his lair, when he would at once lose his magic power and might readily be slain.

The chief repeated this dream to Wābe-kèloch, ordering him to obey these wise words. Wild Goose’s poohegan was “Mikŭmwess,” the Indian Puck, a fairy elf, who speedily took the shape of a beautiful girl and went to the mouth of the cave, where he climbed into a tall hemlock-tree, singing this song as he mounted:{27}

Come list to my song,

Come forth this lovely night,

Come forth, for the moon shines bright,

Come, see the leaves so red,

Come, breathe the air so pure.”

Giant Witch heard the voice, and coming to the mouth of the cave, he was so charmed by the music that he stepped out and saw a most lovely girl sitting among the branches of a tree. She called to him: “W’litt hoddm’n, natchī pen eqūlin w’liketnqu’ hēmus,”—“Please, kind old man, help me down from this tree.” As soon as he approached her, Glūs-kābé, the great king of men, sprang from behind the tree, threw his “timhēgan,” his stone hatchet, at him and split his head open. Then addressing him, Glūs-kābé said: “You have been a wicked witch, and have destroyed many of Chief Hassagwākq’s best warriors. Now speak yet once again and tell where you have laid the bones of your victims.” Giant Witch replied that in the hollow of the mountain rested a vast heap of human bones, all that remained of what were once the mightiest men of Striped Squirrel’s tribe.

He then being dead, Glūs-kābé commanded all the birds of the air and the beasts of the{28} forest to assemble and devour the body of Giant Witch.

This being done, Glūs-kābé ordered the beasts to go into the cave and bring forth the bones of the dead warriors, which they did. He next bade the birds take each a bone in his beak and pile them together at the village of Hassagwākq’.

He then directed that chief to build a high wall of great stones around the heap of bones, to cover them with wood, and make ready “eqūnāk’n,” or a hot bath.

Then Glūs-kābé set the wood on fire and began to sing his magic song; soon he bade the people heap more wood upon the fire, and pour water on the steaming stones. He sang louder and louder, faster and faster, until his voice shook the whole village; and he ordered the people to stop their ears lest the strength of his voice should kill them. Then he redoubled his singing, and the bones began to move with the heat, and to sizzle and smoke and give forth a strange sound. Then Glūs-kābé sang his resurrection song in a low tone; at last the bones began to chant with him; he threw on more water, and the bones came together in their natural order and became living human beings once more.{29}

The people were amazed with astonishment at Glūs-kābé’s might; and the great Chief Hassagwākq’ gathered together all the neighboring tribes and celebrated the marvellous event with the resurrection feast, which lasted many days, and the tribe of Striped Squirrel was never troubled by evil witches forever afterward.{30}

ŪLISKE[2]

I was sitting on the beach one afternoon with old Louisa Flansouay (François) and the other Indians, when she suddenly rose with an air of great determination, saying to me, “Come into camp and I tell you a story!” (No story can ever be told in the open air; if the narrator be not under cover, evil spirits may easily take possession of her.)

I gladly followed old Louisa, who is a noted story-teller, and heard the following brief but thrilling tale.

Many, many years ago a great chief had an only daughter who was so handsome that she was always known by the name of “Ūliske,” which is to say “Beauty.” All the young men of the tribe sought her hand in marriage, but she would have nothing to say to them. Her father vainly implored her to make a choice;{31} but she only answered him, “No husband whom I could take, would ever be any good to me.”

Every year at a certain season, she wandered off by herself and was gone for many days; where she went no one could discover, nor could she be restrained when the appointed time came round.

At last, however, she yielded to persuasion and took a husband. For a time all went well. When the season for her absence was at hand, she told her husband that she must go. He said he would go with her, and as she made no objection, they set out on the following morning and travelled until they came to a lovely, lonely lake. A point of land ran out into the water, well wooded and provided with a pleasant wigwam. Here Ūliske beached the canoe; they went ashore and remained for two days and nights, when the husband disappeared. Ūliske in due time returned to her tribe and reported his loss. Her father and his followers sought long and anxiously, but no trace of him was ever found. Later on, Ūliske took a second husband, a third and a fourth, always quietly yielding to persuasion, and always saying as at first, that no husband whom she took could ever be{32} any good to her. One after the other visited with her the peninsula in the lake and disappeared in the same sudden and mysterious way.

The fifth husband was known as “Ū-el-ŭm-bek,” “the handsome, the brave,” and he made up his mind to solve the strange riddle of his predecessors. When he and Ūliske reached the peninsula, he said that, while she got supper, he would keep on in the canoe and see what fish or game he could find. He went but a little way, then drew the canoe up among the bushes and searched in every direction till he found a well beaten foot-path. “Now I shall know all,” he said, and hid himself behind a tree. Soon Ūliske came from the wigwam and went down to the water. Undressing herself, and letting down her long black hair, she began to beat upon the water with a stick and to sing an ancient Indian song. As she sang, the water began to heave and boil, and coil after coil slowly uprose above the surface a huge Wi-will-mekq’, a loathly worm, its great horns as red as fire. It swam ashore and clasped Ūliske in its scaly folds, wrapping her from head to foot, while she caressed it with a look of delight. Then Ū-el-ŭm-bek knew all. The Wi-willmekq’{33} had cast a spell upon Ūliske so that to her it appeared in the likeness of a beautiful young hero. The worm had destroyed her four husbands, and, had he not been prudent, would have drowned him as well. Waiting until Ūliske was alone, he returned to the wigwam before she had had time to wash off the slimy traces of Wi-will-mekq’s embraces, and charged her with her infatuation. Giving her no time to answer, he hurriedly chewed a magic root with which he had provided himself, flung it into the lake, thus preventing any attack as he crossed the water, got into the canoe and paddled away, leaving Ūliske to her fate, well knowing that as she had failed to supply her loathly lover with a fresh victim, she must herself become the prey of his keen appetite.

Rejoining his tribe, he frankly told his story. Even the chief declared that he had done well, and of Ūliske nothing more was ever heard.{34}

STORY OF WĀLŪT

In old times there were many witches among the Indians. Indeed, almost every one was more or less of a magician or sorcerer, and it was only a question as to whose power was the strongest.

