THE HISTORY

OF THE

FIRST WEST INDIA REGIMENT

BY

A.B. ELLIS

Major, First West India Regiment

AUTHOR OF "WEST AFRICAN ISLANDS" AND "THE LAND OF FETISH"

London:

CHAPMAN AND HALL, Limited

HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN

1885

CHARLES DICKENS AND EVANS

CRYSTAL PALACE PRESS

I beg to return my best thanks to A.E. Havelock, Esq., C.M.G. Administrator-in-Chief of the West African Settlements; Lieutenant-Colonel F.B.P. White, of the 1st West India Regiment; V.S. Gouldsbury, Esq., Administrator of the Gambia Settlements; A. Young, Esq., Lieutenant-Governor of Demerara; F. Evans, Esq., C.M.G., Assistant Colonial Secretary of the Gold Coast Colony; Alfred Kingston, Esq., of the Record Office; and Richard Garnett, Esq., of the British Museum, for the very valuable assistance which they have rendered me in the collection of materials for this Work.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER | 1 |

CHAPTER I. | |

| THE ACTION AT BRIAR CREEK, 1779—THE ACTION AT STONO FERRY, 1779 | 26 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| THE SIEGE OF SAVANNAH, 1779—THE SIEGE OF CHARLESTOWN, 1780—THE BATTLE OF HOBKERK'S HILL, 1781 | 33 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| THE RELIEF OF NINETY-SIX, 1781—THE BATTLE OF EUTAW SPRINGS, 1781—REMOVAL TO THE WEST INDIES | 43 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE EXPEDITION TO MARTINIQUE, 1793—THE CAPTURE OF MARTINIQUE, ST. LUCIA, AND GUADALOUPE, 1794—THE DEFENCE OF FORT MATILDA, 1794 | 53 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| MALCOLM'S ROYAL RANGERS—THE EVACUATION OF ST. LUCIA, 1795 | 63 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE CARIB WAR IN ST. VINCENT, 1795 | 69 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| MAJOR-GENERAL WHYTE'S REGIMENT OF FOOT, 1795 | 77 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE CAPTURE OF ST. LUCIA, 1796 | 85 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE RELIEF OF GRENADA, 1796—THE REPULSE AT PORTO RICO, 1797 | 93 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| THE DEFENCE OF DOMINICA, 1805 | 103 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE HURRICANE AT DOMINICA, 1806—THE REDUCTION OF ST. THOMAS AND ST. CROIX, 1807—THE RELIEF OF MARIE-GALANTE, 1808 | 117 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE CAPTURE OF MARTINIQUE, 1809—THE CAPTURE OF GUADALOUPE, 1810 | 125 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| THE EXPEDITION TO NEW ORLEANS, 1814-15 | 141 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE OCCUPATION OF GUADALOUPE, 1815—THE BARBADOS INSURRECTION, 1816—THE HURRICANE OF 1817 | 160 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE DEMERARA REBELLION, 1823 | 170 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| THE BARRA WAR, 1831—THE HURRICANE OF 1831—THE COBOLO EXPEDITION, 1832 | 178 |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

| THE MUTINY OF THE RECRUITS AT TRINIDAD, 1837 | 188 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE PIRARA EXPEDITION, 1842—CHANGES IN THE WEST AFRICAN GARRISONS—THE APPOLLONIA EXPEDITION, 1848 | 208 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

| INDIAN DISTURBANCES IN HONDURAS, 1848-49—THE ESCORT TO COOMASSIE, 1848—THE SHERBRO EXPEDITION, 1849—THE ESCORT TO RIO NUNEZ, 1850 | 218 |

CHAPTER XX. | |

| THE STORMING OF SABBAJEE, 1853—THE RELIEF OF CHRISTIANSBORG, 1854 | 228 |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE TWO EXPEDITIONS TO MALAGEAH, 1854-55 | 236 |

CHAPTER XXII. | |

| THE BATTLE OF BAKKOW, AND STORMING OF SABBAJEE, 1855 | 248 |

CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| CHANGES IN THE WEST AFRICAN GARRISONS, 1856-57—THE GREAT SCARCIES RIVER EXPEDITION, 1859—FIRE AT NASSAU, 1859 | 257 |

CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| THE BADDIBOO WAR, 1860-61 | 265 |

CHAPTER XXV. | |

| THE ASHANTI EXPEDITION, 1863-64 | 276 |

CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| THE JAMAICA REBELLION, 1865 | 286 |

CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| AFRICAN TOUR, 1866-70 | 298 |

CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| THE DEFENCE OF ORANGE WALK, 1872 | 304 |

CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| THE ASHANTI WAR, 1873-74 | 317 |

CHAPTER XXX. | |

| AFFAIRS IN HONDURAS, 1874—THE SHERBRO EXPEDITION, 1875—THE ASHANTI EXPEDITION, 1881 | 333 |

APPENDIX | 343 |

INDEX | 361 |

MAPS.

