Sheer Off.

A. L. O. E. BOOKS,

35 Volumes, Uniform—90 cents each.

| Claremont Tales. | ¦ | Robber's Cave. |

| Adopted Son. | ¦ | Crown of Success. |

| Young Pilgrim. | ¦ | The Rebel Reclaimed. |

| Giant-Killer, and Sequel. | ¦ | The Silver Casket. |

| Flora; or, Self-Deception. | ¦ | Christian Conquests. |

| The Needle and the Rat. | ¦ | Try Again. |

| Eddie Ellerslie, etc. | ¦ | Cortley Hall. |

| Precepts in Practice. | ¦ | Good for Evil. |

| Christian Mirror. | ¦ | Christian's Panoply. |

| Idols of the Heart. | ¦ | Exiles in Babylon. |

| Pride and his Prisoners. | ¦ | Giles Oldham. |

| Shepherd of Bethlehem. | ¦ | Nutshell of Knowledge. |

| The Poacher. | ¦ | Sunday Chaplet. |

| The Chief's Daughter. | ¦ | Holiday Chaplet. |

| Lost Jewel. | ¦ | Children's Treasury. |

| Stories on the Parables. | ¦ | The Lake of the Woods. |

| Ned Manton. | ¦ | Sheer Off. |

| War and Peace. | ¦ |

"Franks had but an instant to try to save him by

catching at the rein, as the maddened hunter rushed like a whirlwind by."

FRONTISPIECE.

SHEER OFF.

A Tale.

BY

A. L. O. E.

AUTHOR OF "CLAREMONT TALES," "GIANT-KILLER, AND

SEQUEL," ETC.

NEW YORK:

ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS,

530 Broadway.

1870.

CONTENTS.

| Page | ||

| I. | The First-Born, | 7 |

| II. | The Falling Almshouses, | 16 |

| III. | The Curate's Visit, | 28 |

| IV. | Joyous and Free, | 36 |

| V. | An Appeal, | 45 |

| VI. | The Return, | 56 |

| VII. | Brightness and Gloom, | 64 |

| VIII. | Pleading, | 73 |

| IX. | The Invitation, | 83 |

| X. | A Happy Home, | 99 |

| XI. | Temptation, | 105 |

| XII. | Ice Below, | 114 |

| XIII. | The Return Home, | 126 |

| XIV. | Norah's Story, | 134 |

| XV. | Norah's Story Continued, | 147 |

| XVI. | Passing Events, | 159 |

| XVII. | Perilous Peace, | 167 |

| XVIII. | Self-Reproach, | 178 |

| XIX. | The Test, | 182 |

| XX. | The Momentous Question, | 190 |

| XXI. | An Old Letter, | 203 |

| XXII. | Peace from Above, | 215 |

| XXIII. | The Wife's Resolve, | 222 |

| XXIV. | The Blind Maiden, | 233 |

| XXV. | Honorable Scars, | 243 |

| XXVI. | A Scrap of News, | 255 |

| XXVII. | Nancy's Return, | 263 |

| XXVIII. | A Search, | 275 |

| XXIX. | Pleasure or Principle? | 283 |

| XXX. | Found at Last, | 289 |

| XXXI. | The Baronet's Return, | 299 |

| XXXII. | The Bonfire, | 308 |

| XXXIII. | Watching for Souls, | 318 |

| XXXIV. | Put to the Question, | 324 |

| XXXV. | Village Talk, | 335 |

| XXXVI. | A Struggle, | 343 |

| XXXVII. | The Sudden Summons, | 350 |

| XXXVIII. | Conclusion, | 362 |

I.

The First-Born.

"Why, there are the church-bells a-ringing! as if it wasn't enough to have all the school-boys going in procession with their garlands, and nosegays, and nonsense!" exclaimed Nancy Sands, the wife of the Clerk of Colme, as she stood in the shop of Ben Stone the carpenter, with her arms a-kimbo, and an expression anything but amiable upon her flushed face. "One might fancy that our new young baronet was a-coming home, or bringing a bride, or that the queen and all the royal family were a-visiting Colme, instead of this fuss being for nothing but the christening of a school-master's brat!"

"Ned Franks is a prime favorite with all the village," observed the stout, good-humored carpenter, as he went on with his occupation[Pg 8] of planing a bit of mahogany, which his visitor wanted for a shelf in her cottage.

"A broken-down sailor, with only one arm!" exclaimed Nancy, with a snort of disdain.

"But with a good head and a better heart," observed the carpenter. "Ned Franks manages so well to keep his lads in order without thrashing them, that one arm is one too many for all that they need in that way. Not but that the wooden affair which I knocked up for him myself, with an iron hook for fingers and thumb, might serve well enough on a pinch to knock a little wit into a blockhead, if that were Ned Franks's fashion of teaching," added Ben Stone with a little chuckle.

"Teaching! he has no more learning in him than my mangle," muttered the scornful Nancy.

"But, like your mangle, he has a wonderful knack of getting things smooth and straight. I don't know what we'd have done in Colme without him, now our poor vicar has been tied up so long; it's Ned as has kept everything going like clockwork. Of course the young curate isn't just at once up to the ways of the place, letting alone that he looks as [Pg 9] young as a boy, and as shy as a girl; he does his best, no doubt, but he couldn't get on without Ned Franks showing him the ins and outs of everything."

Nancy gave another contemptuous snort, but without specifying for whom it was intended. Ben Stone went on with his planing of the shelf and his praise of the school-master, his hand having a very different effect from his tongue; for the more he planed, the smoother grew the wood; while the more he praised, the rougher grew the temper of Nancy. Ben Stone saw this, and took a little malicious pleasure in stirring up the envy and jealousy of his customer; for, though he was not one to break the peace himself, and had never been known to be either out of spirits or out of temper, Ben Stone was certainly not a man to be reckoned amongst the peacemakers. He rather enjoyed "poking the fire in a neighbor's grate," as he once jestingly observed to his wife, and there was always plenty of dry fuel in Nancy's.

But why should praise of Ned Franks be as gall and wormwood to the clerk's wife, seeing that the one-armed sailor, now school-master at Colme, had never willingly wronged[Pg 10] a person in his life, but was, on the contrary, ready to do a good turn for any one? Nancy had never forgiven Ned for having been given the place of school-master, to which she thought her own husband better entitled.

Ned's appointment was, in her eyes, a standing grievance, a shameful injustice, a cause for quarrelling, not only with him, but with all the world. "As if a fellow who has been accustomed to nothing but tarring old ropes, and running like a cat up the rigging, could be compared for one moment with a man like John Sands, who has been clerk for ten years in the parish, next to a parson, one might say, and who can draw out a certificate of baptism or marriage in the neatest and clearest of hands." Not that Nancy had herself much veneration for her husband, or, if report spoke truly, treated him with any kind of respect; but she did not choose that any one should be put over his head, least of all "that canting tar with a wooden arm," as she scornfully termed Ned Franks. Whenever Nancy met the school-master, she scowled at him under her black brows, as if he had done her a wrong. And she was never tired of speaking against him whenever she could get[Pg 11] a listener. Now she spoke of the arts with which he had wheedled himself into the favor of Mr. Curtis, the vicar, though every one knew that Ned was simple and straightforward as a child; then she spoke of his violent temper, pitied his wife, "poor unlucky soul!" from the bottom of her heart, though all in the village were aware that Persis Franks was one of the happiest wives in the world, and that if ever a young couple deserved the famous Dunmow flitch, she and Ned might have claimed it. The happiness of Persis was now as complete as earthly happiness can be; for after nearly three years of wedded life, the desire and prayer of her heart had been granted,—she had presented her first-born babe to his father. But this seemed a new grievance to Nancy Sands. Had not she, too, once had a son? and was he not lying under the shadow of the church-yard wall? Why should these Franks be so happy when she was childless? Why should all be sunshine with them when her sky was clouded with gloom? Nancy did not attempt to answer the question, but it soured her spirit; and the sound of the merry church-bells, chiming for the baptism of Franks's little son made her[Pg 12] feel as gloomy and wretched as when she had heard the knell tolled at the funeral of her own.