In the days of which I speak, one family had been almost exterminated by the spells of a famous m’téūlin, and only one old woman named “M’déw’t’len,” the Loon, and her infant grandson were left alive; and she, fearing lest they should meet with the same fate, strapped the baby on her back upon a board bound to her forehead, as was the ancient way, and set forth into the wilderness. At night she halted, built a wigwam of boughs and bark, and lay down, lost in sad thoughts of the future; for there was no brave now to hunt and fish for her, and she must needs starve and the baby too. As she mourned her desolate state, a voice said in her ear: “You have a man, a brave man,{35} Wālūt,[3] the mighty warrior; and all shall be well if you will take the beaver skin from your old ’t’bān-kāgan,’[4] spread it on the floor, and place the baby on it.” This she did, and then fell peacefully asleep. When she waked, she saw, standing in the middle of the skin, a tall man. At first, she was terrified; but the stranger said, “Fear not, ‘Nochgemiss,’[5] it is only I!” and truly, as she gazed, she recognized the features of the baby whom she had laid upon the beaver fur, so few hours before. Even before day dawned, he had brought in a huge bear, skinned and dressed it. All day he came and went, bringing fish and game, great and small, and the old woman was glad.

Next morning, the skin which hung at the door of the wigwam was raised, and a girl looked in and smiled at Wālūt. His grandmother said, “Follow her not, for she is a witch, and would destroy you.” The next day and the next and so on, for five days, the same thing was repeated; but on the sixth day, the girl not{36} only lifted the curtain, but she entered in, went straight to Wālūt’s sleeping place and began to arrange his bed. This done, she drew from her bosom “nokoksis,” tiny brass kettles, and proceeded to cook a meal,—soup, corn and meat,—all in perfect silence. Grandmother watched her, but said nothing. When the meal was cooked, the girl set a birch-bark dish before grandmother and Wālūt, and began to ladle out the soup. Although the kettle was so small that it seemed no bigger than a child’s toy, both the dishes were filled and plenty then remained. No word was said; but when night came, the girl lay down beside Wālūt and thus, by ancient Indian law, became his wife. Their happy life, however, was of short duration, for the girl’s mother, “Tomāquè,” the Beaver, was a mighty magician, and was angry because her daughter had married without her consent. She therefore stole her away and deprived her of all memory of her husband and the past. Wālūt was determined to recover his bride, and his grandmother, wishing to help him, took from the old bark kettle a miniature bow and arrows. These she stretched and stretched until they became of heroic size. She strung the bow with a strand{37} of her own hair, and gave it to her grandson, telling him that no arrow shot from that bow could ever miss its mark. She also dressed him from head to foot in the garb of an ancient warrior, formerly the property of his grandfather, as was the bow. She told him that he had a long, hard road to go, and many trials to overcome; but he was not afraid. All day he travelled, and, at night fall, came to a wigwam in which lived an old man. Wālūt asked him where Tomāquè might be found. The old man answered: “I cannot tell you, my child. You must ask my brother who lives farther on. He is much older than I, and he may know. To-night you can rest here, if you can put up with the hardships of my wigwam.” Wālūt accepted this offer, and the old man began to heap great stones on the fire. It grew hotter and hotter, and Wālūt thought his last hour had come; but he said to himself, “I can suffer,” and he piled more stones on the fire, and built a wall of them about the wigwam, so that it grew hotter than ever, and the old man said, “Let me out, let me out, I am too hot!” But Wālūt said, “I am cold, I am cold!” and so he conquered the first magician.{38}

Next night he came to the home of the second brother, who made the same answer to his inquiries as the first, and also offered him a night’s shelter if he could bear the hardships of the wigwam. No sooner had Wālūt accepted his offer, than he sat down and bade his guest pick the insects from his head and destroy them, after the old custom, by cracking them between his teeth. Now these insects were venomous toads which would blister Wālūt’s lips and poison his blood. Luckily he had a handful of cranberries in his pocket, and for every toad, he bit a cranberry.[6] The old man was completely deceived, and when he thought that his guest had imbibed enough poison to destroy him, he bade him desist from his task. Thus Wālūt passed successfully through the second trial. On the third day he journeyed until he came to the abode of the third brother, oldest of all, seemingly just tottering on the brink of the grave. Wālūt again asked for Tomāquè, and the old man answered: “To-morrow, I will tell you. Rest here to-night, if you can bear the hardships of my home.” As they sat by the fire the old man began to rub{39} his knee, and instantly flames of fire darted from every side; but Wālūt was on his guard, and uttered a spell which drew the old man slowly, but surely, into the fire which he had created, and he perished. “Rub your knee, old man,” cried Wālūt, “rub your knee until you are tired!”

Next morning as he drew the curtain, boom, boom, a noise like thunder fell upon his ear. It was the drumming of a giant partridge. Wālūt fitted an arrow to his bow and shot the bird to the heart, well knowing that it was his wife’s sister “Kākāgūs,” the Crow, who had come to capture him. Towards evening he reached a great mountain towering above a quiet lake. As he looked, he saw upon the summit, his wife, embroidering a garment with porcupine quills, for this was where she lived with her mother. Catching sight of him, she plunged at once into the centre of the mountain, having no memory of her husband. He, however, hid himself, feeling sure that she would come forth again, and being determined to seize her before she could again disappear. Soon indeed he saw her and tried to grasp her, but only caught at her long hair. Instantly,{40} she drew her knife, cut off her hair, and vanished into the mountain, where her mother loudly reprimanded her, saying, “I told you never to go outside; you see now that I was right. Nothing remains but for you to go in search of your hair.” Next day, therefore, the girl set forth, and on reaching the wigwam of the second old man, her grandfather, for all of the old men were of her kin, the veil was lifted and she knew that it was her husband who had sought her and stolen her hair. She at once rejoined him; he restored her long locks, and, by his magic power, they again grew upon her head and for a year all went well. At the end of that time she became the mother of a boy, whom she called “Kīūny” the Otter. Soon all the game and fish disappeared. Wālūt went out every day, searching the woods and waters for many miles around; but, night after night, he came home empty-handed, and starvation seemed very near at hand. Then Nochgemiss, the Grandmother, warned them that Tomāquè was bent on revenge, and bade Wālūt go forth and slay her. She armed him with a bone spear from the old pack kettle, and he travelled to the mountain. It was mid-winter and the{41} lake was covered with clear ice. Deep down beneath the ice a giant beaver swam to and fro, no other than Tomāquè herself. Vainly Wālūt plunged his spear into the depths. Again and again she evaded him, until, in a fury, he cried, “Your life or mine!” and at last succeeded in striking her; but so powerful was she that she raised him into the air, using the spear in his hand as a lever, the other end being deep in her side. The result seemed doubtful; but grandmother, who knew all that was passing, flew to her boy’s aid and, in the shape of a huge snake, Atōsis, wound herself about Tomāquè, fold upon fold, and at last conquered the foe and crushed her to death, Wālūt dealing the final stroke.

Grandmother hastened home, leaving Wālūt unconscious of the help that she had given him, and found Kīūny gasping with fever. His mother, well aware of all that had passed, through the power of second sight, also knew that the baby’s illness was caused by Tomāquè’s dying curse. Meantime Wālūt returned, and his grandmother told him that all she could do, would be to save him; that wife and child must perish, as indeed they soon did.