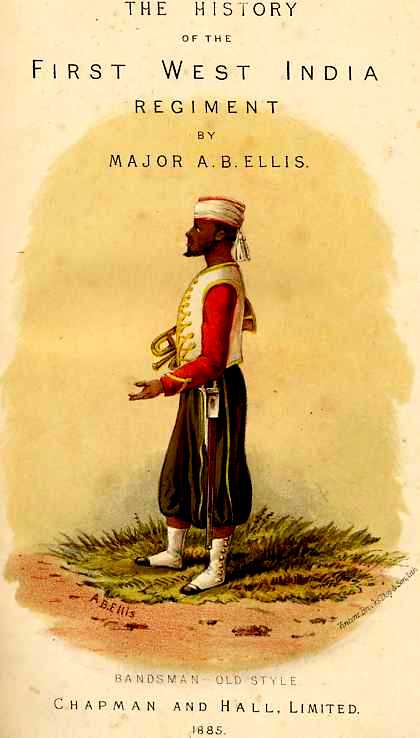

| 1. ST. VINCENT | facing page 69 |

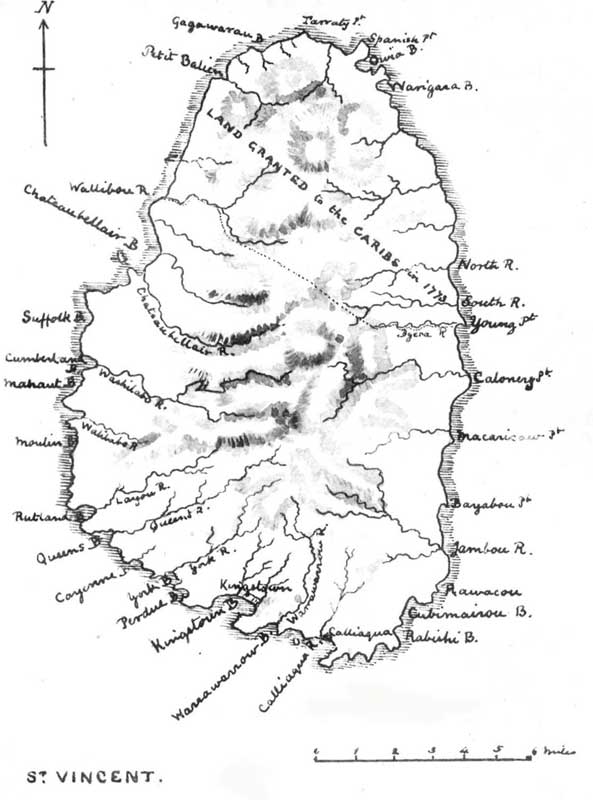

| 2. GRENADA | 93 |

| 3. DOMINICA | 103 |

| 4. MARTINIQUE | 125 |

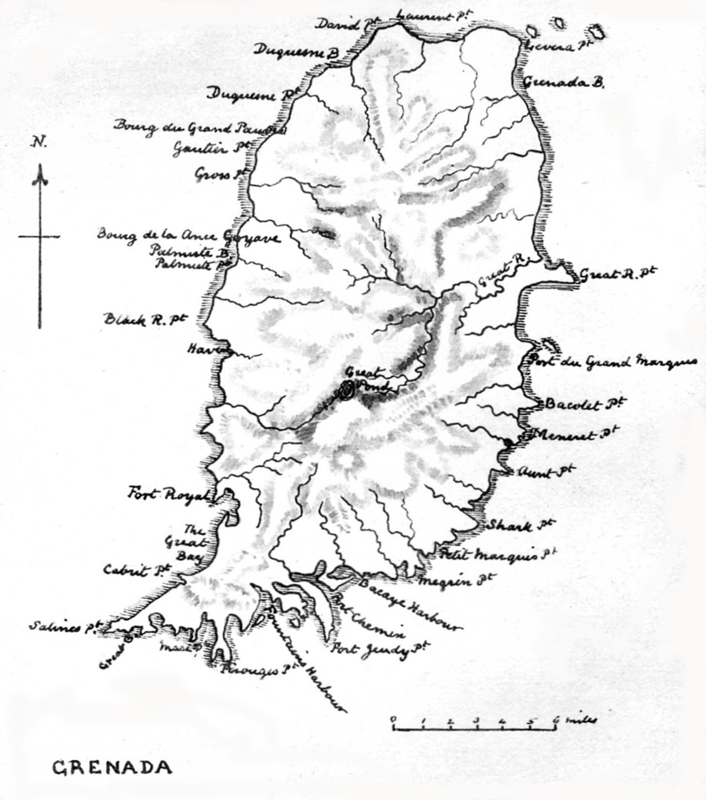

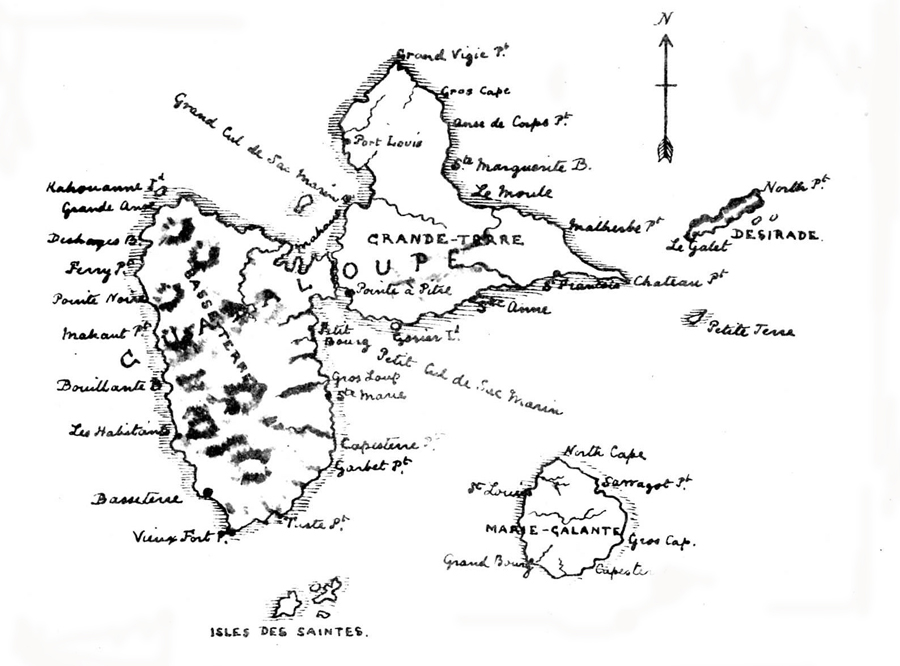

| 5. GUADALOUPE | 133 |

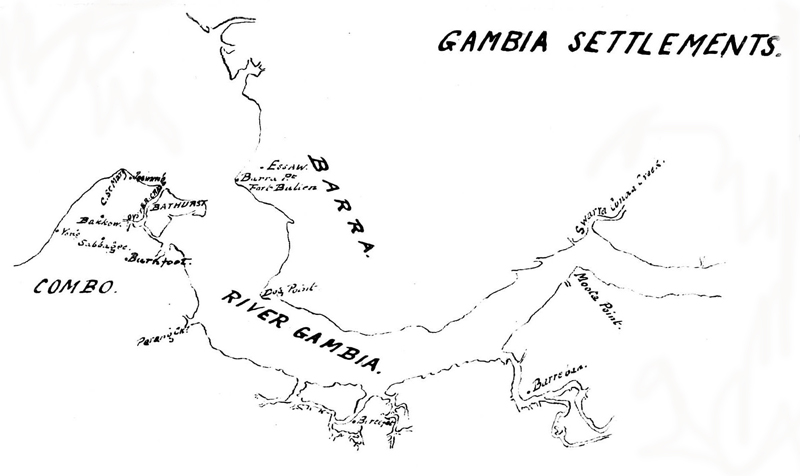

| 6. THE GAMBIA SETTLEMENTS | 178 |

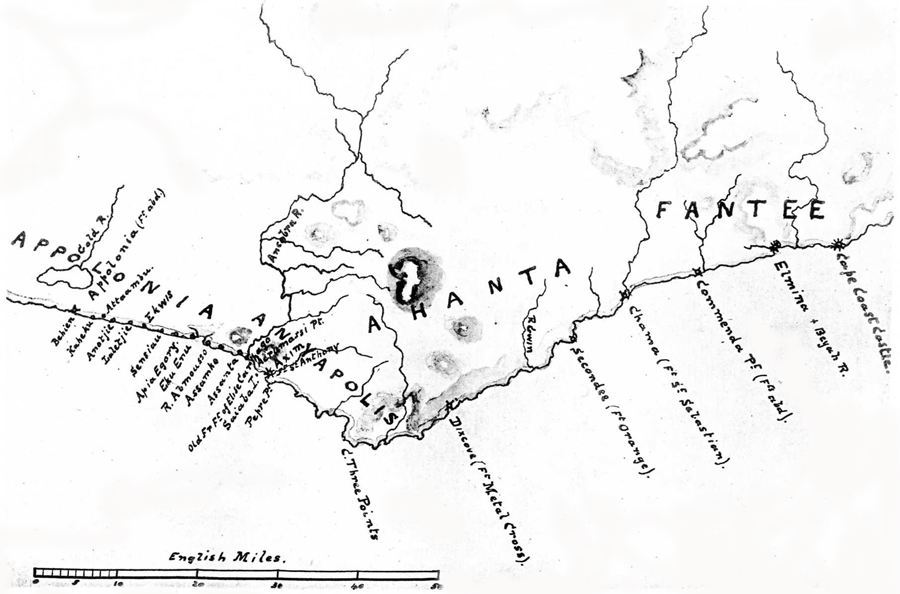

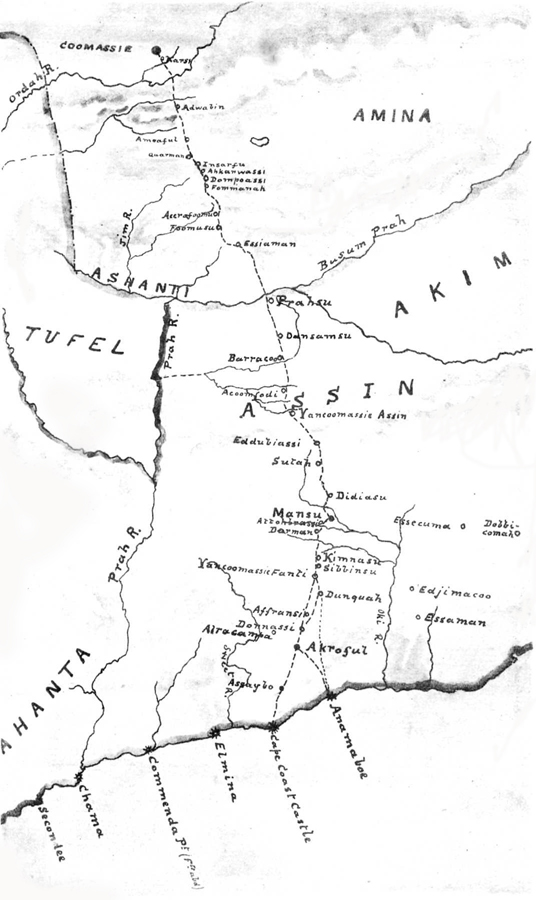

| 7. THE GOLD COAST | 215 |

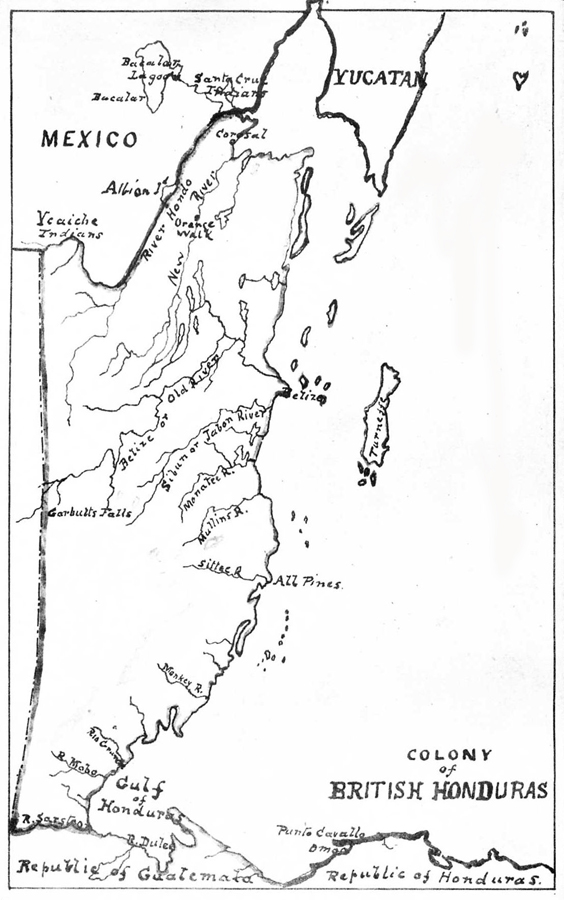

| 8. BRITISH HONDURAS | 219 |

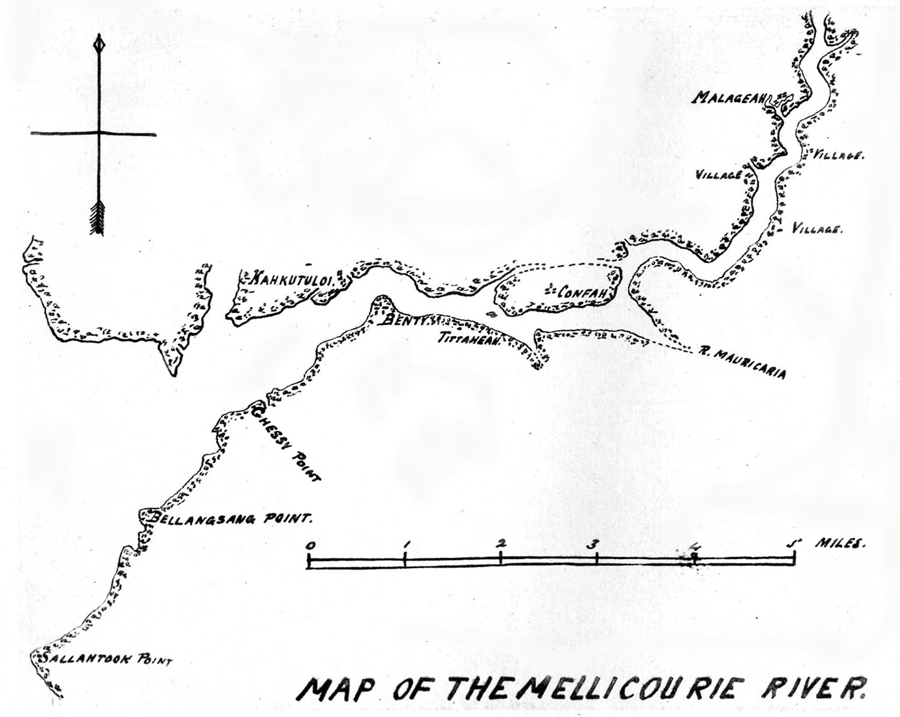

| 9. THE MELLICOURIE RIVER | 236 |

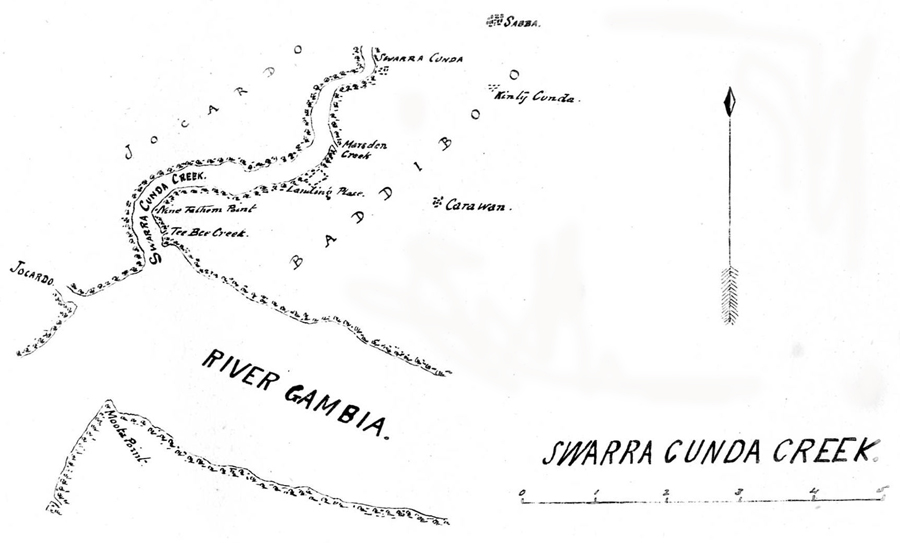

| 10. SWARRA CUNDA CREEK | 265 |

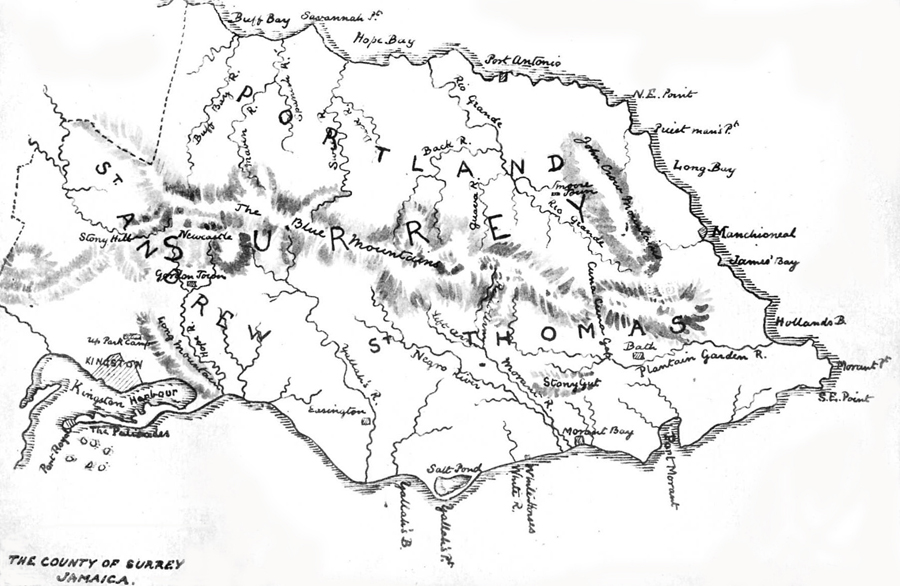

| 11. THE COUNTY OF SURREY, JAMAICA | 287 |

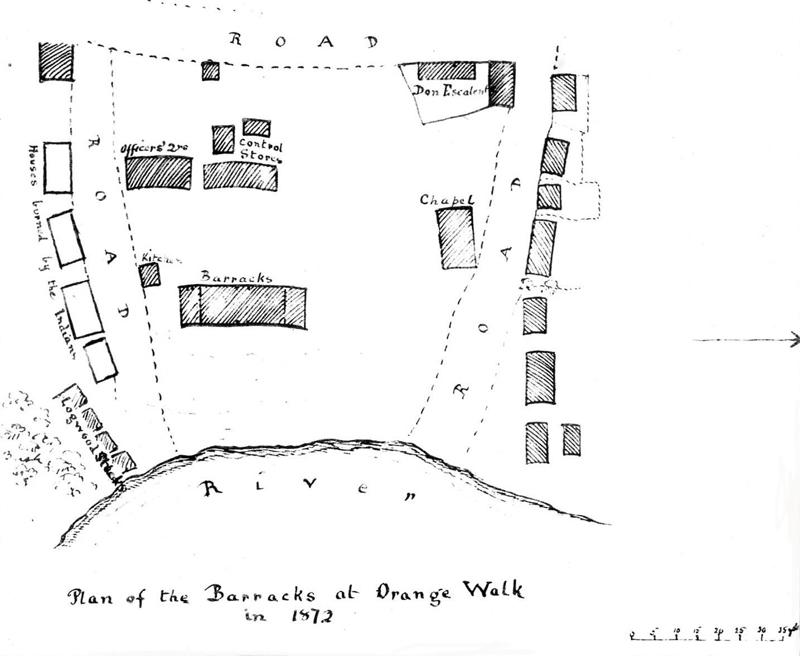

| 12. ORANGE WALK | 305 |

| 13. THE ROUTE TO COOMASSIE | 319 |

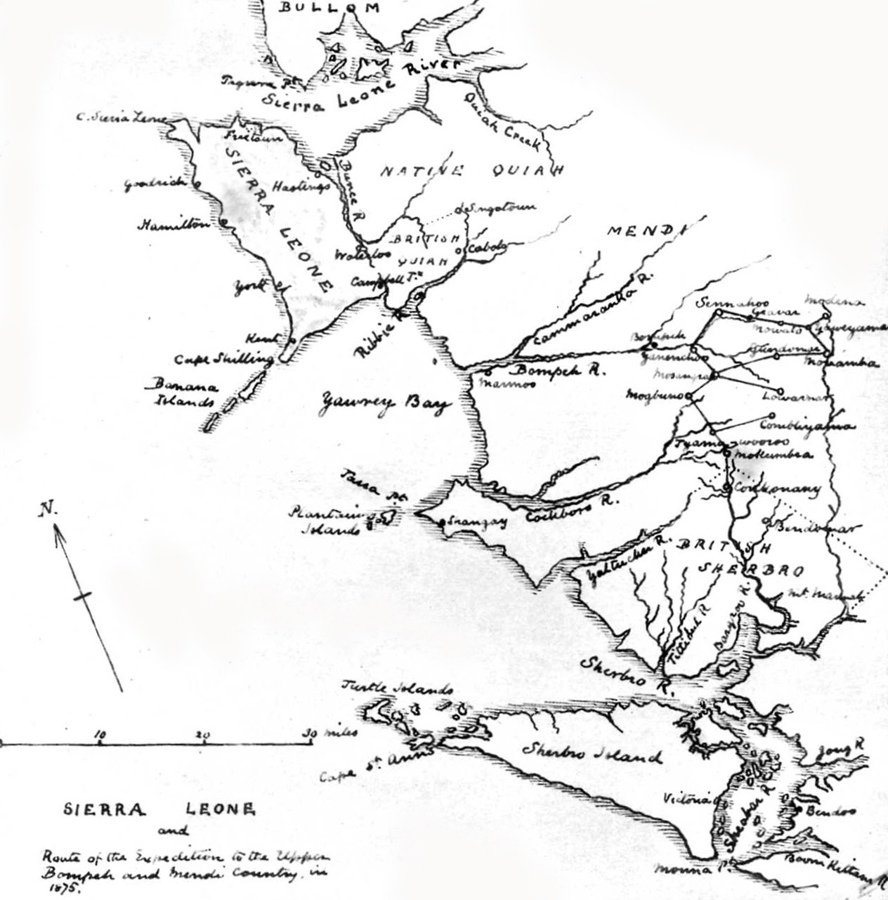

| 14. BRITISH SHERBRO | 337 |

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER.

At the present day, when our Continental neighbours are outvying each other in the completeness of their military organisations and the size of their armies, while in the United Kingdom complaints are daily heard that the supply of recruits for the British Army is not equal to the demand, it may not be out of place to draw the attention of the public to a source from which the army may be most economically reinforced.

The principal difficulty experienced by military reformers in their endeavours to remodel the British Army on the Continental system, is that caused by the necessity of providing troops for the defence of our vast and scattered Colonial Empire. Without taking into consideration India, our European and North American possessions, a considerable portion of the army has to be employed in furnishing[Pg 2] garrisons for the Cape Colony, Natal, Mauritius, St. Helena, the Bermudas, the West Indies, Burmah, the Straits Settlements, Hong Kong, etc.; which garrisons, though creating a constant drain on the Home Establishment, are notoriously inadequate for the defence of the various colonies in which they are placed; and the result is that, whenever a colonial war breaks out, fresh battalions have to be hurriedly sent out from the United Kingdom at immense expense, and the entire military machine is temporarily disarranged.

In size, and in diversity of subject races, the British Empire may be not inaptly compared with that of Rome in its palmiest days; and we have, in a measure, adopted a Roman scheme for the defence of a portion of our dominions. The Romans were accustomed, as each new territory was conquered, to raise levies of troops from the subject race, and then, most politicly, to send them to serve in distant parts of the Empire, where they could have no sympathies with the inhabitants. In India we, like the Romans, raise troops from the conquered peoples, but, unlike them, we retain those troops for service in their own country. The result of this attempt to modify the scheme was the Indian mutiny.