But we will not linger with Nancy Sands, but rather turn towards him who is at once the object of her outward scorn and her secret envy,—the one-armed school-master of Colme. A very gay scene meets our eyes on the green in front of the school-house, which is full of groups of village children seated on the grass, enjoying a simple feast of oranges, nuts, and home-made cakes; for, on the occasion of the christening of the first-born, Ned Franks entertains, in his homely fashion, all his scholars and their little sisters; he feels in his joy as if he should like to feast all the world. Every guest has a bunch of wild flowers,—the violets, cowslips, and primroses of spring; and merry is the sound of the prattle of nearly a hundred young voices, the ringing laugh, the snatches of song. Persis Franks, quiet and serene in her happiness, moves from group to group with her child in her arms, receiving the congratulations of all, and, with a mother's fond pride, drinking in the praises of her little treasure. Of course there was never such a beauty, at least in her eyes, as her little pink-faced babe, with his downy[Pg 13] head and dimpled fingers. Ned is less calm than his wife; being of a temperament naturally impetuous and warm, with rather more of the sailor than of the school-master in his manner, he shows the keen enjoyment of a boy. To the great amusement of his scholars, Ned displays his skill, maimed as he is, in dandling a baby three weeks old; and Persis, who, despite her confidence in her husband, feels a little nervous on account of her fragile treasure, is not sorry when the infant is once more resting upon her own gentle breast.

But the buoyant mirth of the young father is calmed down, and his sunburnt face, though still bright with happiness, wears a graver and more earnest expression when he stands up to address a few words to his guests. As he raises his right hand a little, all the murmur of merry voices is hushed at once, and for some seconds there is no sound heard but the soft breeze stirring the young leaves budding on the elms. Then Franks speaks a few earnest words; for, whether in sorrow or in joy, the teacher at Colme never forgets the office to which he has been appointed by his heavenly Master,—that of feeding, as far as he [Pg 14] has power to do so, the lambs committed to his charge.

"My children," thus the sailor began, "this is a very joyful, a very thankful, and also a very solemn day to me and my wife. We have seen, as it were, a little boat freighted with an immortal soul, launched on the wide sea, bound for the port of Heaven. If I did not trust that He who gave it will guide it, I should have many fears when I think of all the storms that it may meet on its course, the rocks and the shoals on which many a poor bark has been wrecked. But I have given my boy to God, and whether the voyage be a long or a short one, a rough or a smooth one, I trust that the little boat will drop anchor in the harbor of glory at last!" Ned paused a little, and Persis, as she bent down and pressed a long, fond kiss on her sleeping infant, left a tear on his soft cheek, but not a tear of sorrow; no feeling of misgiving dimmed the bright hope of the mother's heart.

"And now," continued Franks to his pupils, "let me just add a few words to yourselves. You also have all been launched on the great voyage, and I trust that you all have Faith for your compass, the Bible for your chart,[Pg 15] and heaven for your port; but I must remind you that you have need to keep a good lookout for breakers ahead, that you must steer warily, and mind your soundings. There's danger of running on the sandbank of the love of money, or of being drawn into the whirlpool of intemperance; there's the iceberg of falsehood on the one hand, the sunken rock of self-righteousness on the other. When temptation would, like a strong current, draw you near any dangerous place, don't trust your own seamanship, boys, to sail close under a rock and yet not strike it; give it as wide a berth as you can; sheer off, I would say, sheer off! And, above all, look straight up to Him whose wind alone can fill your sails, and bear you onwards in your course; look to him in storm and in calm, in gloom and in sunshine, praying that he may guide you here by his grace, and afterwards receive you to glory!"

The address of Ned Franks was simple and homely, characteristic of the speaker, and suited to the hearers, who were well accustomed to his sea-phrases. Franks had once compared himself to a buoy anchored down to warn vessels where navigation is dangerous;[Pg 16] and not only his pupils, but many a tempted one who came in his wandering course nigh to the school-master of Colme, had cause to thank God for the buoy. If the account of such a life of lowly usefulness as that of Ned Franks have any attraction for the reader; if, in his own voyage over life's perilous sea, while he blesses the beacon, he despises not the buoy; while honoring God's gifted ministers, if he feels that there is spiritual work also for those who have little eloquence but that of a consistent Christian life,—he may find in these pages something to interest him, and possibly, if God bless my humble labors, to help him to "sheer off" from some of the dangerous points where hopes have too often been wrecked, and promising barks have gone down.

"I'm afraid, Ned, that there were but poor collections in church to-day," observed Persis to her husband, as they sat together by the fire on the evening of the following Sunday.

"I'm not afraid, but I'm certain of it," replied Ned Franks. "Sands told me this afternoon that the whole collections after the two sermons only came up to four pound three, and when our poor vicar's bank-note was added, there were not ten pounds altogether. What are ten pounds to repair seven almshouses that have scarcely been touched for the last hundred years, and to build up another that has fallen down through sheer old age! The state of those cottages is a disgrace to the village. I wish that Queen Anne's old counsellor, when he built these eight almshouses for our poor, had left something for keeping the places in repair. Those still standing are hardly safe, and as for comfort—one would almost as lief live in an open boat as in one of them; they let in the wind from all the four quarters of the compass, and the rain too, for the matter of that."

"Poor old Mrs. Mills tells me that she is in fear every windy night of her chimney coming down through the roof, or of her casement being blown right in," observed Persis; "and Sarah Mason's wall leans over so to one side, that if it is not propped up soon, the whole cottage will be coming down with a[Pg 18] crash, and burying the old dame under its ruins!"

"I must see to that propping myself to-morrow after lessons are over," said the school-master, rather to himself than to his wife; "Ben Stone will give us a beam or two, like a good-natured fellow as he is; the worthy old woman shall not be buried alive if we can hinder it."

Propping Mrs. Mason's tumble-down wall would not be the first piece of work done by the one-armed school-master of Colme for the old almshouses in Wild Rose Hollow. Many a time had Ned clambered up to the top of one or other of the wretched dwellings, as actively as he would have made his way up into the shrouds of a vessel, to replace thatch blown away, or in winter to clear off the heavy masses of snow that threatened to crush in the roofs by their weight. Scarcely a day passed without some aged inmate of one of the almshouses hobbling to the school to ask Ned Franks if nothing could be done to mend a chimney that would smoke, or a window that would rattle, or whether there were no way of keeping the rain from making little ponds in the floor. Ned, with his one hand, was[Pg 19] more clever at "stopping a leak" or "splicing a brace" than most men with two hands, for he worked with a will; but when he had done all that he could for the counsellor's tumble-down almshouses, he was wont to say that no caulking of his could make such crazy old hulks seaworthy. "They need to be hauled into a dry dock, and rigged out new:" such was the one-armed sailor's oft expressed opinion, and it was one which no one could contradict.

"Everything seemed against our having a good collection to-day," remarked Persis; "our old baronet dead, and his lady away, dear Mrs. Lane absent in France, and, worst of all, our vicar still so ill, and unable to preach the sermon himself. His nephew the curate is very nice, but—but of course it is not the same thing."

"I'm afraid that half the people did not hear Mr. Leyton, and half of those who did would not understand him," observed Ned Franks; "yet he gave us true gospel sermons; there was nothing to find fault within the matter, and one shouldn't be too nice about the manner."

"Mr. Leyton is so young and shy," said[Pg 20] Persis, "he cannot speak with authority like his uncle, and then he scarcely knows any of us yet; but I dare say that when he gets courage—"

"I'll be bound you're talking of our young parson," exclaimed a jovial voice, as the door of the school-master's little room was thrown open, and Ben Stone, the stout carpenter, entered. Ben Stone always considered himself a privileged person, and usually omitted tapping for admittance. "I never care to knock," quoth the jovial carpenter, "unless I've a hammer in my hand, and a nail to drive in, and then there's a knocking and no mistake." Stone came in, nodded a good-evening to Persis, and taking possession of a chair by the fire, as if he felt perfectly at home, he stretched out his broad hands to the cheerful blaze, for the weather was rather cold.

"You were talking of the young parson," he continued; "he's not one to conjure money out of folks' pockets. Did you ever hear such a sermon? What had all the silver and gold, and shittim wood, and precious onyx-stones, that he talked of, to do with repairing a set of old almshouses? Our people might[Pg 21] open their eyes wide at his grand words, but they kept their purses close shut, I take it."

"The sermon had plenty of meaning; there had been much study spent upon it," observed Franks, who disliked criticism on preachers, and who had besides a kindly feeling towards the young Curate of Colme.

"Meaning! Oh, I dare say, if one could get at it," laughed the carpenter; "but when one wants to give a loaf of bread to a hungry man, one does not generally stick it at the top of a pole; there's not every one as can climb as you do, Ned Franks, or bring down onyx-stones and shittim wood to patch up rotten deal timbers. Why, there was but one little bit of gold to-day in the plate, and a scanty sprinkling of silver, though one might have thought the state of those wretched cottages would have preached loud enough of itself."