Not long after, in the early morning, a girl{42} lifted the skin which hung at the opening of the wigwam and looked in. As Wālūt glanced up at her, she fled. He pursued her, but almost instantly lost sight of her. Next day, came another girl, to whom he also gave chase, also in vain. On the third morning, he was more successful, because this time the girl was more willing to be followed. He tracked her to her home, but did not enter, wishing first to consult his grandmother. She told him that these were the three daughters of “Mōdāwes,” or Famine. The youngest girl, she said, would be a good wife to him; and she directed him, when she came next day, to touch her lightly on the arm.

The girl came; he pursued her and, fleet-footed though she was, he managed to touch her before she escaped into her mother’s wigwam. Ere long, to her mother’s rage and fury, but much to the delight of her sisters, a little boy was born to her, who, in reality, was Wālūt endowed with this form by his grandmother’s aid,—no baby, but a strong brave man.

Now, Mōdāwes was a cannibal, and the ridge-pole of her wigwam was strung with cups made from the skulls of her victims. Wālūt, seeing these, was at once aware that they were all that{43} was left of those who had fallen prey to the witch’s horrible appetite. He resolved to slay her; but as her daughters had been very kind to him, he wished to spare them, and said to himself: “I wish that a snow-white deer would pass by!” Instantly, the white deer moved slowly before the door. The three girls sprang after it. Wālūt rose to his full stature; clad in his grandfather’s ancient dress, he snatched his timhēgan from his belt and, with a single blow, laid Mōdāwes dead at his feet. He then set fire to the wigwam and returned to Grandmother Loon. When the three daughters of Mōdāwes gave up their hopeless chase of the enchanted deer and came home, no home was there, only a black heap of ashes. They mourned for their dear baby, whom they naturally supposed had perished in the flames; but they never again found the path which led to Wālūt’s lodge.{44}

OLD SNOWBALL

Many years ago an Indian family, consisting of an old father and mother, their two sons, and their baby grandson were camping in the woods for the winter hunt. In the same neighborhood lived a horrible old witch and her three daughters. This witch ate nothing but men’s brains and skulls. She would pick the bones clean, and dry them, and had a long row of such trophies all round the upper part of her wigwam, looking like so many snowballs. From this she took her name, and was known as old Snowball. The girls were very beautiful, and set out by turns every evening to ensnare some young man for their mother’s meal. So it happened that soon after the Indian family had settled in camp, one twilight, as they sat round the fire, a beautiful girl passed by, so charming the eldest son, that he set out in pursuit of her and never returned, having fallen a prey to Snowball. A night or two later, another equally{45} lovely girl appeared, and the second son, who was a widower, and the father of the baby boy, started to chase her, with the same result. The same fate befell even the old man, and the poor old woman was left alone with the baby. She was terribly afraid that the witch would get him too, and kept him hidden in a great birch-bark basket, t’bān-kāgan. As he grew older and began to talk and run about, he was always wishing that he were a grown man, that he might help his grandmother, hunt for her and fetch in wood for her. At last, the old woman, who was something of a magician, told him that if he really was so anxious to be big, he might lie down that night on the other side of the fire, and she would see what could be done. Next morning, behold, he was a full grown man. His grandmother brought out her husband’s pack kettle, and gave him all the tools and weapons which he needed, stringing his bow with her own hair. Thenceforth, he brought in plenty of game, and they would have been very happy if the old woman had not constantly dreaded the appearance of the witch’s daughter. At last she came, looking more fascinating than ever; but the young man went on with his work, and never{46} raised his eyes. Next night, the second daughter passed by; he looked up at her, but that was all. The third night, the third daughter, youngest and fairest of all, appeared. He sprang up to follow her; but his grandmother begged him to stay, or she would kill him as she had slain so many of his family. He finally consented to wait till another night, and said that he would not chase her, but merely follow and see where she went. His grandmother wept bitterly, but did her best to ward off misfortune, by seeing that he took the bow strung with her hair, and also a certain small bone from the mink, possessed of great magical power. The young man soon turned himself into a tiny bird, “chūkālisq’,” and hopped about almost in reach of the girl’s hand. He seemed so tame that she thought she might lay her hand on him, and indeed after several attempts she did contrive to catch him and put him in her bosom. Then she ran home to tell her mother of the lovely bird that she had found. “That is no bird,” said her mother; “just let me look at him.” She put her hand in her breast, but there was nothing there. From that moment she grew bigger and bigger, and in due time gave birth to{47} a fine boy. Her mother wanted to kill the child; but she would not consent, and, for safe keeping, carried the baby always in an Indian bark cradle strapped over her shoulders. Meantime, the spell of her beauty held possession of the young man, and he could not rest till he saw her once more. Turning himself into a deer, he sought Snowball’s lodge, where he gambolled and played about until the three girls ran out to see the pretty creature, forgetting the baby who had been left behind. The deer led them into the forest, and then sped back to the lodge, where he found the witch just about to kill the child and devour its brains. Taking his spear, he at once slew her and, hiding himself, killed the two older girls in turn as they returned home. When the third daughter appeared, he stepped forward and claimed her as his wife. “Now,” said he, “you must stand aside, for I am going to burn up the lodge with the bodies of your mother and sisters.” She was very unwilling, but at last yielded. The old witch was loath to die, and rose repeatedly from the flames; but the magic spear was too much for her. The young man, with his wife and baby, went home to his grandmother, and for a year lived{48} very happily. Then the young woman became sad and silent and, when questioned, said that great trouble was at hand, that her aunt, who was a powerful sorceress, was coming to avenge the murder of her kindred, and she feared the consequences. The grandmother made all preparations, this time stringing the bow with the young woman’s hair. Next day the baby began to cry, and nothing would quiet him, until the old woman thought of giving him her husband’s bark pack kettle, where some of his ancient treasures were still kept. Then the baby smiled, and began to turn over the things and play with them. Suddenly he laughed aloud and cooed for joy and toddled to his father with a little bone. “Fool that I am,” exclaimed the old woman, “how could I forget that! This may save us yet.” (It was Luz, the ancient resurrection bone of the Jews, and had once formed part of the anatomy of one of the greatest magicians ever known.) The young man bound it to the head of his spear and set forth, his grandmother having told him that the time had come, and that he must that day kill the great Beaver (his wife’s aunt), or the whole family must perish. He soon came to a great{49} lake where there was a beaver dam as high as a mountain. He could see the big Beaver moving about under the ice; but all his efforts to pierce the ice were in vain, it grew thicker and thicker under his spear, and rose in great waves. He returned at nightfall discouraged, but started out again next day, his grandmother tearing apart her scarlet bead-wrought legging, and bidding him fling that on the ice to see if it would not break the charm. All day he strove, but even the legging was of no avail. Next day he took the second legging, and at last succeeded in striking his spear through the ice and into the enemy, Quābīt. Then began a mighty battle, Beaver struggling to break the spear or to escape, and the young man fighting to retain his hold. At home the baby began to scream and cry, and the women knew their hero was in danger. The grandmother wept as if her boy were already dead; but his wife said, “Fear not, for I will help him.” She flung a handful of magic roots out at the door, and instantly a sheet of water lay there, and she was at her husband’s side. She told him not to loose the spear, but to watch well, that she would fight his battle. “If you see me pass under the ice{50} before my aunt, all is well; but if she comes first, she has conquered, and we must all perish. I shall be all white like snow, while she is jet black.” The young man stood rooted to the spot, while the ice cracked and heaved with fearful noises. At last the white beaver passed before him under the clear ice, and he knew that victory was his. His wife then told him that there was still another and a more terrible enemy to be conquered before he and his could be safe. This triumph too she gained, though at a fearful cost, for she was never again to see her husband, home, or child. The young man went back to his grandmother with drooping head, and heard how the baby had kept his grandmother informed of the progress of the fight by his changing tears and smiles. And that is all about it.{51}