The plan of a local colonial army was, however, first tried in the West Indies. At the close of the last century, when the West India Islands, or the Plantations, as they were then called, were of as much importance to, and held the same position in, the British Empire as India does now,[Pg 3] there was in existence a West India Army, consisting of twelve battalions of negro troops, raised exclusively for service in the West Indies.

As India was gradually conquered, and the West India trade declined (from the abolition of the slave trade and other causes), the West India Colonies, by a regular process, fell from their former pre-eminent position. Each step in the descent was marked by the disbandment of a West India regiment, until, at the present day, two only remain in existence; and it is a matter of common notoriety that those two are principally preserved to garrison Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast Colony, British Honduras, and British Guiana—colonies the climates of which, experience has shown, are fatal to European soldiers, who are necessarily in time of peace, from the nature of their duties, more exposed to climatic influence than are officers. Economy was, of course, the cause of this continued process of reduction, for, until recently, such gigantic military establishments as those of Germany, Russia, and France were unheard of; and Great Britain was satisfied, and felt secure, with a miniature army, a paper militia, and no reserve. All this is now changed, and the necessity of an increase in our defensive power is admitted.

These negro West India troops won the highest encomiums from every British commander under whom they served. Sir Ralph Abercromby in 1796, Sir John Moore in 1797, Lieutenant-General Trigge in 1801, Sir George[Pg 4] Provost in 1805, Lieutenant-General Beckwith and Major-General Maitland in 1809 and 1810, all testified to the gallantry, steadiness, and discipline of the negro soldiers. Sir John Moore, speaking of the new corps in 1796, said "they are invaluable," and "the very best troops for the climate." To come to more recent times, in 1873 the 2nd West India Regiment bore for six months the entire brunt of the Ashanti attack, and had actually forced the invading army to retire across the Prah before the men of a single line battalion were landed. In fact, the efficiency of West India troops was, and is, unquestioned.

This being so, it may be asked, why should not the present number of regiments composed of negro soldiers be increased for the purpose of garrisoning the colonies, especially those of which the climate is most prejudicial to English soldiers? This would not be a return to the former state of affairs, for when we had twelve negro regiments they were all stationed in the West Indies, whereas the essence of the present scheme is to send them on service in other colonies. Such an augmentation of our West India, or Zouave, regiments certainly appears politic and easy. I will also endeavour to show that it would be economical.