Persis and Ned could have told where that one little bit of gold had come from, and why it was that a certain hearth-rug with a pattern of lilies and roses which had taken the fancy of the school-master's wife, and was to have been a present from her husband on the anniversary of their wedding, still hung up in Grant's[Pg 22] shop, while their old one, faded and patched, still kept its place in front of their fire. But these family matters were things which the Franks never cared to talk of to others; they had given the gold with cheerful hearts, as a joint-offering to the Lord; and though it was more from them than a thousand pounds would have been from Sir Lacy Barton, they never thought that there was any merit in the little sacrifice which they had made.

"I dare say," continued Ben Stone, "that Mr. Claudius Leyton is a fine scholar, but he's no more fitted for parish work than a gimlet is to saw through a plank." While the carpenter was picking holes in the curate's preaching, he was at the same time, unconsciously of course, picking another with the end of his stick in Persis's unfortunate rug. "Why, he's afraid of the sound of his own voice, and can't so much as touch his hat to you, without blushing up to his eyes. It was rare fun to see him yesterday. He came to my workshop in the morning, to ask me where he could find Mrs. Sands, the wife of our clerk. 'Now,' thinks I, 'I know well enough why you want to visit Nancy. She showed in the face of half the village yesterday,[Pg 23] that she had had a drop too much, and you think that it's a parson's business to reprove as well as to teach. But if you ever screw up your courage to rebuke Nancy Sands, I'll give my new hatchet for a two-penny nail!' I told the young parson where Sands's cottage lay, just in sight of my own, and I watched him as he slowly walked towards it. I'd half a mind to go after him, and see how such a lamb of a shepherd would manage such a vixen of a sheep. I marked him shaking his head slightly as he walked, as if he were conning over what he should say; and though I could only see his back, I could just fancy the anxious, uneasy look on his smooth young face."

"Poor young clergyman!" said Persis. "He was about the most painful of all a minister's duties. I should be very sorry myself to have to rebuke Nancy Sands."

"Something like having to pull out a tigress's teeth!" laughed Ben Stone, who had succeeded in making a large hole out of a very little one in the old rug. "But Mr. Leyton never got so far as the pulling! I watched him, would you believe it, walk three times up and down before the gate of Nancy's little[Pg 24] garden; it was clear he couldn't screw up his courage to go in. Then she chanced to come out of her door. Maybe she was wondering why the parson took that bit of road for his quarter-deck walk, or she guessed what he was after, and thought she would brave out the business."

"Do you know what passed between the two?" inquired Franks.

"I saw Mr. Leyton raise his hat a bit, in his very polite way, and Nancy drop a little saucy bob of a courtesy, as who should say, 'What have you come here for?' and almost immediately afterwards the parson walked away a good deal quicker than he had walked to the place. I was curious to know what had passed, so I put down my saw, and went up the road to Nancy, who was still in her garden, pulling up groundsel; she has a rare crop of it there, and little besides. 'What said the young parson to you, Nancy?' says I. 'Oh!' says she, 'he hummed and hawed a bit, and then told me—as if I didn't know it afore—that as his uncle is ill he has come to this here place to do duty for him, and that I must remember;' and at that he stuck and stammered and blushed, so I took[Pg 25] him up sharp, and I says,—says I (Ben Stone mimicked the insolent toss of Nancy's head as he repeated her words), 'Yes, I remember this aint the first time as you've been at Colme; your mother brought you to the vicarage afore you was out of petticoats; that aint so very long ago.'"

"How could she?" exclaimed Persis Franks; but Ben went on with his story.

"'And so,' continued Nancy, 'he was put down in a moment and took himself off. I guessed what he'd come after, and I wasn't going to be lectured and preached to by a smooth-faced boy like that!'" Ben burst into a hoarse laugh, as if he thought the discomfiture of the youthful minister a very good jest; neither of his hearers joined in his mirth.

"Why, you don't seem to see the fun of it," cried Ben Stone; "but if you'd heard Nancy Sands, you'd have laughed as I do. The old tigress is more than a match for the shy young blushing boy of a parson."

Ben stopped suddenly short, for there was a knock at the outer door, and he was aware that whoever gave it must have overheard his last sentence, for Ben habitually spoke very[Pg 26] loudly. Moreover, there was something peculiar in the knock: it was unlike what would have been given by the knuckles of any rustic. The three in the school-master's parlor intuitively rose from their seats, even before the door was opened, and Mr. Claudius Leyton appeared.

The curate did indeed look extremely youthful. A small frame, delicate features, and a complexion like a maiden's, with smooth, fine, flaxen hair parted down the middle, gave the impression that the curate might be five or six years younger than he really was, and that a student's cap and gown would have suited him better than the dress which he wore. Notwithstanding his shy, nervous manner, however, Claudius Leyton was thoroughly the gentleman, and Ben Stone felt more awkward than he would have cared to own at his slighting observations having been overheard. The burly carpenter first made matters worse by a muttered "Beg pardon, didn't know who was there;" and suddenly becoming aware that an apology was a blunder, he said something about his old woman wanting him at home, and, in his hurry to make his escape, first dropped his [Pg 27] stick, then, in recovering it, stumbled over the cradle which was at the side of Mrs. Franks, and awoke the baby.

The cry of the infant effected a seasonable diversion; it covered the retreat of the carpenter, and gave Persis an opportunity of soon quitting the room and carrying the child upstairs, that the curate might have an undisturbed conversation with her husband. Franks placed a chair for Mr. Leyton with more of courteous respect than he would have shown to his cousin, Sir Lacy, the lord of the manor, while Ben Stone went home and made his wife merry with the account of what had occurred, wondering, between his explosive bursts of laughter, how the curate had liked to hear himself called "a blushing boy of a parson."

No one knows how often Claudius Leyton had repeated to himself, as if the words haunted him, the exhortation to Timothy, Let no man despise thy youth; nor what a burden the want of self-confidence, added to natural shyness, was to the Curate of Colme. Mr. Leyton lacked neither talent nor zeal, but he was painfully aware that as yet he had not the weight and influence with his flock[Pg 28] which every faithful pastor should have; and the young clergyman sometimes seriously contemplated wearing spectacles, although his sight was perfect, in order to take away that boyishness of appearance which marred his usefulness so much.

"I have many apologies to make, Mr. Franks, for calling so late, and on a Sunday evening," said Mr. Leyton, after nervously motioning to the school-master to take a seat opposite to him; "and I'm afraid that I've disturbed Mrs. Franks."

"You are welcome, sir, at any hour, and on any day," replied Ned, "for I am sure that you come on your Master's business. My noisy little man will be better upstairs."

"I'm anxious to consult you, Mr. Franks," said the curate, sitting forward in his chair, and speaking faintly, for his voice was weak, and two full services had almost exhausted his powers. "The proceeds of the collections[Pg 29] to-day are, as you are probably aware, insufficient—sadly insufficient for the purpose for which they are required. It is most unfortunate that the illness of my uncle prevented his preaching himself."

Franks could not speak a flattering untruth even to soothe the evident mortification of the poor young clergyman, who had spared no pains in preparing his unsuccessful appeals. There was a little pause, which was broken by Mr. Leyton.

"My aunt, Mrs. Curtis, wrote last week about the state of the almshouses to Mrs. Lane, and I sent a letter to Sir Lacy," (Mr. Leyton was related on the mother's side to the lord of the manor, as he was on the father's to the wife of the Vicar of Colme); "these are the only large proprietors in the parish. Neither my aunt nor I have as yet received any reply."

"You are never likely to get any from our new baronet," thought Franks, who knew well that the money of Sir Lacy was far more likely to go on the race-course, than in relieving the wants of the poor. He, however, only remarked aloud, "The silver and the gold is the Lord's, sir; and, as the need is[Pg 30] great, I trust and believe that he will send the supplies."

"The illness of Mr. Curtis prevents our being able to trouble him with anything like business," continued Mr. Leyton, "and my aunt scarcely quits his bedside. She and I have, however, been anxiously revolving what can be done; for if the almshouses be not soon put under thorough repair, not one of them will be standing next year, and their poor old inmates will have no home but the Union."