ĀL-WŪS-KI-NI-GESS, THE SPIRIT OF THE WOODS

Seeing a smoke come from the top of a mountain, the children asked the elders what it was, or who could live there, and the fathers told them: “That is the home of ‘Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess,’ a tree-cutter, whose hatchet is made of stone. He throws it from him; it cuts the tree and returns to its master’s hand at each blow. One stroke of his hatchet will fell the largest tree. No one ever saw him save Glūs-kābé, who often goes to the cave to visit him. He is a harmless creature, and only fights when ordered to do so by Glūs-kābé. He lives in that mountain, on deer, moose, or any meat he can kill. Sometimes he goes out to sea with Glūs-kābé, to catch ‘K’chī būtep,’ the Great Whale.

“ ‘Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess and ‘Kiāwāhq’ once had a big fight, which lasted for two days. Kiāwāhq’ put forth all his power to conquer, but failed. He uprooted huge trees, expecting them to{52} fall and crush his rival in strength; but Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess would hurl his hatchet and split the tree asunder. Kiāwāhq’ strove to drag him into the sea, but the wood spirit is as strong in the water as on land, to say nothing of the fact that when he is in the water, ‘K’chīquī-nocktsh,’ the Turtle, comes to his aid. Once Kiāwāhq’ got his foe between two great trees and felt sure he could slay him as they fell. Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess seized his axe and struck the trees which fell. The wind caused by their fall was so mighty that it left Kiāwāhq’ faint and exhausted. He was forced to beg for quarter, and promised his enemy that if he would spare his life, he would give him a stone wigwam and be his good friend forever. So the wood spirit had mercy and accepted his offer. That is how he got that cave where he still lives.”

This was the answer of the elders to their children’s question.{53}

M’TEŪLIN, THE GREAT WITCH

In a certain place, alone by herself, lived an old woman whom none dared to approach, for she had bewitched many Indians.

In the spring of the year when the men came back from their long winter hunting for furs, they would gather together and build what they called eqū’nāk’n,[7] hot-baths, to drive off their diseases. They would enter the hut, and heat it red-hot until it would almost roast them. They would strip off their clothes, and dance and sing songs to drive off disease.

Once before the performance ended, they were amazed to see a woman among such a crowd of men; but they feared to speak to her. One young man laughed when she threw off her clothes. This angered her, and she said: “You laugh at me now; but I will send a flood to destroy you.” Then she left the hut.{54}

After a time, the youth who had laughed, said, “Hark!”

All stopped to listen, and they heard the rush of water, and knew the witch had kept her word,—the flood was upon them. But the young man was something of a sorcerer too, and had a rattlesnake for poohegan, or messenger (all witches have at least one poohegan).

He instantly changed all his comrades into beaver and fish.

“Ha! ha!” laughed “Copcomus,” Little One, for such was the youth’s name. “You cannot finish your work, old witch. I will be avenged on you yet. I will pray Glūs-kābé to follow and kill you.”

They all swam out of the eqū’nāk’n, and when the water ceased to flow, Copcomus went along the stream and saw a large number of beaver building a house like eqū’nāk’n, so he changed them all back to Indians again. They were very glad, and thanked him heartily.

“Now,” said Copcomus, “we must hold a council at once and decide what to do with the old witch, for she will try to destroy us yet.”

Some said, “We will burn her wigwam;” one said: “No, she would know of our coming{55} and turn us into some evil thing!” Another said his idea was to persuade the great bird, Wūchowsen, Wind, to move his wings harder and faster, thus causing “Uptossem,” the Whirlwind, to destroy her; but Copcomus said: “I will see to-night what is best.” (Witches always see in their sleep how their enemies may be destroyed).

The old woman too saw in her sleep that Copcomus was plotting to kill her; so she sent her messenger, the Humming-bird, to bid Wūchowsen not to move his wings faster than usual.

Copcomus cried to his poohegan: “Go, creep into her wigwam and bite the old witch;” and he tied cedar bark about the snake’s rattle, that it might make no noise.

The snake went by night, glided in and bit the old woman’s big toe. The pain waked her, and her toe swelled rapidly. She sent the Humming-bird to seek Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess, the Wood Spirit.

The bird flew to the cave in the mountain, and when Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess asked: “How now, little bird?” the bird replied: “The Great Witch bids you come with your hatchet without delay.” So the Spirit lit his pipe and set forth. When{56} he reached his journey’s end, he found the witch moaning with pain. “What is the matter, ‘Mookmee’ [Grandma]?” he asked.

Her only reply was: “Cut off my toe at once.”

He raised his axe, but K’chīquīnocktsh, the Turtle, Glūs-kābé’s uncle, who had been sent by Glūs-kābé to help Copcomus, jogged his elbow and the hatchet cut off her leg.

Next day Copcomus said to his men: “We must go and implore Glūs-kābé to conquer the witch. No one else can do it.” So they besought the mighty Master to help them. He laughed aloud, and said: “What! all these strong men with warclubs, spears, and bows, to slay one poor old woman! Why, my uncle could do the work single-handed.”

“She must die,” said Copcomus; “we will send your uncle, the Turtle, and let him do the work single-handed.”

So the Turtle set forth once more; but as he is a slow traveller, it took him two days to reach the witch’s home. “What is the matter, Grandma?” he asked. “Alas!” she cried, “Āl-wūs-ki-ni-gess has killed me!”