Each West India battalion would take the place of a Territorial battalion now serving abroad. The latter would return to the United Kingdom, be reduced to the Home Establishment, and have from 300 to 400 men[Pg 5] passed into the Reserve. Repeat this process seven or eight times, and the services with the colours of between 2000 and 3000 European soldiers are dispensed with, the Reserve being increased by that number. In addition, negro soldiers being enlisted for twelve years' service with the colours, negro regiments on foreign service would not require those large drafts sent to white battalions to replace time-expired men, transport for which so swells the army estimates; while the negro being a native of the tropics, invaliding home would be reduced to a minimum.

The pay of the black soldier is ninepence per diem, against a shilling per diem to the white, so that there would be some saving effected in that way. In fact, it has been calculated that for an annual addition to the army estimates of some £27,000, six new negro battalions, each 800 strong, could be maintained; giving, on the one hand, an addition of 4800 to our present military force, and on the other, an increased Reserve, and six more Territorial battalions in the United Kingdom, ready to hand on a European emergency. To this may be added the lives of scores of Englishmen yearly saved to their country.

By the Territorial scheme now in force in Great Britain, an attempt has been made to localise corps on the German system, irrespective of the fact that Germany has no colonies, while those of Great Britain are most numerous. In Germany, in time of peace, each army corps is located in a district, from which it never moves, and in which the[Pg 6] Reserve men, destined to complete the regiments to war strength, are compelled to live. Thus, when a general mobilisation takes place, the men are on the spot, and join the regiments in which they have already served. France has adopted this system, with the exception that army corps are not permanently located in districts, and the army thus localised is the one for European service only. For her colonies an entirely distinct army is maintained, composed of men specially enlisted for foreign service. In Great Britain we have neither adopted the German system nor the French modification of that system; but a scheme of localisation, with the main-spring of localisation removed, has been endeavoured to be grafted upon our old system, under which the regular army is sent on service in time of peace to distant portions of the globe. Should the mobilisation of an army corps be necessary in England, the Reserve men would, in a large number of cases, find the regiments in which they had formerly served, on foreign service. It would then be necessary to draft them into regiments to which they were strangers, in which they would take no interest, and where they would be unknown to their officers. On the other hand, should it be necessary to despatch suddenly six or seven battalions to India or the Cape, they have to be made up to a war strength from other corps, for they have been reduced to a skeleton establishment in order that men may be provided for the Reserve.[Pg 7]

Localisation, to be effectual, must be thorough; but it and the demands of foreign service are so incompatible that they cannot be efficiently combined. At the present time, neither is said to be in a satisfactory condition, and the Reserve, which was expected to have risen to a total of 80,000 men, consists of 32,000 only.

Military reformers have long since arrived at the conclusion that if the British Army is to be maintained at such a footing as to give weight to the voice of Great Britain in the councils of Europe, we must have two distinct armies; namely, one for home service, ready for a European imbroglio, and a second to which the defence of the colonies can be entrusted. The objection to this has been, hitherto, the great expense, for it has always been taken for granted that this Colonial Army would consist of white soldiers; and the question of increased pay, supply of recruits, and periodical removal of men to the United Kingdom, over and above the cost of the Territorial Army, had to be considered. With negro troops, however, for the Colonial Army, this objection, if it does not entirely disappear, is reduced at least by three-quarters. Should it be tried on a small scale and found successful, there need be no reason why in time almost the whole of the Territorial battalions should not be withdrawn from foreign service. In this way localisation could be made a reality; and with such vast untouched recruiting grounds as our colonies offer, there can be no doubt as to the practicability of raising the negro regiments required. Such[Pg 8] regiments might also partly compose the garrisons of Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus, Aden, and Ceylon. There is, indeed, no reason, except the hatred of the Hindoo for the negro, why such regiments might not serve in India. As the negro would never coalesce with the natives of India, a new and entirely reliable force, indifferent to tropical heat, and not requiring a vast retinue of camp-followers, would be always at hand. Of course, negro battalions could never be employed in cold latitudes, for the negro suffers from cold in a manner which is incomprehensible even to Europeans who have passed the best part of their lives in the tropics. Instead of being braced by and deriving activity from the cold, he becomes languid and inert; and nothing but the rays of the sun can arouse him to any exertion. Even in West Africa, during the Harmattan season, natives may be observed in the early morning, hugging their scanty clothing around them and shivering with cold; while the ill-fated expedition to New Orleans showed what deadly havoc an inclement climate will play with negro troops.

Next, as to the men of whom these negro regiments would be composed. It is too much the custom in Great Britain, in describing a man of colour, to consider that all has been said that is necessary when he is called a negro; yet there are as many nationalities, and as many types of the African race, as there are of the Caucasian. No one would imagine that a European was sufficiently described by the title of "white man." It would be asked if the individual in[Pg 9] question were an Englishman, German, Frenchman, and so on; and the same kind of classification is necessary for the negro. On the western coast of Africa, the portion of the African continent from which North and South America and the West Indies obtained their negro population, there are at least twenty different varieties of the African race, distinct from each other in features and even in colour; and these are again subdivided into several hundred nations or tribes, each of which possesses a language, manners, and customs of its own.

In the days of the slave-trade, the slave-dealers adopted certain arbitrary designations to denote from what portion of the coast their wares were obtained. For instance, slaves shipped from Sierra Leone and the rivers to the north and east of that peninsula, and who were principally Timmanees, Kossus, Acoos, Mendis, Foulahs, and Jolloffs, were called Mandingoes, from the dominant tribe of that name which supplied the slave-market. Negroes from the Gold Coast kingdoms of Ashanti, Fanti, Assin, Akim, Wassaw, Aquapim, Ahanta, and Accra were denominated Koromantyns, or Coromantees, a corruption of Cormantine, the name of a fort some sixteen miles to the east of Cape Coast Castle, and which was the earliest British slave-station on the Gold Coast. Similarly, slaves from the tribes inhabiting the Slave Coast, that is to say, Awoonahs, Agbosomehs, Flohows, Popos, Dahomans, Egbas, and Yorubas, were all termed Papaws; while those from the[Pg 10] numerous petty states of the Niger delta, where the lowest type of the negro is to be found, were known as Eboes.

Thousands of men of these tribes, and others too numerous to mention, were carried across the Atlantic and scattered at hap-hazard all over the West India Islands. At first tribal distinctions were maintained, but in the course of years, in each island they gradually disappeared and were forgotten; until at the present day a West India negro does not describe himself as a Kossu or a Koromantyn, but as a Jamaican, a Barbadian, an Antiguan, etc. It would naturally be supposed that as the West India Islands all received their slave population in the same manner, and that as in each there was the same original diversity of nationalities, subsequently blended together by intermarriages and community of wants and language, a West India negro of the present generation from any one island would be hardly distinguishable from one from any other. Nothing, however, would be further from the truth. Since the abolition of slavery, the conditions of life in the various islands have been so different—in some the dense population necessitating daily labour for an existence, while in others large uncultivated stretches of wood and mountain have afforded squatting grounds for the majority of the black population—that, in conjunction with diversity of climate, each group of islands is now populated with a race of negroes morally distinct per se. The difference between a negro born and bred in Barbados and one born and bred in Jamaica is[Pg 11] as great as between an American and an Englishman, and the clannish spirit of the negro tends to increase that difference. At the present time the negro of Jamaica does not care to enlist in the 2nd West India Regiment, which is largely recruited in Barbados; and, in the same way, the Barbadian declines to serve in the 1st West India Regiment, because it is almost entirely composed of Jamaicans.

While the negroes of the West Indies have thus lost all their tribal peculiarities in the natural course of progress and civilisation, those of West Africa have remained at a standstill; and there is to-day as much difference between the hideous and debased Eboe and the stately and dignified Mandingo, between the docile Fanti and the bloodthirsty Ashanti, as there was one hundred and fifty years ago. Civilising influences have made this contrast between the Africans and their West India descendants still more striking. The latter have, since the abolition of slavery, been living independent lives, in close contact with civilisation, and enjoying all the rights of manhood under British laws. From their earliest infancy they have known no language but the English, and no religion but Christianity; while the former are still barbarians, grovelling in fetishism, cursed with slavery, ignorant, debased, and wantonly cruel. The West India negro has so much contempt for his African cousin, that he invariably speaks of him by the ignominious title of "bushman." In fact, the former considers himself in every respect an Englishman, and the anecdote of the[Pg 12] West India negro, who, being rather roughly jolted by a Frenchman on board a mail steamer, turned round to him and ejaculated, "I think you forget that we beat you at Waterloo," is no exaggeration.

Just as the negro races of West Africa are distinct from one another, and the West India negro from all, so are the coloured inhabitants of both those parts of the world entirely distinct from the Kaffir tribes of South Africa; and a coalition between Galeka or Zulu inhabitants and West India troops would be as impossible as the fraternisation of a Territorial battalion with the natives of India. Apart, however, from the fact that negro troops could always be safely employed alone outside the colony in which they were bred, history has shown that the fidelity of West India soldiers is beyond question. Indeed it would be difficult to say what stronger ties there could be than those of sentiment, language, and religion, and the association from childhood with British manners, customs, laws, and modes of thought. When to these are added discipline, the habit of obedience, and that well-known affection for their officers and their regiment which is so particularly an attribute of the West India soldier, it must be acknowledged that the guarantees of fidelity are, with the single exception of race, at least as good as those of the linesmen.

In India, the native army consists of men hostile to us by tradition, creed, and race, who consider their food defiled if even the shadow of a British officer should chance to[Pg 13] fall across it, and assuredly it would be as safe a proceeding to garrison our colonies with English negroes as to garrison India with such men. Yet that is done at the present day, and excites no remark.

The English-speaking negro of the West Indies is most excellent material for a soldier. He is docile, patient, brave, and faithful, and for an officer who knows how to gain his affection—an easy matter, requiring only justness, good temper, and an ear ready to listen patiently to any tale of real or imaginary grievance—he will do anything. Of course they are not perfect; they have their faults, like all soldiers, and when they chance to be commanded by an officer who is unnecessarily harsh, or who speaks roughly to them, they manifest their displeasure by passive obedience and a stubborn sullenness. English soldiers, on the other hand, under such circumstances, proceed to acts of insubordination, and it is for military judges to say which mode of expression they prefer.