"That would fall especially hard on one like Sarah Mason," remarked Franks; "she has lived in her little cottage as wife and widow for twenty years, and her one earthly wish is to die in it. 'Twould well-nigh break her heart to be forced to turn out of the place."

"My aunt was suggesting to me that Bat Bell, the miller, is one to whom an appeal might be made. He has given nothing as yet to the cause."

"Nor is likely to give, I fear," said the sailor.

"He is rich, as I hear," observed Mr. Leyton.

"He has a thriving business at the mill, sir, and some hundred acres of land besides, which he lets to advantage. Bat Bell has but one child, for whom it is supposed that he is saving; for, if reports be true, Bat never spends one-half of what he gets, and must have put by enough of money to rebuild all the almshouses, if he choose to do so. But it is not always those who make most who are found most ready to part with their cash. If the heavily freighted vessel runs on the sandbank, the more she has in her the deeper she sinks; and if a man has passed half his life in getting, without giving, it needs a strong cable indeed, and a mighty power, to draw him off that sandbank,—the love of money."

"I have heard from my aunt something of the character of the close-fisted miller," said the curate; "yet, in our necessity, she thinks that a strong personal appeal ought to be made. The almshouses of Wild Rose Hollow can be seen from the mill; the object for which we plead is directly before the eyes of this Bell."

Franks smiled and shook his head: "Had mere pity been enough to draw him out, the money would have been forthcoming long ere[Pg 32] this, sir," said he. "Bat Bell has seen those cottages gradually falling to pieces year after year, and has talked with the old folks in them; yet I've good reason to know that not so much as a wisp of straw for thatching has ever come from the mill. Pity isn't a cable strong enough to move a nature like that of Bat Bell."

The young minister looked perplexed, and passed his hand across his forehead.

"But, sir," continued Franks, "we know that the shortest road to every man's heart is through Heaven, and it's not for us to give up any work for God as hopeless. No doubt the lady is right; there had better be a personal appeal."

A light flush suffused the countenance of the clergyman. He avoided looking at Franks, and played uneasily with the light cane which he held as he said, speaking with evident effort, "I came to consult you about it. I am a comparative stranger here; the parishioners scarcely yet know me, and—and it's a new thing to me to ask for money. I thought that if you were to speak instead of me, Mr. Franks, the appeal would have better chance of being successful."

Full before the mind of Claudius Leyton was his late encounter with Nancy Sands, and perhaps it was also remembered by the sailor, as he simply replied, "I can but try, sir."

An expression of relief passed over the face of the youthful clergyman. His thanks were brief; but when he almost instantly rose to take leave, he held out his hand to the school-master, and his fair small fingers closed on Ned's strong sunburnt hand with a kindly pressure, which told more than his words. When the door had closed behind Mr. Leyton, Ned Franks thought, with a smile, "That poor, shy young minister will sleep more soundly to-night from knowing that he is not to be the one to board Bat Bell. A gentleman like that feels it so awkward to play the beggar, even for the holiest cause."

On hearing the outer door close, Persis returned to her husband, and the babe, who had again fallen asleep, was gently replaced in his cradle.

"Persis," said the school-master, gayly, "I'm to go and try to draw money from the miller. I believe I might as well try to draw money from the millstone. I doubt whether Bell would put down half-a-crown to-day, to save[Pg 34] all the seven remaining almshouses from being pulled down to-morrow. But I could not refuse speaking to him, Mr. Leyton was so anxious about it."

"I wish you success," said Persis.

"Your wishes are stronger than your hopes, I take it. Bell is a thoroughly selfish man, except as regards love for his child,—sunk in the love of gold. It seems to me, wife, that we might almost divide the world into two classes,—those whose motto is 'Get, get,' and the other whose motto is 'Give, give;' those of the closed fist, and those of the open palm. The one set make money their idol; the other make money their servant. Now, we know that the love of money is the root of all evil; that is written in the Word of Truth; and if one sees the root in a man, what can one look for but evil fruits? Remember what our Lord himself said, How hardly shall they who trust in riches enter the kingdom of God!"

"But let us likewise remember what our Lord also said on the subject, dear Ned: With man it is impossible, but not with God, for with God all things are possible. Think of Zaccheus; he who had been covetous and[Pg 35] an extortioner,—the publican, who had clearly made money by false accusation, or he would never have spoken of restoring it fourfold."

"Ay, ay," replied Ned Franks, thoughtfully; "there was a vessel sunk over hulk—over bulwarks—deep in the sand, only the masts seen above it; and yet it could be drawn out, and cleansed, and righted, and floated, and sent on with a favoring breeze, as goodly and fair as if it had never grounded upon that dangerous bank. But it was the power of the Master that did this, and the love of Christ was the mighty chain that drew the publican from his old habits and evil ways, and made the covetous man give half of his goods to the poor."

"That power still can work—that love still can constrain," said Persis.

"So let us ask for a blessing on my visit," cried Franks. "I'll be up to-morrow before sunrise, to see to the propping of old Sarah's wall, and after the morning's lessons, I'll be off to the mill. Don't you wait dinner for me, Persis; maybe I'll not manage to get back till the boys meet for lessons again."

Ned Franks took down his cap from its peg, as soon as his merry young scholars, like a swarm of bees from the hive, had poured out from the low-browed porch of the school-house. But before he had time to start for the mill, Persis, baby in arms, was at his side, with a sandwich neatly put up in paper for her husband to eat on his way.

"No fear of my being put on half rations while wifie has charge of the stores," said Ned Franks.

He only lingered to kiss the soft little face of his babe, fragrant and sweet as a rosebud, and then set off for his visit to Bat Bell, though not very hopeful as to its result. The sun was shining brightly, the trees bursting into leaf; the lark in the blue sky, the thrush from its bough, were pouring forth songs of joy. Every sight, scent, and sound was a source of pleasure to Ned Franks.

"Those merry little fellows are piping aloft," thought he, "to cheer their mates in[Pg 37] their nests. Well may my heart sing, too, for who has such a home, and such a mate, and such a nestling as mine? The birds carol merrily, for they cannot look forward, the pleasure of the day is enough for them; but far more cause have I to sing, for I can look forward and think,—the spring-time is bright, but the harvest will be brighter; there is joy now, but the fulness of joy is to come! Ay, I can look forward and upward, too, and see what the birds cannot see,—the hand that scatters the blessings over my path, the Father's hand that filleth all things with plenteousness! And even like his free bounty should be that of his children; freely ye have received, freely give!"

A thin, weary wayfarer was sitting on the side of the path; his patched coat, his half-worn-out shoes, and sunken cheek told of need, although the man was no beggar. Following simply the impulse of his heart, Franks pulled out his sandwich and courteously offered it to the stranger. The smile and hearty blessing with which it was received sent the one-armed school-master on his way with a heart even more joyous than it had been a few minutes before. To give is a godlike pleasure, [Pg 38] and he who does not know what it is to do so with delight has missed one of the richest luxuries which man can enjoy below.

As Ned Franks passed along the high road, he could see in a neighboring field a man engaged in sowing.

"To bury seed is not to lose seed," thought Ned, "though it seem for a while to disappear, like money which is given to the Lord, or to the poor for his sake. A man who spends all that he has on himself or his family alone seems to me like one who grinds and bakes and eats all his seed-corn. He gains some present advantage, no doubt, but he will find want and dearth in the end, for he has not sown for the future. And the man who lays by and hoards what ought to be given in charity is like one who locks up his seed-corn in a chest until it grows mouldy and worthless. It neither feeds him nor grows for him; it is worse than good for nothing. While he that gives to the poor lends to the Lord, and the Lord will give him rich increase, not because of the man's deserts, but because of our heavenly Father's own free bounty towards those who seek to please him."

Ned, walking on with quick, active step, overtook Ben Stone, who, carrying his basket of carpenter's tools, was proceeding at a more leisurely pace in the same direction.

"Whither bound, messmate?" cried Franks, as he came up with the burly carpenter.

"I've a job at the Hall," replied Stone; "the new baronet will be coming down to the old house one of these days, and will want to find everything right there. Where are you going, Ned Franks?"

"I'm going to see if Bat Bell won't add something to the collection for the tumble-down cottages in Wild Rose Hollow. He was not at church yesterday."

Ben Stone burst out laughing, as he had a habit of doing upon the slightest occasion. "Going to ask Bat Bell for money! Going to try how much meal you can scrape off an old knife-board! ha! ha! ha! I put my shilling in the plate yesterday;"—the carpenter said this with a self-satisfied air, as one who felt conscious of having done the handsome thing;—"but I don't mind promising to double whatever you manage to squeeze out of Bat Bell; only, of course he mustn't know that I've said so."