Turtle then drew his hunting-knife and finished her.{57}

SUMMER

There lived near “Kīsus,” the Sun, a beautiful woman named “Niffon,” Summer. She dressed in green leaves, and her wigwam was decked with leaves and flowers of many different sorts. Her grandmother, Sogalŭn, Rain, lived far away, but when she visited her granddaughter, she always warned her never to go near “Let-ogus-nūk,” the North, where her worst enemy, “Bovin,” Winter, lived, saying: “If you do go, you will lose all your beauty, your dress will fade, your hair will turn gray, and your strength will leave you.”

But Niffon paid no heed to her grandmother’s warning. One fine morning as she sat in her wigwam gazing northward, and saw no signs of Bovin,—the sun was shining and she could see for a long distance,—a beautiful region lay stretched before her, broad rivers, and lakes, and high mountains,—something within her bade her go forth to see that strange{58} country; so she started on her long journey. She knew that her grandmother could not see her, and though she seemed to hear her say: “Do not go near your enemy; he will surely slay you,” she did not heed it, but journeyed on and on. The mountains and lakes seemed far away; but she did not lose heart. Looking back, she could see nothing of her own lovely home. The bright sun overhead was the only thing not new and strange to her. She felt a vague sadness and distress; and when once more a voice murmured: “Do not go, my daughter,” she resolved to turn back, but it was too late. Some unseen power now forced her towards the north. Still the mountains and lakes were as far away as ever; her dress was beginning to fade; her long hair had turned gray; her strength was failing fast; the sun, too, had lost his power; and, as she neared her journey’s end, she saw that the mountains were but heaps of snow, the beautiful lakes but fields of ice.

Meantime her grandmother, seeing no smoke rise from Niffon’s wigwam, grew alarmed and concluded to visit her. When she got there, she found the wigwam empty, the green boughs on the floor withered and dry, and the leaves{59} faded. “Oh, my poor grandchild is in the clutches of Bovin,” she cried, and summoned her bravest warriors, “Sūwessen,” the South Wind, “Hy-chī,” the East Wind, and “Snoteseg-du,” the West Wind, and bade them hasten northward and fight like devils to save Niffon.

These invisible warriors started on their journey, and as they did so, Bovin felt that something was wrong, and ordered his braves, “Letū-gessen,” North Wind, and “K-lkegessen,” Northeast Wind, to hurry southwards and meet the foe.

Sweat began to pour from Bovin’s every limb, his nose grew thin, and his feet shrivelled away. Another day and the giants met; large flakes of snow mixed with raindrops flew in every direction; sharp gusts of contrary winds were heard. The drops of sweat on Bovin’s brow grew larger and larger. By this time, the hair on Niffon’s head was snow white and her dress tattered and faded.

The roar of the wind grew ever louder and sharper; the snow and rain fell faster and thicker; at last Bovin fell from his place and broke one of his legs, and Niffon knew her enemy was conquered.{60}

Bovin bade one of his warriors tell Niffon to depart; he will harm her no more.

Then she turned again towards her own country, her beauty all gone, an old old woman.

Many hours pass; by degrees, as she travels her strength returns, she moves faster, and, as the air grows warmer and softer, she feels happier and begins to look young again; her hair returns to its natural color, her dress is green once more. She sees the lakes and rivers shining; but it will still be many days before she reaches her wigwam, and she must meet her grandmother before she sees her dear home.

At last the air was warm, the clouds grew dark, the rain began to fall, and the wind blew fiercely; amidst the darkest clouds she saw a large wigwam; she entered and found her grandmother reclining on a bed of skins, so changed that she hardly knew her.

The old woman looked up and said: “My child, you have nearly caused my death. I have lost all my power through your disobedience. I can never help you in your future wars. My great fight with Bovin has taken all my strength; go and never depend upon me more.”{61}

THE BUILDING OF THE BOATS[8]

When the water was first made, all the birds and the fowl came together to decide who should make their canoes for them, so that they might venture out upon the water.

The Owl proposed that the Loon should do the work; but the Black Duck said: “Loon cannot make canoes; his legs are set too far behind. Let the Owl make them.”

Then the Loon said: “The Owl cannot make canoes; his eyes are too big. He can’t work in the day-time for the sun would put out his eyes.”

Then the Duck laughed and made fun of the Owl. This made the Owl angry, and he said to Black Duck: “You ought to be ashamed of your laugh; it sounds like the laugh of ‘Kettāgŭs,’[9] quack, quack, quack.”

Then all the fowls laughed aloud at the Duck.{62} The Owl said: “Let ‘Sīps’ [the Wood Duck] build our boats.”

“How can he build canoes,” cried all the rest, “with his small neck?”

“He is too weak,” said the Loon.

The birds were quite discouraged; but they liked the looks of the water very much. At last “Kosq’,” the Crane, spoke: “My friends, we cannot stay here much longer. I am very hungry already. Let us draw lots, and whoever draws the lot with a canoe marked on it shall be the builder of boats.”

All were satisfied with this suggestion, and the Raven was appointed to prepare the lots; but the Owl objected, saying: “He is a thief; I know he is.”

“Well,” said the Night Hawk, “let us get Flying Squirrel to make them.”

“But Flying Squirrel is not here.”

“Well, let some one go for him.”

“Well, let us get Fox to go for him,” said the Loon.

“Oh! I can’t trust the Fox to go,” said the Owl; “for he would eat Squirrel on the way. Just let me give you a word of advice. Let Āfiguessis [Little Mouse] go for the Squirrel.”{63}

“Yes,” said K’chīplāgan, Eagle, the great chief, “we must do as he proposes. Come, Āfiguessis, you must go for the Flying Squirrel.”

When they saw the Squirrel coming, all cried: “Room! Make room for him!”

Then the Squirrel stood up before the chief and asked: “What can I do for you, my friends?”

Eagle told him that they wanted him to make a picture of a canoe on birch bark with his teeth; to make many more pieces all alike; then to put them in his “miknakq,”[10] and let each bird take one. “Whoever gets the piece with the canoe on it, shall make our canoes.”

The Squirrel went at once and stripped the bark from a birch-tree, prepared the lots, and put them in his pouch.

“Who takes the first?” asked the Owl.

“Let ‘Mid-dessen’ [Black Duck] take the first,” said the chief.

Mid-dessen stepped forward, and came back with a piece of bark in his bill. So each one went in his turn, and the lot fell to the Partridge.

Now the Partridge is always low-spirited and{64} hardly ever speaks a word; and this set all the other birds in an uproar, and they all sang songs, each after his own fashion, and they decided to have a great feast.