The West African negro does not appear to such advantage as a soldier. Although all the specimens, with the exception of the Sierra Leone negro, possess the first necessary qualification of personal courage, they are dull and stupid, and cannot be transformed into intelligent soldiers. It may be wondered why the Sierra Leonean, who alone among the West Africans is an English-speaking negro, should be worse than his more barbarian neighbours; but I believe the solution may be found in the fact that[Pg 14] the large proportion of slaves landed in former days at Sierra Leone from captured slavers were so-called Eboes, from the tribes of the Niger delta; which tribes all ethnologists are agreed in describing as among the lowest of the African races, and which, it may be remarked, are even at the present day addicted to cannibalism. The West African soldier is a mere machine, who mechanically obeys orders, and never ventures, under any circumstances, to act or think for himself. Should an African be placed on sentry, he fulfils to the letter the orders read to him by the non-commissioned officer who posts him, but frequently entirely ignores their spirit. Sometimes this is productive of amusing incidents. For instance, some years ago, among the orders for the sentry posted at Government House, Sierra Leone, was one to the effect that no one was to be permitted to leave the premises after dark carrying a parcel. This order had been issued at the request of the Governor, to prevent pilfering on the part of his servants. One evening the Governor was coming out of his house with a small despatch-box, when, to his surprise, he was stopped by the sentry, an old African.

"But I'm the Governor," said the astonished administrator, "and I had that order made myself. You mustn't stop me."

"Me no care if you be Gubnor or not," replied the imperturbable African. "The corporal gib de order, and you no can pass." And Her Majesty's representative had to turn back and leave his despatch-box at home.[Pg 15]

The greatest objection to the African, however, is the strange fact that no amount of care or attention on the part of his instructors can ever make him a good or even a fair shot. In the 1st West India Regiment there are still a few Africans remaining, most of whom have from twelve to eighteen years' service; and who have annually expended their rounds without hitting the target more than once or twice during the whole musketry course. Give these men a rifle rested on a tripod, and tell them to align the sights upon some given mark, and they cannot do it. They will frequently aim a foot or two to the right or left of an object only a few yards distant. Every possible plan has been tried to make them improve, but all have equally failed; and, in consequence, Africans are not now enlisted. Still, although on account of this failing, African troops could never, in these days of long-range firing, meet Europeans in the field, a battalion of Africans would be quite good enough for bush fighting against an enemy like the Ashanti, a still worse marksman, and worse armed; or against tribes armed with the spear or assegai.

Of course one reason of the African's dulness is that until he enlists, that is until he is from twenty-four to thirty years of age, he has never exercised his mind in any way; and the long years of mental idleness have produced a sluggishness which makes it extremely difficult for him to acquire anything new that requires thought. After enlisting, he picks up a species of unintelligible English, but that is[Pg 16] the most that he can do. It is pitiful to see these men, some of them now old, struggling day after day, according to regulation, in the regimental school, to learn their letters. It is to them the greatest punishment that could be inflicted, and though they attend school for years, they rarely succeed in doing more than master the alphabet.

In former days, whenever the cargo of a captured slaver was landed at Sierra Leone, a party from the garrison used to be admitted to the Liberated African Yard for the purpose of seeking recruits amongst the slaves. Many of the latter, pleased with the brilliant uniform, and talked over by the recruiting party, who were men specially selected for this duty on account of their knowledge of African languages, offered themselves as recruits. If medically fit, they were invariably accepted, though it must have been well known that they could not possibly have had any idea of the nature of the engagement into which they were entering. Some fifteen or twenty recruits being thus obtained, they were given high-sounding names, such as Mark Antony, Scipio Africanus, etc., their own barbaric appellations being too unpronounceable, and then marched down in a body to the cathedral to be baptised. Some might be Mohammedans, and the majority certainly believers in fetish, but the form of requiring their assent to a change in their religion was never gone through; and the following Sunday they were marched into church as a matter of course, along with their Christian comrades. Although thus nominally christianised,[Pg 17] they still remained at heart believers in fetish, for it is a remarkable fact that no adult West African has ever become a bonâ-fide convert, and the missionaries have long since given up attempting to proselytise grown persons, reserving all their efforts for children. Holding, as they did, in great dread all fetish, or obeah, practices; usually someone amongst them, more cunning than the rest, professed an acquaintance with the supposed diabolical ritual; and gained influence with, and extorted money from, his more timid comrades. Officers now in the 1st West India Regiment can remember the time when, there being many Africans in the regiment, the feathers of parrots or scraps of rags might be found in the neighbourhood of the orderly room. Whenever this was the case, it was known that an African was about to be brought before his commanding officer for some neglect of duty or breach of discipline; and these fetishes had been placed there to induce the colonel to deal leniently with the offender. Ridiculous as this practice must seem to every educated person, it sometimes produced the most serious effects upon the credulous Africans; and I have heard old officers speak of instances, which came within their own knowledge, of soldiers who, having found old bones, broken pieces of calabashes, or glass, placed on their beds, immediately resigned themselves to death, saying that "fetish was thrown upon them," and in nine cases out of twelve, so certain were they that it was impossible to escape the coming doom, they positively frightened or worried them[Pg 18]selves to death. The professors of fetishism likewise drove a good trade in amulets which rendered the wearer invulnerable. On one occasion at Sierra Leone, a young African who had been recently enlisted displayed with much pride a gri-gri or amulet which he wore on his wrist, and which, he asserted, rendered him invulnerable. His West India comrades laughed at him; and the African, indignant at the doubt thrown upon the efficacy of his charm, drew his knife, and, before he could be stopped, plunged it into his thigh to prove that he spoke the truth. His eyes were opened, unfortunately, too late; for though he was at once removed to the hospital, he died from the effects of this self-inflicted wound. In West India regiments the practice of fetish was made a military crime, and was severely punished. Sufferers or imaginary sufferers from fetishism, however, rarely complained to their officers, for they believed that the occult art practised by the professor was superior to any power held by man, and consequently, culprits were but seldom detected. With the disappearance of Africans from West India regiments, the offence of fetishism has, however, also disappeared.

Military crime in West India regiments is of comparatively rare occurrence. Even when the 3rd West India Regiment was in existence, there was less in the three negro regiments than in one of the Line; while drunkenness is confined to the few black sheep who will be found in every body of men. Riots or disturbances between West India[Pg 19] soldiers and the inhabitants of the towns in which they are quartered are unheard of, and in every garrison they receive the highest praise for their unvarying good and quiet behaviour. In fact they are merry, good-tempered, and orderly men, who do not wish to interfere with anyone; and, owing to their temperate habits, they are not led into the commission of offences by the influence of drink. Of course, the popular idea in Great Britain of the negro is that he is a person who commonly wears a dilapidated tall hat, cotton garments of brilliant hue, carries a banjo or concertina, and indulges in extraordinary cachinnations at the smallest pretext; but this is as far from the truth as the creature of imagination in the opposite extreme, evoked by the vivid fancy of Mrs. Beecher Stowe.

The bravery of the West India soldier in action has often been tested, and as long as an officer remains alive to lead not a man will flinch. His favourite weapon is the bayonet; and the principal difficulty with him in action is to hold him back, so anxious is he to close with his enemy. It is unnecessary here to refer to individual acts of gallantry performed by soldiers of the 1st West India Regiment, they being fully set forth in the following history; but of such performed by soldiers of other West India regiments the two following now occur to me.

Private Samuel Hodge, a pioneer of the 3rd West India Regiment, was awarded the Victoria Cross for conspicuous bravery at the storming of the Mohammedan stockade at[Pg 20] Tubarcolong (the White Man's Well), on the River Gambia, on the 30th of May, 1866. Under a heavy fire from the concealed enemy, by which one officer was killed and an officer and thirteen men severely wounded, Hodge, and another pioneer named Boswell, chopped and tore away with their hands the logs of wood forming the stockade, Boswell falling nobly just as an opening was effected. Again, in 1873, during the Ashanti War—when it was reported, on the 5th of December, by natives at Yancoomassie Assin that the Ashanti army had retired across the Prah—two soldiers of the 2nd West India Regiment volunteered to go on alone to the river and ascertain if the report were true. On their return they reported all clear to the Prah; and said they had written their names on a piece of paper and posted it up. Six days later, when the advanced party of the expeditionary force marched into Prahsu, this paper was found fastened to a tree on the banks of the river. At the time that this voluntary act was performed it must be remembered that, on the 27th of November, the British and their allies had met with a serious repulse at Faisowah, through pressing too closely upon the retiring Ashantis; that this repulse was considered both by the Ashantis and by our native allies as a set-off against the failure of the attack on Abracampa; that the Houssa levy was in a state of panic, and no reliable information as to the position of the enemy was obtainable. It was under such circumstances that these two men advanced nearly sixteen miles into an (to them)[Pg 21] unknown tract of solitary forest, to follow up an enemy that never spared life, and whose whereabouts was doubtful.

Other qualifications apart, however, West India troops have proved themselves of the very greatest value on active service in tropical climates from the very fact that, being natives of the tropics, they can undergo fatigue and exposure that would be fatal to European soldiers. In campaigns in which both the West India and the European soldier are employed, all the hard and unpleasant work is thrown upon the former, and the publication in general orders of the thanks of the officer in command of the force is the only acknowledgment he receives; for newspaper correspondents, naturally anxious to swell the circulation of the journals they represent, while giving the most minute details of the doings of the white soldier, leave out in the cold his black comrade, who has few friends among the reading public of Great Britain. Occasionally, facts are even misrepresented. For instance, the defence of Fommanah, on the 2nd of February, 1874, which was really effected by a detachment of the 1st West India Regiment, was, in an account telegraphed to one London daily paper, attributed to the 23rd Regiment, of which corps there were only six or seven men in the place, and those in hospital.

On the last occasion on which West India troops served with Line battalions, namely in the Ashanti War of 1873-74, West India soldiers daily marched twice and even three times the distance traversed by the white troops; and, south[Pg 22] of the Prah, searched the country for miles on both sides of the line of advance, in search of carriers. It is not too much to say, that if the two West India regiments had not been on the Gold Coast, no advance on Coomassie would, that year, have been possible. In December, 1873, the transport broke down; there was a deadlock along the road; each half-battalion of the European troops was detained in the camp it occupied, and the 23rd Regiment had to be re-embarked for want of carriers. The fate of the expedition was trembling in the balance, and the control officers were unanimous in declaring that a further advance was impossible, and that the troops in front would have to return by forced marches. Prior to this, the want of transport had been felt to such an extent that the West India soldiers had been placed on half rations; a step, however, which was not followed by any diminution of work, which remained as hard as ever. In this emergency the two West India regiments, with the 42nd—to whom all honour be due—volunteered to carry supplies, in addition to their arms, accoutrements, and ammunition. They acted as carriers for several days, and moved such quantities of provisions to the front that the pressure was removed and a further advance made possible. Even if more carriers had been obtained from the already ransacked native villages, they could not have arrived in time, for the rainy season was fast approaching and the delay of a fortnight would have been fatal.[Pg 23]

There was a peculiar irony of fate in the expedition being thus relieved of its most pressing difficulties through the exertions of the West India regiments. It had been Sir Garnet Wolseley's original intention to take into Ashanti territory only the Rifle Brigade, the 23rd, and the 1st and 2nd West India Regiments; and, on the arrival of the hired transport, Sarmatian, he wrote, on the 15th of December, that he did not propose landing the 42nd. In the course of the next three days, however, he changed his views, and, in his letter of the 18th December, gave as his reason: "I find that the one great obstacle to the employment of a third battalion of English troops, viz., the difficulty of transport, is as great in the case of a West India regiment. The West India soldier has the same rations as the European soldier, and a West India regiment requires, man for man, exactly the same amount of transport as a European regiment." The 42nd, therefore, was to be landed and taken to the front, while the 1st West India Regiment was to remain at Cape Coast Castle and Elmina as a reserve. Afterwards, when the transport failed, it was found that the West India soldier could do the work of the European on half rations, and carry his own supplies as well.