"Don't make a rash engagement, messmate," said Ned Franks, with a smile; "I may come down upon you for some ready rhino."

"Well, and if you do," answered the good-humored carpenter, "I'll not flinch from my word. I've enough and to spare, and what one gives away, as we all know, goes to our good account in the end."

"That depends on the spirit in which we give," said Franks, more gravely, for he had good reason for suspecting that his companion held very mistaken views on the subject. "One can't keep a debtor and creditor account in heaven. We know from the Bible that a man might give all his goods to feed the poor, and yet that it might profit him nothing to do so."

"That's one of the texts as I never can make out the meaning of," said the carpenter. "To give is to give, and money is money; and why, when two men do exactly the same thing, one should have a blessing, and another none, quite passes my poor understanding."

"If one could suppose that all money given in charity could be put to a test, that only what is really offered for the Lord's sake should remain money, and all the rest be[Pg 41] turned into withered leaves, don't you think we should have heaps of dry leaves, as in autumn, to be scattered about by the wind? Consider all that's given for mere show, all that's given from natural pity, all that's given because it would be thought strange and mean to do less than others; none of that money is given to God, so we must not expect that God will accept it."

"Well, I grant ye this," said the carpenter, "if every man's almsgiving could be known only to himself and to God, there's many a one as gives now would keep his money snug in his pocket. But I'm not one of those, my good friend. I know, as we can carry nothing out of the world, that it's best to have something laid up in the bank above. But here your way divides from my way,—you go down the dell, I keep to the road. Good-day to you, Ned Franks, let me know what you get from Bat Bell; I'll be bound 'twill be nothing to ruin me. I've not much to do at the Hall to-day, but measuring and fitting, so maybe I'll be back before you return; just drop in at my shop and tell me what's your success;" and with a friendly nod and complacent smile, the carpenter went [Pg 42] along the high road, while the school-master turned down the little wooded lane which led to the mill.

"I should have liked to have had a little longer talk with Ben Stone," thought Franks. "I'm afraid that he thinks that he is actually buying God's favor, and earning heaven, by the little kind acts that he does! That's a kind of error which so many people run foul of. The sunken rock of self-righteousness is, maybe, just as dangerous as the sandbank of love of money. I must have a care that I don't take to judging others, and so split on it myself. I spoke very hardly yester-evening of Bat Bell the miller, yet, when I consider what a poor wretched sinner I am, receiving so much from God, and showing my gratitude in such a poor way, I'm scarce likely to run on that rock. When one measures one's little drop of charity, and even that not pure, with the great unfathomable ocean of love of Him who gave his life-blood for us, one is far more inclined to ask forgiveness for doing so little, than to expect reward for doing so much. There's nothing that can give the best of us any claim to the least of God's mercies, but the merits of Christ.[Pg 43] That is a truth that I see the more plainly the longer I live. To attempt to hold by one's own merits would be like trying to go to sea in a bark made of gossamer threads. The gossamer web looks goodly enough when the sunbeams are glinting upon it, and the dew-drops are nestling in it, but no man in his senses would trust his life to its power to bear up his weight. It would be a madder thing still for him to trust his soul's salvation to his own merits. If any mortal had anything in himself to boast of or to trust to, that mortal was St. Paul, who was ready to spend and to be spent; who had suffered the loss of all things for God,—a very different kind of self-denial from what we dare to call by that name,—and yet what was the feeling of St. Paul? Did he think thus he had earned heaven? Did he not say, God forbid that I should glory save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ? If we were to strip ourselves of all that we have, if we were to give away health and time and life itself for God's service, we should never get beyond that verse, we should have nothing whereof to boast, nothing (out of Christ) whereon to rest."

Ned had now descended to the bottom of a [Pg 44] beautiful little dell, through which gushed a rapid stream of water, turning the large wheel of Bell's mill. The wheel was, however, at this time still, and its monotonous clack did not mingle with the gurgle of the brook and the song of the birds. Franks had many delightful associations connected with that wooded dell; for there stood the cottage in which Persis, as a maiden, had dwelt with her aged grandfather; it was there that he had wooed and won her; from that little ivy-mantled nest he had, three years before, taken his bride to church. The cottage had now other inhabitants, but Franks could not pass the spot without stooping to pluck a violet to carry back to his wife.

"I'll give this to Persis," he said to himself; "she'll like a flower from the old home, though, thank God, I believe that she has never regretted leaving it for the new one. This much I can answer for, leastways, that every day since that happy one on which God gave her to me has made me prize his gift more dearly."

Bat Bell was a particular man, regular and precise in all his ways, who had, as it were, stiffened into his own mould, especially since the death of his wife, and who did not choose, as he often said, "to be put out for nobody." Bell hated a visitor at work-time, and he was so keen after making money that his work-time began early and ended late. He hated a visitor at meal-time, probably because he did not wish any one to share his meal. Franks was aware of this, and tried so to time his visit to the mill that he should catch Bell in that half-hour of rest which usually followed his early dinner.

"He'll be playing with his Bessy," thought Franks, "and there's nothing on earth that softens and opens a man's heart like hearing the voice of his own little child, or dancing it on his knee." Such was the conclusion to which the school-master came after his four weeks' experience of the feelings of a father.

Franks, however, found little Bessy, not [Pg 46] with her parent, but amusing herself in the lane close by the mill. She ran up to him with open arms, and held up her little face for a kiss, for Ned was a prime favorite with every child who knew him, and, during her mother's last illness, Bessy had spent a week at a time under the care of the Franks. She was a plump, rosy-cheeked, merry little girl, of about five years of age.

"Is father at home, my little lass?" asked Ned.

"Yes; father's in there," replied Bessy, nodding in the direction of the door of the cottage attached to the mill; "but he lets me be here to look for the flowers."

"Mind you don't go near the water, little one," said Franks; "keep to the primroses under the hedge;" and, smiling a good-by to the child, he proceeded to the dwelling of her father.

Bat Bell was alone in his parlor, seated on his high-backed wooden chair before the solid deal table, on which appeared the remains of some bread and cheese, and the empty pewter pot which had held his beer. Bell was a tall, bony man, naturally of rather a dark complexion, but skin, hair, and dress were all powdered with the flour which [Pg 47] showed what was his daily occupation, his shaggy black brows especially having formed a resting-place for the white dust, as the thatched eaves of a dwelling for snow.

"Good-day to you, Ned Franks, glad to see you; what brings you this way?" asked the miller, holding out his bony, whitened hand to his visitor, with as much of a smile on his face as the stiffness of the leathery skin would allow.

Franks was not one to approach any subject in a round about way; if there was any difficulty before him, he usually took what he called "a header" into the very middle of it. He did not say he had just looked in to see an old friend, or to ask if little Bessy would come and look at his baby, or utter any remark about the weather, or express any hope that business was brisk; he said what he had come to say the moment after he had taken a seat.

"I've called, neighbor, to talk to you about the almshouses yonder in Wild Rose Hollow;" through the window towards which Ned glanced as he spoke, the chimney of the nearest one could be seen. "I was up at [Pg 48] Sarah Mason's early this morning, to try what I could do for her wall; but no patching of mine can make the place fit for a human being to live in, let alone a rheumatic old woman. You know well the state of the cottages; something must be done for them without much delay, or the old hulks will soon fall to pieces."

Every symptom of a smile had disappeared from the hard face of Bat Bell as soon as his visitor had mentioned Wild Rose Hollow; and when Ned paused, the miller's only reply was a "humph," uttered in a very discouraging tone.

"Don't you think that it would be a shame and disgrace to Colme, if dwellings that have afforded shelter for two hundred and fifty years to the aged respectable poor of our village were all suffered to go to utter decay from neglect, as one of them already has done?"

"Why don't young Sir Lacy mend 'em? He has money enough," said the miller, "and flings it away right and left, they say, in ways that are little to his credit."

"If he does not come forward, is his backwardness an example to be [Pg 49] followed?" asked Franks.

"Let the clergy see to it; it's their business," said Bell, with a little disagreeable twitch of the nostril, which with him was always a sign that something was "putting him out."

"Mr. Leyton preached twice yesterday in aid of the work, but the collections made were wretched,—not one tenth of what is absolutely required."

"The parish overseers must do something."

"They refuse to stir a finger," said Franks; "they say it's no business of theirs."