“Get the horn,” said the chief. When it was brought, he gave it to Sīps, the “mū-ta-quessit,” or dance-singer; then the big dance began, and it lasted for many days.

When the feast was over, the chief said: “Now, Partridge, you must make the canoes, sound and good, and all alike. Cheat no one, but do your work well.”

The first one made had a very flat bottom; this he gave to the Loon, who liked it much. The next, flat bottomed too, was for Black Duck; then one for Wābèkèloch, the Wild Goose. This was not so flat.

Another was for Crane. It was very round. The Crane did not like his boat, and said to Eagle: “This canoe does not suit me. I would rather wade than sit in a canoe.”

The Partridge made canoes for all the birds, some large, some small, to suit their various size and weight. At last his work was done. “Now,” said he to himself, “I must make myself a better canoe than any of the rest.” So{65} he made it long and sharp, with round bottom, thinking it would swim very fast.

When it was finished, he put it in the water; but, alas, it would not float; it upset in spite of all that he could do. He saw all his neighbors sailing over the water, and he fled to the woods determined to build himself a canoe.

He has been drumming away at it ever since, but it is not finished yet.{66}

THE MERMAN

In a large wigwam, at the bottom of the sea, lived “Hāpōdāmquen,” the merman. He had two sons and three daughters. The elder son “Psess’mbemetwigit,” Flying Star, was very brilliant and held a lofty position; while the younger “Hess,” the Clam, was the laziest and slowest of the family.

The daughters were named “T’sāk,” Lobster, “Hānāguess,” Flounder, and “Wābè-hākeq’,” White Seal.

Every morning the old man gave orders to his children as to where they should go, and what they should do, warning them against his two mighty enemies, “Lampeguen,” another species of Merman, and Water Witch.

One day as they were about to go hunting, Flying Star told his brother of a fearful dream that he had had the night before. He dreamed that he and his brother were in a large stone canoe, moving swiftly towards the steep running{67} water (falls), when the canoe turned over, and they both went to the bottom of this great “Cobscūk,” cataract. They were surrounded by singular beings, whose chief took a “wūs-āp-gūk” (rawhide), and tied their arms and legs together, then carried them to a strange village, where his warriors held council as to what should be done with the sons of Hāpōdāmquen. It was decided to kill them at once, as the best means to destroy the foe, for without Flying Star, Hāpōdāmquen must surely starve. They decided that the older son should be slain by “M’dāsmūs” (a mythical dog, very large and fierce), and the younger by a war club. Just as they loosed M’dāsmūs, Flying Star awoke.

Upon hearing this dream, Hess at once repeated it to his father.

Old Hāpōdāmquen knew at once that “Āglōfemma,” the chief of the “Lampegwinosis,” was about to attack him. He told his children to watch well, and stand their ground as long as a breath of life remained. To each he gave careful directions: Flying Star was to take up his position in the clouds, and thence watch the sea; if he saw any strange commotion,{68} or heard any strange noise, he was to fly from the clouds to the sea, and kill everything that rose to the surface.

Hess, the Clam, was to post himself in the mud at the bottom of the sea, and was told that Hāpōdāmquen would leave his pipe in the north side of the wigwam. If the contents of the pipe were undisturbed, his children might know that he still lived; but if the “nespe-quomkil,” willow tobacco, were gone, and the pipe was partly filled with blood, they might know that he was dead.

“Go, Hess,” the old man commanded, “bury yourself in the mud, five lengths of your body, and listen well. You will surely hear when the battle begins. Do not try to escape, or you will perish.”

T’sāk, the Lobster, was to take up her station half-way between the surface and the bottom, and was cautioned not to rise to the surface at any time.

Hānāguess, the Flounder, was ordered to come to the surface, where she was to watch and follow the little bubbles; for when her father left his wigwam, the bubbles would rise to the top of the water.{69}

Wābè-hākeq’, the White Seal, was the bravest and brightest of the Hāpōdāmquen family; she was to accompany her father to the land of the Lampegwinosis.

The old man knew that only the chief and a handful of men would be in the village; the fiercest warriors would be lying in ambush for his two sons at the falls, where Flying Star and Clam always went to spear eel. If Hess had failed to tell his father of Flying Star’s fateful dream, even now they would both be suffering torture at the hands of the foe. As it was, the old man and his brave daughter would attack the village by night, while the enemy slept and dreamed of battle and war.

Hāpōdāmquen always wore his hair very long, streaming behind him three times the length of his body. As they neared the village, he felt something heavy clinging to his hair,—it was tiny beings, as small as the smallest insect, the poohegans, or guardian spirits, of the chief of the Lampegwinosis, little witches who tried by their combined weight to lessen the old man’s speed, so that they might gain time to warn their master of the enemy’s approach.

The Lampegwinosis were taken entirely by surprise;{70} the strongest men were away, only the old and weak were at home. The great army of Hāpōdāmquen, composed of all the lobsters, seals, flounders, and clams, was at hand, and the battle began. It was a fearful fight, lasting for two days and nights. The Lampegwinosis chief tried to escape to the surface; but the waves rose mountain high, and he was always driven back by the watchful Flounder.

Flying Star slew all those warriors who reached the surface; while White Seal attacked the tiny witches, putting forth all her magic power before she succeeded in subduing them. Then she went to her father’s aid. He was almost exhausted; but she directed her sister, the Lobster, to bite the hostile chief in his tenderest part, and hang to him until the White Seal could put an end to him. T’sāk held on, and White Seal killed the foe with one blow of her battle-axe. This ended the conflict.

Hess remained in the mud, where, from time to time, he heard his father encouraging his men. When all was still once more, he crawled out and went to his father’s wigwam. He was so glad to find the pipe undisturbed, that he sang a song of peace.{71}

Hāpōdāmquen ordered his warriors to return to their homes until he should again summon them; and he went back to his wigwam, where he found his lazy son, Clam, still singing.

All the bubbles and foam had vanished from the sea. Flying Star and Flounder, coming home, found their father happy, though badly hurt, for he had lost all his beautiful hair in the fight.

As the Lampegwinosis braves wended their disconsolate way back from the falls, they saw their old Chief-with-feathers-on-his-head borne off by an animal resembling an otter, whom they recognized as Hākeq’, the brave daughter of Hāpōdāmquen. They moaned for their chief; but Hāpōdāmquen still lives to destroy little children who disobey their mother by going near the water.{72}

STORY OF STURGEON

“This story,” said old Louisa, “is from ’way, ’way back, ever so long ago;” and indeed it seemed to me that it was so old that only fragments of it remained; but I give it as best I can.