West India regiments at the present day labour under many disadvantages. Owing to the two battalions having to furnish garrisons for colonies which really require three, they are alternately for one period of three years divided[Pg 24] into three detachments, and for the next period of three years into six. No lieutenant-colonel of a West India regiment can ever see the whole of his regiment together. The largest number that, under present circumstances, he can ever have under him at any one station is four companies; and the most he can have under his actual command at any one time is six companies on board a troopship. Thus in a regiment there are sometimes three, and sometimes six, officers vested with the power of an officer commanding a detachment; and however conscientiously they may endeavour to follow out a regimental system, every individual has naturally a different manner of dealing with men, and a certain amount of homogeneousness is lost to the regiment as a whole.

Endless correspondence is entailed, and sometimes questions have to remain open for months, until answers can be received from distant detachments. In small garrisons, also, drill becomes a mere farce; for, after the clerks, employed men, and men on guard and in hospital are deducted, there are perhaps only a dozen men or so left for parade. In spite of all these drawbacks the regiments still maintain a wonderful efficiency, and afford another proof of the soldierlike qualities of the West India negro.

Another disadvantage is that a West India regiment is never seen in England, the British public knows nothing of such regiments, has no friends, relatives, or acquaintances in their ranks, and consequently takes no interest in them.[Pg 25] Yet they are a remarkably fine body of men, and a picked battalion of the Guards would look small beside them if brigaded with them in Hyde Park. So little is known, that I have sometimes been asked if the officers of West India regiments are also black, and it is with a view to making the regiment to which I have the honour to belong better known to the public at large, that the following history has been written. There has been no attempt at descriptive writing, facts being merely collected from official documents, so that the authenticity of the narrative may be unquestionable.

In order that the earlier chapters may be the more readily understood, it may be as well to state that, with the 1st West India Regiment, which was called into existence in the London Gazette of the 2nd of May, 1795, were incorporated two other corps; of which one, the Carolina Corps, had been in existence since 1779, while the other—Malcolm's, or the Royal Rangers—had been raised in January or February, 1795. It is from the Carolina Corps that the 1st West India Regiment derives the Carolina laurel, borne on the crest of the regiment.[Pg 26]

CHAPTER I.

THE ACTION AT BRIAR CREEK, 1779—THE ACTION AT STONO FERRY, 1779.

In the autumn of 1778, during the War of the American Independence, the British commanders in North America determined to make another attempt for the royal cause in the Southern States of Georgia and South Carolina, which, since the failure of Lord Cornwallis at the siege of Charlestown in July, 1776, had been allowed to remain unmolested. With this view they despatched Colonel Campbell, in November, from New York, with the 71st Regiment, two battalions of Hessians, three of Loyal Provincials,[1] and a detachment of Artillery, the whole amounting to about 3500, to make an attempt upon the town of Savannah, the capital of Georgia. Arriving off the mouth of the Savannah River on the 23rd of December, Colonel Campbell was so rapidly successful, that, by the middle of January, not only was Savannah in his hands, but Georgia itself was entirely cleared of American troops.

It was about this time that the South Carolina Regiment, the oldest branch of the 1st West India Regiment, was raised. Numerous royalists joined the British camp and were formed into various corps;[2] and the South Carolina Regiment is first mentioned as taking part in the action at Briar Creek on the 3rd of March, 1779,[3] the corps then being, according to Major-General Prevost's despatch, about 100 strong. The action at Briar Creek occurred as follows:

In the early part of 1779, General Prevost's[4] force was distributed in posts along the frontier of Georgia; Hudson's Ferry, twenty-four miles above Savannah, being the upper extremity of the chain. Watching these posts was the American general, Lincoln, with the main body of the American Army of the South, at Purrysburgh, about twenty miles above Savannah, and General Ashe, who was posted with about 2000 of the Militia of North and South Carolina and Georgia, at Briar Creek, near the point where it falls into the Savannah River.

General Ashe's position appeared most secure, his left being covered by the Savannah with its marshes, and his front by Briar Creek, which was about twenty feet broad,[Pg 28] and unfordable at that point and for several miles above it; nevertheless, General Prevost determined to surprise him. For the purpose of amusing General Lincoln, he made a show of an intention to pass the river; and, in order to occupy the attention of Ashe, he ordered a party to appear in his front, on the opposite side of Briar Creek. Meanwhile General Prevost, with 900 chosen men, made an extensive circuit, passed Briar Creek fifteen miles above the American position, gained their rear unperceived, and was almost in their camp before they discovered his approach. The surprise was as complete as could be wished. Whole regiments fled without firing a shot, and numbers without even attempting to seize their arms; they ran in their confusion into the marsh, and swam across the river, in which numbers of them were drowned. The Continental troops, under General Elbert, and a regiment of North Carolina Militia, alone offered resistance; but they were not long able to maintain the unequal conflict, and, being overpowered, were compelled to surrender. The Americans lost from 300 to 400 men, and seven pieces of cannon. The British lost five men killed, and one officer and ten men wounded.

After this success, the British and American forces remained on opposite sides of the River Savannah, until the end of April, when General Lincoln, thinking the swollen state of the river and the inundation of the marshes was sufficient protection for the lower districts, withdrew his forces further inland, leaving General Moultrie with 1000[Pg 29] men at Black Swamp. By this movement Lincoln left Charlestown exposed to the British. General Prevost at once took advantage of this, and, on the 29th of April, suddenly crossed the river, near Purrysburgh, with 2500 men, among whom was the South Carolina Regiment, which had been considerably increased by accessions of loyalists and freed negroes.

General Prevost advanced rapidly into the country, the militia under Moultrie, who had considered the swamps impassable, offering but a feeble resistance, and retiring hastily, destroying the bridges in their rear. On the 11th of May, the British force crossed the Ashley River a few miles above Charlestown, and, advancing along the neck formed by the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, established itself at a little more than cannon-shot from the city. A continued succession of skirmishes took place on that day and the ensuing night, and on the following morning Charlestown was summoned to surrender.

Negotiations were broken off in the evening, much to the disappointment of the British general, who had been led to suppose that a large proportion of the inhabitants were favourable to the royal cause, and that the city would fall easily into his hands. He now found himself in a dangerous predicament. He was without siege guns, before lines defended by a considerable force of artillery, and flanked by shipping; he was involved in a labyrinth of creeks and rivers, where a defeat would have been fatal, and General Lincoln[Pg 30] with a force equal, if not superior to his own, was fast approaching for the relief of the city. Taking all this into consideration, General Prevost prudently struck camp that night, and, under cover of the darkness, the direct line of retreat on Savannah being closed, returned to the south side of the Ashley River. From thence the army passed to the islands of St. James and St. John, lying to the southward of Charlestown harbour, and commencing that succession of islands and creeks which extends along the coast from Charlestown to Savannah.

In these islands the army awaited supplies from New York, of which it was much in need; and, on the arrival of two frigates, it commenced to move to the island of Port Royal, which at the same time would afford good quarters for the troops during the intense heats, and, from its vicinity to Savannah, and its excellent harbour, was the best position that could be chosen for covering Georgia.

Directly General Lincoln discovered what was taking place, he advanced to attack. St. John's Island is separated from the mainland by a narrow inlet, called Stono River, and communication between the mainland and the island was kept up by a ferry. On the mainland, at this ferry, General Prevost had established a post, consisting of three redoubts, joined by lines of communication; and, to cover the movement of the army to Port Royal Island, he here posted Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland with the 1st Battalion of the 71st Regiment, a weak battalion of Hessians, the[Pg 31] North Carolina Regiment, and the South Carolina Regiment, amounting in the whole to about 800 men.

On the 20th of June, General Lincoln made a determined attempt to force the passage, attacking with a force variously estimated at from 1200 to 5000 men and eight guns. Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland's advanced posts, consisting of the South Carolina Regiment, were some distance in front of his works; and a smart firing between them and the Americans gave him the first warning of the approach of the enemy. He instantly sent out two companies of the 71st from his right to ascertain the force of the assailants. The Highlanders had proceeded only a quarter of a mile when they met the outposts retiring before the enemy. A fierce conflict ensued. Instead of retreating before superior numbers, the Highlanders persisted in the unequal combat till all their officers were either killed or wounded, of the two companies eleven men only returned to the garrison; and the British force was sadly diminished, and its safety consequently imperilled by this mistaken valour.

The whole American line now advanced to within three hundred yards of the works, and a general engagement began, which was maintained with much courage and steadiness on both sides. At length the regiment of Hessians on the British left gave way, and the Americans, in spite of the obstinate resistance of the two Carolina regiments, were on the point of entering the works, when a judicious flank movement of the remainder of the 71st[Pg 32] checked the advance; and General Lincoln, apprehensive of the arrival of British reinforcements from the island, drew off his men, and retired in good order, taking his wounded with him.

The battle lasted upwards of an hour. The British had 3 officers and 19 rank and file killed, and 4 officers and 85 rank and file wounded. The South Carolina Regiment had Major William Campbell and 1 sergeant killed, 1 captain, 1 sergeant, and 3 rank and file wounded.[5] The Americans lost 5 officers and 35 men killed, 19 officers and 120 men wounded.

Three days after the battle, the British troops evacuated the post at Stono Ferry, and also the island of St. John, passing along the coast from island to island till they reached Beaufort in the island of Port Royal. Here General Prevost left a garrison under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland, and proceeded with the remainder of his force, with which was the South Carolina Regiment, to the town of Savannah.

The heat had now become too intense for active service; and the care of the officers was employed in preserving their men from the fevers of the season, and keeping them in a condition for service next campaign, which was expected to open in October.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] De Lancey's Corps, the New York Volunteers, and Skinner's Corps.

[2] "Annual Register," 1779, Beatson's "Memoirs," Gordon's "History of the American War," etc. etc.