"Then I'm sure that it's no business of mine," interrupted the miller.

"Is it no business of ours," said the school-master, earnestly, "that they whom we have known for years, they who have lived amongst us, and hoped to die amongst us, should be deprived of the comfort, the quiet, the independence which they so dearly prize?"

"I'm sorry for them," said the miller, carelessly; "the founder should have left something to keep the wheel going."

"What is wanted is the full stream of Christian love," observed Franks. "There are scores of charities in London kept constantly working by [Pg 50] nothing but that stream."

The miller did not look as if he had a drop of such love within him. "It is clear," thought Franks, "that I'm not in the right tack yet. Let me try him on that of conscience. Why," he continued, aloud, "there's no plainer command in the Bible than To do good and to distribute, forget not; let us do good unto all men, and specially unto them that are of the household of faith."

"I know something of the Bible, too," replied Bat Bell, coldly, and the twitch was more unpleasant than before. "I'm a father, and I don't forget that it's written that He who provideth not for his own is worse than an infidel."

"Never let that text be repeated to justify hoarding!" exclaimed Franks, with some warmth, for it flashed across his mind how the devil himself can quote Scripture. "If we are to be content with food and raiment for ourselves, shall we not be content with them also for our children, without gathering up for them gold and silver, which may only prove a snare, as has happened in thousands of cases? I am a father, too," Ned added more mildly, for he saw on the countenance of Bell [Pg 51] that he had spoken too warmly; "I am a father, and love my little one as much as a father can love; but if thoughts of saving for him made me close my hand and heart against the claims of God's poor, I should feel, that whatever else I might leave him, I dared not expect to leave him that blessing which alone giveth true riches. I should feel that my babe was coming between my soul and my God, and that I must look for God to punish me in him. Of whatever we make our idol, the Lord is wont to make his rod."

"I've no such superstitious fears!" cried Bat Bell, rising from his seat with a gesture of impatience. Had his visitor been any one but Ned Franks, from whom he had received kindness in time of sorrow, he would have given his guest a broader hint to depart.

"Let us not talk of fear, then, neighbor," said Franks, also rising, but with no intention of yet giving up his attempt to move that cold, hard heart. "Have patience with me a few moments more, while I speak of a nobler motive,—the love of God. Look around you, Bat Bell, look at this comfortable home, where want is unknown; you were ill last [Pg 52] winter; look at the health and strength restored you now; listen to the merry voice of your child,"—a joyous carol was heard from without,—"and then ask yourself from whom came all these blessings, the loss of any one of which would throw you into sore distress. The goods that you have you owe"—

"To hard work, the labor of my hands in the sweat of my brow," interrupted the miller.

"Who gave the hand strength and the mind reason? whose power made the stream which turns your mill? whose sunshine ripens the corn on your fields? But why speak only of earthly blessings,—we have more, far more to thank God for! We have not only bodies but souls to care for; we have not only time but eternity to live for. Can we be content to sit still and do nothing for others, when we know what God's Son hath done for us; when we think at what a price he bought our salvation; how, though he was rich, yet for our sakes he became poor? He calls us to make no sacrifice for him that he has not first made a thousand-fold for us; and when he would teach us what charity should be, the [Pg 53] Lord sums up all in the words, Love one another as I have loved you."

Ned Franks's appeal was interrupted by the door being thrown suddenly open, and little Bessy's running into the room. The white pinafore of the child, held up by one chubby hand, formed a receptacle for a number of wild flowers which she had been gathering in the lane. With her blue eyes sparkling with pleasure, the child ran up to her father.

"See, I've plucked 'em for you, every one!" she cried, emptying her pinafore on the chair from which Bat Bell had lately risen; "no,—all but this dead primrose,—it's withered and bad, it's not fit to give father!" Bessy threw the faded flower away. "I've brought you the first I could find; now, I'll run and get more for myself."

Bell caught up his girl, lifted her up high, and then kissed her again and again before he set her again on the floor. Bessy nodded merrily at Ned.

"You shall have some, too," she said; "but the first are always for father;" and away ran the happy child, leaving her spring flowers behind her.

And Bessy left something besides. The visit of the little one had [Pg 54] seemed to bring sunshine with it. The hard lines on the parent's face were softened, every feature relaxed, the cold, money-making man was a parent, and a fond parent still. Franks felt that the unconscious Bessy had acted the part of a little ally; that she was helping to stir the deeply-imbedded vessel which he had been trying to move.

"Will that dear little girl enjoy her flowers less because the first are always for her father?" said Franks, as soon as the sound of the pattering feet was heard no longer. "Would that God's children were more like her, bringing their gifts with readiness, with joy, and not like too many of us, offering only the withered thing, the dead thing, that which we will not miss, to him whose goodness towards us has been greater than that of any father on earth!"

Bat Bell's hand approached his pocket, though he did not actually put it in. "Ned Franks," said the miller, "I tell you honestly, that I wouldn't stand this kind of talk from any man but yourself; but I know that your practice is better than your preaching; so, as you've set your heart on getting something for these cottages, just as a matter [Pg 55] of favor to you"—Bell stopped short; he could not make up his mind either to finish his sentence, or to draw out his purse.

"I do not want you to give as a matter of favor to me," cried Franks, "nor is the state of the cottages what is uppermost now in my mind. I came here, indeed, anxious to get something for them, but I am a hundred-fold more anxious to get something for you!" The miller raised his dusty eyebrows with surprise, but Franks went on, without giving him time to interrupt the earnest flow of his speech. "If we knew that our Lord and Master had come down again to this earth, that he was in our land, our country, our village, nay, that he was deigning to dwell in one of these cottages, which, wretched as they are, are better than the Bethlehem stable, would we not deem it the first of honors to be allowed to bring gifts to him? Would not you and I be ready to pull down our own dwellings to get beams and rafters for his, and think the best that we have, yea, all that we have, too little to offer to our King? And it is all the same, Bat Bell: what we give to the poor for his sake, Christ receives as given to himself. Inasmuch as ye did [Pg 56] it unto the least of these, my brethren, ye did it unto me. Yes, my friend, I want help for the cottages, but I much more want something for you,—the joy of hearing at the last day the Saviour's welcome, Come, ye blessed of my Father."

The fervent appeal, coming as it did from the very heart of the pleader, had stirred the stubborn hearer a little, though but a little way from his first position. Bat Bell could not help remembering that there was a reverse to the blessing, a "Depart ye cursed," for those of whom Christ would witness, "Ye did it not unto me." Bell feared that he might have lived all his life under the shadow of that curse; so, anxious to justify himself to his own conscience even more than to Franks, he took refuge in the remembrance of what he deemed a good deed.

"I can give,—I have given, and largely,[Pg 57] too," said the miller, leaning his head against the wall. "There's my nephew, Rob Gates; did I not pay fifty pounds to 'prentice him out,—fifty pounds," repeated the miller emphatically, "of which I have not had one penny back, though the ungrateful dog has been in business these three years?"

Upon this one act of generosity Bell always fell back when any call on his charity was made, as if he considered that the lent fifty pounds covered every claim which could be made on his purse by religion or by humanity. It always gave him an opportunity of declaiming against the ingratitude of mankind; because his nephew had not repaid his loan, all who needed aid from the miller became in his eyes covetous and thankless, if not dishonest. Bat Bell tried to believe that in hazarding fifty pounds he had already given enough to God; it would have startled him to have been told that not one farthing of the money could be reckoned as real charity. Bell had helped his nephew from natural affection, and from family pride. The miller had acted exactly as he would have acted if he had been a Turk or an Infidel,—exactly as he would have acted had he never heard the name of the[Pg 58] Lord. Tried by this test, of how small a part of our alms, alas! will the Master be able to say, Ye did it unto me!

"That miserable fifty pounds," thought Ned, who had heard of it often before, and who knew too well that the miller used its loss as a perpetual argument to silence conscience, and excuse his neglect of the poor.