Many, many years ago there were three tribes of Indians living not far apart: the Crows, Kā-kā-gūs, the Sturgeons “Hā-bāh-so,” and the Minks, “Mūs-bes-so.” These tribes were all at war, one with the other, and the Minks, being very crafty and cunning, as well as brave, at last conquered the other tribes, and drove them forth in opposite directions.

Now the followers of Kā-kā-gūs found their way to a dry and desert region where they died of hunger and thirst; the tribe of Hā-bāh-so found plenty of food, but were overtaken by a pestilence which destroyed all but the old chief and his grandson. Meantime, the Minks found that the game had been expelled with the enemy, and they suffered greatly from hunger.{73}

Old Sturgeon, as I said, had enough and more than enough to eat. He and his grandson built an “āgonal,” a storehouse of the old style, which they filled to overflowing with smoked fish and dried meat.

Mink, hearing of this, sent a messenger to investigate. He was well received, and fed with the best. The Mink himself determined to pay the old man a visit, knowing that enemy though he was, he would be kindly treated while a guest, according to Indian etiquette. He asked Sturgeon where he got all his supplies, and was told that they came from the far north. Then he said, “Are you alone here?” “Yes,” said Hā-bāh-so, “except my grandson;” pointing to a huge Sturgeon who lay flopping by the fire.

Next day when Mūs-bes-so left, he was loaded with as much meat as he could carry. When he got home, he told his story, and suggested to his five daughters that one of them should marry Sturgeon’s grandson, who would keep them in plenty for the rest of their lives. So the girls set out to visit the enemy in turn, and each returned saying, “I would not think of marrying that monster. If ever I marry, I shall choose a man, and not a fish, for a husband.”{74} So it went until it came to the youngest girl. She entered Sturgeon’s wigwam and, without a word, made herself at home, began to arrange the bed and cook the food. When night fell, and she did not return, her father rejoiced, for he knew she had married young Sturgeon.

She, meantime, had waked at night to find a handsome youth beside her, who, with the first rays of daylight, again became a fish. They were very happy together and knew no care. Every morning she found a supply of the choicest game or fish at the door, and in due time she became the mother of a lovely boy.

Her husband proposed to visit her family to exhibit this new treasure, to which she gladly acceded. He told her that there was but one difficulty; namely, that she would have to carry him as well as the baby. She made no objection, and they set forth. When they were almost in sight of the Mink village, the young man was turned to a big Sturgeon, which his wife shouldered, taking the baby in her arms.

The old Minks were delighted to see her; but the sisters laughed and sneered at Sturgeon, and despised their sister for being willing to accept such a husband. They were very glad, nevertheless,{75} to accept the supplies of food which he provided every day; and their contempt was turned to envy when they awaked one night and saw him in his human form. They then began to plot how they might kill their sister and take her place; but Sturgeon, learning their plans, comforted his distressed wife, promising to punish her wicked sisters, whom he did indeed turn into turtles, in which condition they led a moist and disagreeable life.

After this, he felt that it was time for him to go; so he furnished his father-in-law with enough provisions to last a year, and set forth on his return journey with his wife and son.

Before they had gone far, they saw in the distance Kosq’, the Heron, coming towards them. Now Kosq’ had been a suitor of Mistress Mink before she married Sturgeon, and the latter knew him to be bent on vengeance. He told his wife that she must help him, for Kosq’ had great power, and it would not be easy to overcome him. Together they built a circular wigwam, in which they shut themselves, Kosq’ prowling about outside, each determined not to stir from the spot until the other yielded to starvation.{76}

Mistress Mink dug in the earth at one side of the wigwam, the bed being on the other side, and the fire-place in the middle. She dug until a stream of water flowed forth which not only gave them drink, but which contained various insects and small creatures which satisfied their hunger.

Kosq’ outside dug with his long bill and found little or nothing, this inner stream attracting all upon which he otherwise might have fed. So he flew thither and thither, weaker and weaker, and ever and again he cried to Hā-bāh-so: “Will you give up, now?” “No, no,” was the reply; “I am strong and well.”

Finally, poor Kosq’, determined not to yield, died of sheer hunger, and Hā-bāh-so, with his brave wife and child, came from the wigwam, went back to their old grandfather, and in time built up a village.{77}

GRANDFATHER KIAWĀKQ’

As I was sitting with old Louisa I showed her an African amulet which I was wearing, made of pure jade, inscribed with cabalistic characters to ward off the evil eye. Thinking to make it clear to her Indian understanding, I told her that it was to keep off m’tēūlin, sorcerers, and kiawākq’ (legendary giants with hearts of ice, and possessed of cannibalistic tastes). She looked very grave, and told me that I did well to wear it, for there were a great many kiawākq’ in the region of York Harbor where we were; it was a famous place for them, although they usually chose a colder place, somewhere far away, where it was winter almost all the year. This subject once started, she went on to tell me of an adventure of her father.

Years ago when he was first married, and had but one child, a boy about two years old, it was his habit to go with his family, in a canoe, in{78} the late autumn, and camp out far up north in Canada, in search of furs and skins for purposes of trade. He would build a large comfortable wigwam in some convenient place, and stay all winter. One year, while hunting, he came across a deep footprint in the snow, three or four times as large as that of any man. He knew it was the track of a kiawākq’, and in terror retraced his steps, and thenceforth carefully avoided going in that direction. In spite of this precaution, however, the creature scented him out; for while he was away from the lodge, a huge monster entered, stooping low to enter, and making himself much smaller than his natural size, as such creatures have the power to do. The poor woman, alone there with her child, knew him for what he was, and knew that her only hope of escape lay in hiding her fear, so she addressed him as her father, and offered him a seat, telling the little boy to go and speak to his grandfather. She cooked food for kiawākq’, warmed him, and paid him every attention. When her husband returned, she said to him that her father had come to visit them, and he, too, welcomed the monster, who remained with them all winter, going out to hunt,{79} and bringing back moose, bear, and other big game, which the man dressed for him. He seldom spoke; but she often saw him look greedily at the baby, and sometimes he would put one of the boy’s fingers in his mouth, as if he could not resist the temptation to bite off the dainty morsel; but he always let the little fellow go unharmed at last. It was no use for the family to think of escape, as he could so easily have overtaken them; and, if angered, they knew that he would destroy them.

Towards spring he told them that the time had come for them to go. He said that his little finger told him that another and mightier kiawākq’[11] was on his way to fight with him. “You have been good to me,” he said, “and I wish to save you. If my enemy conquers me, he will destroy you; so you must go now, before he sees you. If I live, I will come to your village.”

So the man with his wife and child got into the canoe and paddled away. After a while they heard the other kiawākq’ coming afar off, for he tore up great trees as he came and flung{80} them about like straws, and uttered terrible roars. Then they heard the noise of the awful fight; but fear lent speed to their canoe, and they at last lost all sound of the dreadful kiawākq’.