[3] Beatson's "Naval and Military Memoirs," vol. iv. p. 492.

[4] Major-General Prevost had come from Florida and assumed command in January.

[5] "Return of the killed, wounded, and missing at the repulse of the Rebels at Stono Ferry, South Carolina, June 20th, 1779."

CHAPTER II.

THE SIEGE OF SAVANNAH, 1779—THE SIEGE OF CHARLESTOWN, 1780—THE BATTLE OF HOBKERK'S HILL, 1781.

At the opening of the next campaign, although General Prevost had been obliged to retire from Charlestown and to abandon the upper parts of Georgia, yet, so long as he kept possession of the town of Savannah and maintained a post at Port Royal Island, South Carolina was exposed to incursions. The Americans, therefore, pressed the French admiral, Count D'Estaing, to repair to the Savannah River, hoping, by his aid, to drive the British from Georgia. D'Estaing, in compliance, sailed from Cape François, in St. Domingo; and with twenty-two sail of the line and a number of smaller vessels, having 4800 French regular troops on board and several hundred black troops from the West Indies, appeared off the Savannah so unexpectedly that the Experiment, a British fifty-gun ship, fell into his hands. On the appearance of the French fleet, on September 9th, General Prevost immediately called in all his[Pg 34] outposts in Georgia, sent orders to Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland, at Port Royal, to rejoin him at once, and exerted himself to strengthen the defences of the town of Savannah.

For the first three or four days after the arrival of the fleet, the French were employed in moving their troops through the Ossabaw Inlet to Beaulieu, about thirteen miles above the town of Savannah. On the 15th of September, the French, with a party of American light horse, attacked the British outposts, and General Prevost withdrew all his force into his works.

On the 16th, D'Estaing summoned the place to surrender. Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland's force had not yet arrived, the works were still incomplete, and General Prevost was desirous of gaining time; he consequently requested a suspension of hostilities for twenty-four hours. This was granted, and in that critical interval Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland, by the most extraordinary efforts—for one of General Prevost's messengers had fallen into the hands of the enemy, who had at once seized all the principal lines of communication—arrived with the garrison of Port Royal, and entered the town. Encouraged by this accession of strength, General Prevost now informed Count D'Estaing that he was resolved to defend the place to the last extremity. On the 17th, D'Estaing had been joined by General Lincoln with some 3000 men, which, with the French troops, raised the total besieging force to something over 8000. The besieged did not exceed 3000.[Pg 35]

The enemy spent several days in bringing up guns and stores from the fleet, and on the 23rd the besieging army broke ground before the town. On the 1st of October, they had advanced to within 300 yards of the British works. On the morning of the 4th of October, several batteries, mounting thirty-three pieces of heavy cannon and nine mortars, with a floating battery of sixteen guns on the river, opened fire on the town. For several days they played incessantly on the garrison, and there was continued skirmishing between the negroes of the Carolina regiments and the enemy.[6]

On the morning of the 9th of October, the enemy, under a furious cannonade, advanced to storm in three columns, with a force of 3000 French under D'Estaing in person, and 1500 Americans under Lincoln. General Prevost, in his despatch to Lord George Germain, dated Savannah, November 1st, 1779, says: "However, the principal attack, composed of the flower of the French and rebel armies, and led by D'Estaing in person, with all the principal officers of either, was made upon our right. Under cover of the hollow, they advanced in three columns; but having taken a wider circuit than they needed, and gone deeper in the bog, they neither came so early as they intended nor, I believe, in the same order. The attack, however, was very spirited, and for some time obstinately persevered in, particularly on the Ebenezer Road Redoubt. Two stand of colours were[Pg 36] actually planted, and several of the assailants killed upon the parapet; but they met with so determined a resistance, and the fire of three seamen batteries, taking them in almost every direction, was so severe, that they were thrown into some disorder, at least at a stand; and at this most critical moment, Major Glasier, of the 60th, with the 60th Grenadiers and the Marines, advancing rapidly from the lines, charged (it may be said) with a degree of fury; in an instant the ditches of the redoubt and a battery to its right in rear were cleared.... Lieutenant-Colonel de Porbeck, of Weissenbach's, being field officer of the day of the right wing, and, being in the redoubt when the attack began, had an opportunity, which he well improved, to signalise himself in a most gallant manner; and it is but justice to mention to your lordships the troops who defended it. They were part of the South Carolina Royalists, the Light Dragoons (dismounted), and the battalion men of the 4th 60th, in all about 100 men, commanded (by a special order) by Captain James, of the Dragoons (Lieutenant 71st), a good and gallant officer, and who nobly fell with his sword in the body of the third he had killed with his own hand."

After their repulse from the Ebenezer Redoubt, the enemy retired, and, a few days afterwards, the siege was raised, the Americans crossing the Savannah at Zubly's Ferry and taking up a position in South Carolina, while the French embarked in their fleet and sailed away. During the assault the French lost 700 and the Americans 240[Pg 37] killed. The British loss was 55, four of whom belonged to the South Carolina Regiment, who were killed in the redoubt, where also Captain Henry, of that corps, was wounded.

According to the "Journal of the Siege of Savannah," p. 39, the garrison of the redoubt in the Ebenezer Road was as follows:

28 Dismounted Dragoons.

28 Battalion men of the 60th Regiment.

54 South Carolina Regiment.

—

110

In the same work is the following: "Two rebel standards were once fixed on the redoubt in the Ebenezer Road; one of them was carried off again, and the other, which belonged to the 2nd Carolina Regiment, was taken. After the retreat of the enemy from our right, 270 men, chiefly French, were found dead; upwards of 80 of whom lay in the ditch and on the parapet of the redoubt, and 93 were within our abattis."

The strength of the South Carolina Regiment at the termination of the siege was: 1 colonel (Colonel Innes), 1 major, 4 captains, 7 lieutenants, 3 ensigns, 15 sergeants, 7 drummers, and 216 rank and file.

Nothing of note took place in Georgia and South Carolina till January, 1780, when Sir Henry Clinton arrived in the Savannah River with a force destined for the reduction of Charlestown. He had sailed from New York on the 26th of December, 1779, and, having experienced bad weather,[Pg 38] put into the Savannah to repair damages. Sir H. Clinton selected a portion of General Prevost's force at Savannah to take part in the coming operations, and among the corps so selected was the South Carolina Regiment, which is shown in the return of troops at the capture of Charlestown as "joined from Savannah."

On the 10th of February, the armament sailed to North Edisto, where the troops disembarked, taking possession of the island of St. John next day without opposition. On the 29th of March, the army reached Ashley River and crossed it ten miles above Charlestown; then, the artillery and stores having been brought over, Sir H. Clinton marched down Charlestown Neck, and, on the night of the 1st of April, broke ground at 800 yards from the American works. The garrison of the city consisted of 2000 regular troops, 1000 North Carolina Militia, and the male inhabitants of the place.

On the 9th of April, the first parallel was finished, and the batteries opened fire; and Charlestown finally capitulated, after an uneventful siege, on the 12th of May. In the "Return of the killed and wounded" during the siege, the South Carolina Regiment is shown as having had three rank and file wounded.

Sir H. Clinton sailed from Charlestown on the 5th of June, leaving Lord Cornwallis in command. The latter meditated an expedition into North Carolina, and, for the preservation of South Carolina during his absence with[Pg 39] the main body of the troops, he established a chain of posts along the frontier. One of these posts was at Ninety-six, and for its defence was detailed the South Carolina Regiment, under Colonel Innes, with Allen's corps, "the 16th and three other companies of Light Infantry."[7] Lieutenant-Colonel Balfour was then in command of the post, but was soon after relieved by Lieutenant-Colonel Cruger.

The garrison of Ninety-six remained undisturbed till September, 1780, when, Lord Cornwallis having moved into North Carolina and occupied Charlotte, Georgia was almost denuded of troops; and an American leader, Colonel Clarke, took advantage of this to attack the British post at Augusta. Lieutenant-Colonel Brown, who commanded there with 150 men, finding the town untenable, retired towards an eminence on the banks of the Savannah, named Garden Hill, and sent intelligence of his situation to Ninety-six. Lieutenant-Colonel Cruger, with the 16th and the South Carolina Regiment, at once marched to his relief. Colonel Clarke, who had captured the British guns and was besieging the garrison of Garden Hill, upon being informed of Cruger's approach raised the siege, and, abandoning the guns which he had taken, retreated so hurriedly that, though pursued for some distance, he effected his escape.

In the spring of 1781, Lord Cornwallis had again invaded North Carolina, and, having defeated the American general,[Pg 40] Greene, at Guildford Court House, had continued his march towards Virginia, expecting the enemy to make every effort to prevent the army entering that state. General Greene, however, allowed Lord Cornwallis to pass on, and then, having assembled a considerable body of troops, made a sudden descent upon the British posts in South Carolina, where Lord Rawdon had been left in command. These posts were in a line from Charlestown by the way of Camden and Ninety-six, to Augusta in Georgia. Camden was the most important, and there Lord Rawdon had taken post with 900 men.

On the 20th of April, 1781, General Greene appeared before Camden, which was a village situated on a plain, covered on the south by the Wateree, a river which higher up is called the Catawba; and below, after its confluence with the Congaree from the south, assumes the name of the Santee. On the east of it flowed Pinetree Creek; on the northern and western sides it was defended by a strong chain of redoubts, six in number, extending from the river to the creek. Lord Rawdon's force was so small that the approach of Greene to Camden necessitated the abandonment of the ferry on the Wateree, "although the South Carolina Regiment was on its way to join him from Ninety-six, and that was its direct course; he had, however, taken his measures so well as to secure the passage of that regiment upon its arrival three days after."[8]

General Greene, whose force amounted to 1200 men, determined to await reinforcements before attacking, and on the 24th of April he retired to Hobkerk's Hill, an eminence about a mile north of Camden, on the road to the Waxhaws. Here Lord Rawdon resolved to attack him, and on the morning of the 25th, with 900 men, he marched from Camden, and, by making a circuit, and keeping close to the edge of the swamp, under cover of the woods, he gained the left flank of the Americans, where the hill was most accessible, undiscovered.

The alarm was given, while the Americans were at breakfast, by the firing of the outposts, and at this critical moment a reinforcement of American militia arrived. So confident was General Greene of success that he ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Washington, with his cavalry, to turn the right flank of the British and to charge them in the rear, while bodies of infantry were to assail them in front and on both flanks.