"You see, Ned Franks," continued the miller, "a man who has once made sacrifices for others, and has only met with ingratitude; who has spent upon a good-for-nothing scapegrace of a nephew—"

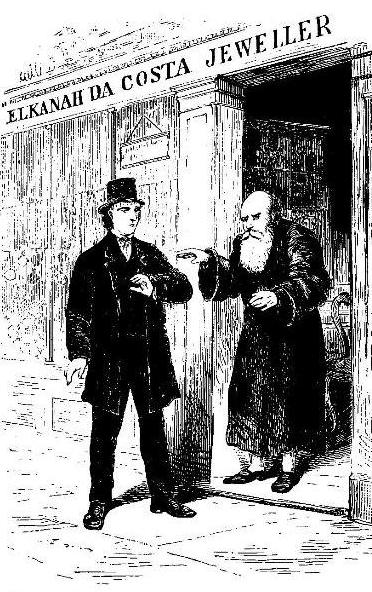

The miller suddenly stopped and started. Ned, whose back was towards the open door, only knew by the change on the face of Bell, the look of surprise that flashed across it, that a third party had unexpectedly joined them. Turning round he saw a stout young man, in a shaggy coat, with a knapsack on his shoulders, and a broad grin on his good-humored face, who advanced with both hands extended to the miller, exclaiming in a loud, hearty tone, "Here's the good-for-nothing scapegrace to answer for himself."

"Here's the good-for-nothing scapegrace to answer for himself." p. 58.

Bell gave his nephew a cordial welcome both with hand and voice, and Franks was so[Pg 59] glad to see the hearty greeting, that he did not ask himself whether it were possible that the uncle's pleasure at seeing the young man might partly be owing to the hope of his now having the old debt cleared off.

"So you were giving me a pretty character, uncle," cried Rob Gates, after he had thrown himself on a chair; "well, I can't grumble at that, as you've neither seen nor heard from me for many a long year; but I never was much of a scribe, and don't trouble the postman from January to December. I don't care to write till I've something to say, so I waited till I could play the postman myself, and bring a kind of notes that are easily read, and will tell more of gratitude, duty, and that sort of thing, than reams of foolscap scribbled all over."

With a look of honest satisfaction, the young man pulled a large leathern pocket-book from his breast-pocket. His movements were watched with keen interest by the miller, as Rob opened the clasp, and then slowly drew out, one after another, unfolding and smoothing out each as he did so, ten five-pound notes of the Bank of England. He spread them with his broad, rough hands[Pg 60] over the table, as if he took a boyish pleasure in making the greatest possible show of his wealth.

"Uncle, here's the fifty pounds which I owe you," said Rob; "you're not sorry now, I hope, that you lent a helping hand to your scapegrace of a nephew? I can't believe that a fellow ever has cause to be sorry for doing a kindness; it always in one way or other comes back."

Franks glanced at the miller, and fancied that he saw his thin lip quiver a little, and that something like moisture rose in the usually dark, cold eye. Ned could not tell what was passing in the mind of that man, as he laid his hand on one of the notes. Slowly, half reluctantly, the miller raised it, and then, as if moved by an impulse, which even his selfish nature could not withstand, Bell handed that note to the sailor, saying, "You came at a lucky time; take that,—it's for Wild Rose Hollow."

Ned stood amazed at success so far beyond all his hopes. He had indeed been led to that dwelling in a happy moment, when Bell's hard heart had been softened and touched, or, to use his own simile, "when a spring-tide[Pg 61] had set in so strongly as to help the stranded craft off the shoal." His words of thanks were hearty, and while the miller set about preparing a meal for his hungry guest, the one-armed sailor joyously started on his homeward way.

Merrily Franks sped up the glen, his blithe whistle mingling with the chord of the lark that hung quivering over his head. Ben Stone, the carpenter, who had just returned from the hall, was standing at the door of his shop, on the lookout for Ned Franks.

"Why, he looks as gladsome as if he'd just come in for a fortune himself," muttered the carpenter, "and he's whistling away like a bird! But all that jollity must be put on to cover disappointment, for if he got more than a crooked four-penny bit from that miserly miller, I'm a Dutchman, that's all! Well, Ned Franks," cried the jovial carpenter aloud, "how many brass farthings has Bat Bell pulled out of his hoard to prop up the houses in Wild Rose Hollow?"

Franks waved the crisp, fluttering bank-note in reply.

"You don't mean—what—no—not a bank-note—a five-pound note!" exclaimed[Pg 62] the astonished Stone, scarcely able to credit his eyes. His exclamation was echoed by his wife and two neighbors who joined him at the moment.

"It must be a toy-note," suggested Mrs. Stone.

"No," laughed Ned, "it is a good honest note of the Bank of England, worth five sovereigns of any man's money. Bat Bell was unexpectedly repaid a large loan at the very time when I was with him to ask help for Wild Rose Hollow; the first note which he touched he gave to God, and I trust that God will bless him for it," added Franks, with fervor; "it was more from him than a much larger sum would have been from another man."

"The sum's pretty large from anybody," said the carpenter, with rather a rueful face, for Bat Bell's generosity had taken him by surprise in an inconvenient way. "I hope that I'm not expected to hold to my unlucky offer; where Bell gives once, I give a hundred times; he may plump out a five-pound note and not miss it, but I've not the knack of turning deal shavings into gold."

"No, no, neighbor," cried Franks, "no one would think of holding you to such a bargain.[Pg 63] You have not suddenly come into money like Bell, or, I've not a doubt, you'd give to the full as large as he."

"But I'm not the man to flinch from my word," said Stone; "if I can't give the money, I'll give the money's worth in work when I've time to spare; so you may count that five pounds as fairly doubled, my friend."

"That will be a lucky bank-note to you, Mr. Franks," observed the carpenter's wife; "for now that you've brought in such a sum to help the collection, I'm sure and certain that you'll be the man fixed upon to be clerk at our church, instead of John Sands."

"Instead of Sands! why, he's not going to resign the place, surely?" cried Franks.

"He'll have to give it up; he could not for shame stand up just below the reading-desk, give out the psalms, and lead the singing, as if nothing had happened," observed Ben Stone, with a shake of his head.

"Why, Sands is the most quiet, steady, sober—"

"But his wife, she's the mischief, she's the ruin of him; a man is what a woman makes him," quoth the jovial carpenter, giving a [Pg 64] self-complacent nod towards his own partner. "Parsons, we're told, must have their own houses in subjection, and I guess the same rule holds with their clerks. All Colme is talking about it. We'll have you, our one-armed sailor, clerk as well as school-master; there's no one so fit for the place!"

"So there's a chance of my being made clerk as well as school-master of Colme," said Ned Franks to himself, as he walked towards his home. "Such a breeze of good fortune is more than I ever could have hoped for. Why, there would be twenty-six pounds a year, besides what I have now, and no trifle in the way of fees! Now that I am a family man, I shall find plenty to do with the money. I shall be able to fulfil my heart's desire, to give my boy, when he's old enough to learn, a first-rate education. Little Ned shall have every advantage, bless him! There's no saying what he may turn out in time,—may [Pg 65] be a parson, maybe a bishop, one of these days!" Franks laughed to himself, and walked on with brisker step at the thought. "Then I'll be able to insure my life, so that if anything should happen to me, my Persis shouldn't be cast adrift on the waves, or have to pull the oar herself in a heavy sea! And we'll have something to give to others. I think that I'll devote the fees for the first year, at least, to the repair of the old almshouses in Wild Rose Hollow. Persis will approve of that, I am sure. Grand news I have to carry home to wifie to-day! When I was nothing but a poor Jack-tar, and then lost my arm by an awkward accident, and thought that the storm of misfortune was throwing me back on my native shore like a battered wreck that never would float again, how little I dreamed what a prosperous gale that storm was for me! Here am I, as far from being a wreck as ever I was in my life (barring that instead of my left arm I've timber and a hook, which serve my purpose quite well), scudding along, buoyant as a cork, with the best of wives and the sweetest of babes and the happiest of homes, with teaching work, which is just to my liking, and now[Pg 66] with the prospect in addition of being appointed Clerk of Colme, in the place of John Sands!"

But the last words, like a touch to a sleeper, broke the charm of Ned Franks's pleasant day-dream.

"Shame on me!" he muttered, half aloud; "here am I rejoicing, like a shameless wrecker, in the ruin of a poor fellow who never did harm to me or mine! The proverb says, 'It's ill standing in dead men's shoes,' but this is something worse. If poor Sands has to resign the snug berth he's held with credit for the last ten years, it will be because he has the misery of having a wife who has taken to drink; her disgrace falls upon him, and because his home is wretched, he may have the very bread taken out of his mouth! Instead of feeling for him, as any man, let alone a Christian, should feel, I, who have had my cup of blessings already filled to overflowing, I am counting on his loss as my gain; because his happiness is shipwrecked, I'm looking to get my share of the spoils! Out upon me for a selfish, covetous fellow!" exclaimed the indignant tar. "That same prosperous gale that I thought so much of seems[Pg 67] to be blowing me right on that sandbank of love of money, from which I've been warning others. I must take care to sheer off myself!"