They never saw their big friend again, and therefore felt sure that he had perished; but they never dared to go back to that camping ground again.

“So you see,” said Louisa, “that the kiawākq’ really saved the life of my family.”[12]

OLD GOVERNOR JOHN

All summer I had not succeeded in coaxing a single story out of Louisa; but last week she said, “You come Sunday, I tell you a story.” This seemed to be because I told her I was going away. Sunday, when I took my seat in the tent, she said, looking very hard at me, “This is a true story; it is about her great, great grandfather,”[13] pointing to her daughter Susan, “Old Governor John Neptune. He was a witch.” I had often heard from other Indians tales of old Governor Neptune’s magic powers. “He was such a witch that all the other witches (m’tēūlin) were jealous of him, and they tried to beat him. He fell sick, and he could not lift his head; so he said to his oldest daughter (he had three daughters), ‘Give me some of your hair.’ She did so, and he bound his arrowheads and spear with it, and strung his bow with the{82} long, strong black hair. Pretty soon the earth began to heave and rock under him. His daughter told him of it, and he took his spear and stuck it into the ground just where it was beginning to break. He thrust it in so deep that his arm went into the earth up to the elbow, and when he drew it out the iron was bloody. ‘Now I feel better,’ he said; and he sat up, took his bow and shot an arrow straight into the air. Then he told his old lady to make ready and come with him, but not to be afraid. They went to Great Lake; he told her again not to be scared, took off all his clothes, and slipped into the lake in the shape of a great eel. Presently the water was troubled and muddy, and a huge snake appeared. The two fought long and hard; but at last the old lady saw her husband standing before her again, smeared with slime from head to foot. He ordered her to pour fresh water on him, and wash him clean, for now he had conquered all his enemies. From that day forth they had great good luck in everything. This was in his youth, before he became governor of the Indians of Maine.

“One time in midwinter his wife had a terrible longing for green corn, and she told him. He went to the fireplace, rolled up some strips of{83} bark, laid them in the ashes, and began to sing a low song. After a while he told her to go and get her corn, and there lay the ears all nicely roasted. He used to make quarters, too. He would cut little round bits of paper, put them to his mouth, breathe on them, then lay them down and cover them with his hand. By and by he would lift his hand with a silver quarter in it.” I remarked that he ought to have been a rich man; but Louisa said, “Oh, he didn’t make many, just a few now and then. When he was out hunting in the woods with a party and the tobacco gave out, they would see him fussing round after they went to bed, and then he would hand out a big cake of tobacco.”

Louisa said several times, as if she thought me incredulous, “This is a true story; the old lady told me about the corn herself, and she was the mother of my brother Joe Nicola’s wife. She was a witch, too.”

I asked Louisa when and how the Indians learned to make baskets and she said they always knew. When Glūs-kābé went away, he told the ash-tree and the birch that they must provide for his children; and so they always had, by furnishing the stuff for baskets and canoes.{84}

K’CHĪ GESS’N, THE NORTHWEST WIND

When he was a baby he was stolen by “Pūkjinsquess,”[14] and taken to a far-off lonely country inhabited by invisible people. His first recollection was of lying under the “k’chīquelsowe mūsikūk,” or frog-bushes.[15]

He rose, and, seeing a path, followed it until he reached a wigwam. When he lifted the door, he saw no one, but heard a voice say: “Come in, ‘nītāp.’ ”[16]

He went in, and the voice said: “If you will be friends with me, I will be friends with you, and help you in the future.”

He looked about him, but saw nothing but a little stone pipe. He picked it up, and put it in{85} his bosom, saying: “This must be the one who spoke to me.”

Then he went out and followed the path still farther. He heard the cry of a baby, so he hid behind a tree. The sound came nearer. Soon he saw a hideous old woman with a baby on her back, which she was beating. This roused his temper, and he shot her with his bow and arrow. She proved to be Pūkjinsquess, and the baby was his brother, whom she had stolen from his father, the great East Wind.

He put the baby in his bosom, and kept on his way. The baby said to him: “There is a camp ahead of us, but you must not go in, for the people are bad.”

To this he paid no heed; and when he came to a large, well-built wigwam, he was eager to see who the bad folks were. He found a crack, and looking through it, he saw a good looking man, with cheeks as red as blood, who said: “Come in, friend.”

They talked and smoked for some time; then the strange man, whose name was Sūwessen, the Southwest Wind, said: “Let us wash ourselves and paint our cheeks.” They did so, and then kept on talking; but every few moments the{86} good-looking man would start up and say: “Let us wash ourselves.”[17]

In the evening two beautiful girls (daughters of Southwest Wind) came in and began to make merry with them; but this tired the Northwest Wind, and he fell asleep. As soon as he was sound asleep, Sūwessen took a long pole and tossed him like a ball,[18] saying: “Go where you came from.”

At this, the Wind woke and found himself at the same point from which he had started as a baby. Angry and discouraged, he felt in his bosom to see if the stone pipe and his brother were safe; and finding them there, he threw them on a big rock, and killed both in his rage. Then he resumed his journey, but took a different course. He now travelled towards the east, where his father lived.

As he crossed a hill, he saw a lake shining in the valley below. He turned towards it; but before he reached it, he came to a much travelled path, which led him to a wigwam, on entering{87} which he saw a very old woman. She cried: “Oh, my grandchild, you are in a very dangerous place. I pity you, for few leave here alive. You had better be off. Across the lake lives your grandfather. If you can swim, you may escape; but be sure, when you near the beach, to go backward and fill your tracks with sand.”

He did as she directed; but as he approached the water, he heard a loud, strange sound, which came nearer and nearer. It was the great M’dāsmūs, the mystic dog, barking at him.

He plunged into the water, thus causing M’dāsmūs to lose the trail and give up the chase.

Northwest Wind went back to his grandmother; but she avoided him, saying: “You are very wicked; only a few days ago, I heard news in the air, that you had killed your brother, also your friend, the Little Stone Pipe.”

Once more he plunged into the lake, and this time reached the farther shore in safety. There he found his grandfather, “M’Sārtū,” the Eastern Star. (The Indians believe this to be the slowest and clumsiest of all the stars.)

The great M’Sārtū welcomed him: “My dear grandson, I see that you still live; but you are very wicked. I hear in the air that you have{88} killed your brother, also your friend, the Little Stone Pipe. I also hear that you have lost your Bird ‘Wābīt’ and your Rabbit. But, my child, you are in a most perilous place. The great Beaver destroys anything and everything that comes this way. If you need help, cry aloud to me. Perhaps I can aid you.”