The road along which the school-master of Colme was passing, led him by the cottage of Sands the clerk, and he glanced, as he went by, at the untidy, weed-grown garden, the window with the broken pane stuffed with rags, which told a sad tale of sorrow and neglect. The cottage was rather a large and good one, and a few years back had worn an appearance of comfort and prosperity, such as befitted the home of the respectable Clerk of Colme. Franks remembered the lines stretched out along the garden, whitened with linen hung out to dry; for Nancy Sands, a strong and active woman, had added many a pound to her husband's gains by her skill in laundry-work. Now one of the poles lay rotting on the ground; a broken, dirty cord, hanging loose from the wall, was all that remained of the lines. Families no longer cared to trust Nancy Sands with their washing, and, if report spoke truth, the poor clerk had sometimes to iron his own shirts himself,[Pg 68] to keep up the decent appearance indispensable to one in his station.

Ned Franks had not gone many yards past the dwelling of Sands, when he saw before him the poor man himself, advancing slowly, as if there were little to attract him towards his home. The figure of the Clerk of Colme, by its peculiar stiffness and formality, was easily recognized at a distance. He always dressed in black, and so appropriate did the cloth appear to the wearer, that no one could imagine John Sands appearing in any less grave attire. Even in his best days the Clerk of Colme had seemed as if he could never look happy. The closely cropped hair, black and almost as thick as the fur of a beaver, was seen above a thin, sallow face, always so solemn and serious that it was supposed to be incapable of smiling. There had been some thought, years before the beginning of this story, of appointing John Sands as school-master at Colme; but there was not one of the scholars who would not have regarded such an appointment with exceeding dislike and disgust. The boys were certain that the old raven, as they called the clerk, must have been brought up in an undertaker's shop, and[Pg 69] been cradled in a coffin; they believed that he had never laughed when a baby, nor played at cricket or football when a boy; indeed, a doubt was expressed as to whether the clerk had ever been a boy at all, but had not rather grown out of a Liliputian man, clad in a tiny black coat, and miniature white neck-cloth. No one was very intimate with John Sands; no one ever addressed him by his Christian name, or thought of clapping him on the shoulder, or telling him a bit of good news, or asking him to "come and share pot-luck." Yet nothing could be said against the clerk, except that he did not rule his own house well, and was thought to be henpecked by Nancy.

When the sailor (for such Franks still considered himself, and was considered by other to be, though he had not been afloat for years) saw John Sands coming towards him, he had something of a feeling of shame; it seemed to his kindly, honest nature as if he had done his neighbor wrong by even thinking of taking his place. Franks lifted his cap with a courteous "Good-day," as he was about to pass John Sands, but the clerk stood[Pg 70] stock-still on the path, and clearly did not wish to be passed.

"Mr. Franks," he said, to the sailor, "if you could spare me a few minutes, I should like to have a quiet talk with you. The church is hard by; will you come with me into the vestry?"

Now Franks was in great haste to get home; he was impatient to tell his wife of his wondrous success with Bat Bell; besides, having given away his breakfast, he was exceedingly hungry; for, having risen at four o'clock that morning, and having eaten nothing since an early breakfast, his sharp appetite reminded him that it was long past his usual dinner-time. Franks had calculated on having just a quarter of an hour in which to satisfy hunger, and tell all his news, before his pupils would gather again for afternoon lessons. Had John Sands not been in trouble, Franks might have asked him to put off his proposed quiet talk; but the sailor was sorry for Nancy's husband, and only reminded the clerk that lessons would begin again at two, and that the school-master must be at his post.

Franks doubted whether Sands had even[Pg 71] noticed this hint. The clerk turned back, and, at a slower pace than was pleasant to his hungry companion, proceeded towards the village church, not uttering a single word as he went. The two passed along the little walk which led to the back door which opened into the vestry. The clerk very slowly, at least so it seemed to Franks, drew the large key out of his pocket, and fitted it into the lock. The creaking door was opened, and the two men entered the little room which looked so neat, solemn, and silent, with the light from the diamond-paned window falling on its green cloth-covered table, with the heavy desk, and the big registry book upon it. It is probable that the clerk felt more at home in this place than in his own cheerless dwelling; here at least there was peace.

There were in the mind of Ned Franks very pleasant recollections connected with that vestry-room. The very chair which he now took had been occupied by his bride, when, for the last time, she had signed herself "Persis Meade;" in that place he had first called her "wife," and there, but two days ago, their first-born babe had been registered [Pg 72] as received by baptism into the church. The clerk also seemed to have the latter event in his mind; for, as he seated himself under the window, with his back to the light, he observed, in the slow, measured tone which he always used, "Your child was christened in this church on last Saturday, Mr. Franks."

"If that is all he has to say to me," thought the half-famished sailor, "I need scarcely have lost my dinner for it;" but he waited, with what patience he could command, for the next slow sentence which might drop from the lips of John Sands.

These two men, who had once been rival aspirants for the post of school-master at Colme, formed a singular contrast to each other,—Sands, with that primly-cut hair, which lay like a judge's black cap on his head, and his face as grave as if he were that judge pronouncing sentence; Franks, with light brown locks, which seemed to curl themselves round with very good-humor, and bright blue eyes, always ready to sparkle with fun, as well as to beam with kindness. No one could wonder at the preference felt by the boys for the one-armed sailor, though[Pg 73] he had not half the learning of Sands. We know that he that hath a merry heart hath a continual feast; and where such a heart is possessed by a school-master, his boys enjoy, as it were, the crumbs of that feast. Ned Franks's inspiriting "Now, my hearties, let's to work," would set his scholars to their tasks with a cheerful energy almost as great as that with which they rushed out to play. The sailor felt that these young beings were entrusted to his care, not merely that he might teach them to be wise, but help them to be happy; and the influence which he thus gained over their affections greatly aided Franks in reaching the very highest mark of education,—that of training young immortals to be wise unto salvation, and happy because serving the Lord.

"Mr. Franks, you have a happy home," said the clerk, after a little pause; and then he added, with a sigh, "so had I once."

Ned knew not what to reply; he thought that all England held no two women more unlike each other than Nancy Sands and his own sweet Persis.

"You see, Mr. Franks," continued the clerk, drooping his head, and looking on the carpet, "it was all sorrow that did it. There was not a better manager in Colme than Mrs. Sands, till—till we buried our only boy;" the poor man's voice faltered as he spoke; "and then she fancied that there was comfort in a drop. I don't mean to say she was right, but it's too common a mistake; I—I think the world's hard upon her, Mr. Franks,—she has been tempted, grievously tempted; but there's very good metal in her yet."

There was something touching to the sailor in the effort of the poor injured husband to throw a veil of indulgence over the glaring fault of his wife. Though her intemperance was ruining his comfort, and disgracing his name, and might seriously injure his worldly position, Sands's anxiety was to find some excuse for his wretched partner. For the affections of the quiet, stiff, formal man still clung to the choice of his youth.

John Sands had loved Nancy almost from[Pg 75] his boyhood; often had he been jested about his fancy for the boisterous black-eyed girl, who cared so little for him. When Nancy had grown into a bold, self-willed woman, ready enough to receive his attentions, but trifling with his feelings, and not returning his love, Sands had seen, time after time, some rival preferred to himself, and had heard, with silent anguish, that the only girl that he had ever cared for was to be married to some one else. Yet, somehow or other, every engagement of Nancy's was broken off; perhaps few men, when it came to the point of decision, would have wished to be linked for life to Bangham's termagant daughter. So, after many long years of patient, sorrowful waiting, John at length had the wish of his heart granted, and found, as too many find, that he had chosen ill for his own peace of mind. Nancy might have made a good, hard-working wife to a man who would have ruled as well as loved her,—one who would have taught her to obey; but where she should have had a master, she found a servant; she despised Sands for his very anxiety to please her, and readiness to yield to her wishes. There was no open rupture between them;[Pg 76] the wife ruled and the husband obeyed and never complained, till at length Nancy's indulgence in the vice of intemperance made John's misery a thing which no longer could be concealed from the world.

The clerk seemed to expect some reply. The sailor was puzzled what to say; he feared to hurt Sands by expressing any pity, and he was too sincere to express any hope. But as the dead silence became very painful, Ned broke it by saying, "I wish with all my heart I could help you."