The American advanced parties were driven in by the British after a sharp skirmish, and Lord Rawdon advanced steadily to attack the main body of the enemy. The 63rd Regiment, with the volunteers of Ireland, formed his right; the King's American Regiment, with Robertson's corps, composed his left; the New York volunteers were in the centre. The South Carolina Regiment and the cavalry were in the rear and formed a reserve.[9]

Such was the impetuosity of the British that, in the face of a destructive discharge of grape, they gained the summit of the hill and pierced the American centre. The militia fell into confusion, their officers were unable to rally them, and General Greene ordered a retreat. The pursuit was continued for nearly three miles. The Americans halted for the night at Saunders' Creek, about four miles from Hobkerk's Hill, and next day proceeded to Rugeley Mills, about twelve miles from Camden. After the engagement the British returned to Camden. The American loss was 300; the British lost 258 out of about 900 who were on the field.[Pg 43]

FOOTNOTES:

[6] "The True History of the Siege of Savannah," published 1780.

[7] "The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America," by Lieutenant-Colonel Tarleton, London, 1787.

[8] Tarleton, p. 461.

[9] "Martial Register," vol. iii. p. 110.

CHAPTER III.

THE RELIEF OF NINETY-SIX, 1781—THE BATTLE OF EUTAW SPRINGS, 1781—REMOVAL TO THE WEST INDIES.

Lord Rawdon was not in a position to follow up his success at Hobkerk's Hill, and on the 3rd of May, 1781, Greene passed the Wateree, and occupied such positions as to prevent the garrison at Camden obtaining supplies. Generals Marion and Lee were also posted at Nelson's Ferry, to prevent Colonel Watson, who was advancing with 400 men, from joining Lord Rawdon, and Watson was obliged to alter his route. He marched down the north side of the Santee, crossed it near its mouth, with incredible labour advanced up its southern bank, recrossed it above the encampment of Marion and Lee, and arrived safely with his detachment at Camden on the 7th of May.

Thus reinforced, Lord Rawdon determined to attack Greene, and, on the night of the 8th, marched from Camden with his whole force. Greene, who had been informed of this movement, passed the Wateree and took up a strong[Pg 44] position behind Saunders' Creek. Lord Rawdon followed him and drove in his outposts, but, finding the position was too strong for his small force, he returned to Camden.

Camden being too far advanced a post for Lord Rawdon to hold with the few troops at his disposal, he evacuated it on the 10th of May, and retired by Nelson's Ferry to the south of the Santee, and afterwards to Monk's Corner. In the meantime, attacks were made on the British posts in Georgia, Augusta itself being taken on the 5th of June, while the post of Ninety-six in South Carolina was closely invested by General Greene with the main American army in the Southern States.

About this time, a change took place in the South Carolina Regiment. Lord Rawdon, in a letter to Lieutenant-General Earl Cornwallis, dated Charlestown, June 5th, 1781, speaks of the difficulty which he has experienced in the formation of cavalry, and goes on to say that the inhabitants of Charlestown having subscribed 3000 guineas for a corps of dragoons, out of compliment to those gentlemen "I have ordered the South Carolina Regiment to be converted into cavalry, and I have the prospect of their being mounted and completely appointed in a few days."

On the 3rd of June, Lord Rawdon had received considerable reinforcements from England, and on the 9th he left Charlestown with about 2000 men, including the South Carolina Regiment in its new capacity, for the relief of Ninety-six. In their rapid progress over the whole extent[Pg 45] of South Carolina, through a wild country and under a burning sun, the sufferings of the troops were severe, but they advanced with celerity to the assistance of their comrades. On the 11th of June, General Greene received notice of Lord Rawdon's march, and immediately sent Sumpter with the whole of the cavalry to keep in front of the British army and retard its progress. Lord Rawdon, however, passed Sumpter a little below the junction of the Saluda and Broad Rivers, and that officer was never able to regain his front.

In the meantime, the Americans were pushing hard the garrison of Ninety-six; they were nearly reduced to extremities, and in a few days must have surrendered; but the rapid advance of Lord Rawdon left Greene no alternative but to storm or raise the siege. On the 18th of June, he made a furious assault upon the place; but, after a desperate conflict of nearly an hour, was compelled to retire. Next day he retreated, crossing the Saluda on the 20th, and encamping at Little River.

On the morning of the 21st, Lord Rawdon arrived at Ninety-six, and the same evening set out in pursuit of Greene, who, however, retreated; and Rawdon, despairing of overtaking him, returned to Ninety-six. He now found it necessary to evacuate that position and contract his posts; and, having destroyed the works, he marched towards the Congaree. There, on the 1st of July, while out foraging, two officers and forty dragoons of the South Carolina[Pg 46] Regiment were surrounded and taken prisoners by Lee's Legion. This blow sadly crippled Lord Rawdon, who was much in need of cavalry, and two days later he retreated to Orangeburgh.

The summer heats now coming on, Lord Rawdon proceeded to England on sick leave, leaving Lieutenant-Colonel Stuart in command of the troops in South Carolina and Georgia. The new commander at once proceeded with the army to the Congaree, and formed an encampment near its junction with the Wateree.

Towards the end of August, while Lieutenant-Colonel Stuart was expecting a convoy of provisions from Charlestown, he received information that General Greene, who had been reinforced and was now at the head of 2500 men, was moving towards Friday's Ferry on the Congaree. The American cavalry was so numerous and enterprising that the expected convoy, then at Martin's, fifty-six miles from the British camp, would inevitably fall into their hands unless protected by an escort of at least 400 men; and Lieutenant-Colonel Stuart's force being too small to admit of so considerable a body being detached without risk, he determined to retreat by slow marches to Eutaw Springs, about sixty miles north of Charlestown, and meet the convoy on the way.

General Greene followed the retiring British, and, on the 7th of September, arrived within seven miles of Eutaw Springs. Being there reinforced by General Marion and his[Pg 47] corps, he resolved to attack next day. At six in the morning, two deserters from the American army entered the British camp, and informed Stuart of the approach of the enemy; but little credit was given to their report. At that time Major Coffin, with 140 infantry and 50 of the South Carolina Regiment, was out foraging for roots and vegetables—the army having neither corn nor bread—in the direction in which the Americans were advancing. About four miles from the camp at Eutaw, that party was attacked by the American advanced guard and driven in with loss. Their return convinced Colonel Stuart of the approach of the enemy, and the British army was soon drawn up obliquely across the road on the height near Eutaw Springs.

The firing began between two and three miles from the British camp. The British light parties were driven in on their main body, and the first line of the Americans attacked with great impetuosity. For a short time the conflicting ranks were intermingled, and the officers fought hand to hand. At that critical moment, General Lee, who had turned the left flank of the British, charged them in the rear. They were broken and driven off the field, their guns falling into the hands of the Americans, who eagerly pressed on their retreating adversaries.

At this crisis, Colonel Stuart ordered a strong detachment to take post in a large three-storey brick house, which was in rear of the army on the right, while another occupied an adjoining palisaded garden, and some close underwood.[Pg 48] The Americans made the most desperate efforts to dislodge them from their posts; but every attack was met with determined courage. Four pieces of artillery were brought to bear on the house, but made no impression on its solid walls, from which a close and destructive fire was kept up, as well as from the adjoining enclosure. Almost all the gunners were killed and wounded; and the guns had been pushed so near the house that they could not be brought off. Colonel Washington attempted to turn the British right, and charge them in rear; but his horse was shot under him, and he was wounded and made prisoner. After every attempt to dislodge the British from their position had failed, General Greene drew off his men, and retired to the ground which he had left in the morning. This conflict had lasted nearly four hours. The Americans lost 555, the British 693. The British kept their ground during the night, and next day began to retreat. About fourteen miles from the field of battle, Lieutenant-Colonel Stuart was met by a reinforcement, under Major McArthur, marching from Charlestown to his assistance. Thus strengthened, he proceeded to Monk's Corner.

Eutaw Springs was the last engagement of importance in the southern provinces. The British soon retreated to a position on Charlestown Neck, and confined their operations to the defence of the posts in that vicinity; while in Georgia, the British force was concentrated at Savannah. The surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, in October, 1781,[Pg 49] and the subsequent peace negotiations, put an end to the hostilities in America.

Lieutenant-Colonel Tarleton says: "It is impossible to do justice to the spirit, patience, and invincible fortitude displayed by the commanders, officers, and soldiers during these dreadful campaigns in the Carolinas. They had not only to contend with men, and these by no means deficient in bravery and enterprise, but they encountered and surmounted difficulties and fatigues from the climate and the country, which would appear insuperable in theory and almost incredible in the relation. They displayed military and, we may add, moral virtues far above all praise. During renewed successions of forced marches, under the rage of a burning sun and in a climate at that season peculiarly inimical to man, they were frequently, when sinking under the most excessive fatigue, not only destitute of every comfort but almost of every necessary which seems essential to existence. During the greater part of the time they were totally destitute of bread, and the country afforded no vegetables for a substitute. Salt at length failed, and their only resources were water and the wild cattle which they found in the woods. About fifty men, in this last expedition, sunk under the vigour of their exertions and perished through mere fatigue."

At the cessation of hostilities, the South Carolina Regiment and the Loyal American Rangers were removed to Jamaica, and as they are shown in the Jamaica Almanack[Pg 50] for 1782 as being then in the island, they presumably arrived there about December, 1781. The South Carolina Regiment was probably dismounted, as it is shown as being stationed at Fort Augusta in Kingston harbour. At this time, the reinforcing of the West India Islands by provincial corps was considered most important, and in a letter to Sir Guy Carleton we find the following: "The object of reinforcing those islands is so important, that His Majesty wishes to have it understood that every provincial corps embarking for the West Indies shall immediately be put upon the British Establishment." It was, probably, on some such understanding that the two corps above mentioned proceeded from South Carolina; but the promise, if made, was never fulfilled, and neither of the two ever appeared in any Army List. The following is the list of officers of the South Carolina Regiment given in the Jamaica Almanack:

Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant—Captain Lord Charles

Montagu, 88th Regiment.

Major—James Balmer.

Captains—G.C. Montagu, Robert Palmer, W. Oliphant, W. Lowe.

Lieutenants.

| R. Marshall. | H. Craddock. | — Odonnell. |

| J. Carden. | D. M'Connell. | A. Clerk. |

| H. Rudgley. | P. Sergeant. | J. Petrie. |

| M. Rainford. | J.P. Collins. | — Smith. |

Ensigns.

| W. Splain. | J. Kent. | B. Meighan. |

| — Bell. | — Farquhar. | — Thomas. |

| — Smith. |

The South Carolina Regiment remained in Jamaica until the general disbandment of the provincial corps in 1783. The lieutenant-colonel commandant was given an independent company, and the whites, both officers and men, were pacified with grants of land. The black troopers, however, were a source of difficulty. These troopers, some of whom were originally free, while some had been purchased by the British Government, were in those days of slavery something of a "white elephant" in a large slave-holding colony like Jamaica. The planters, fearful of the consequences of the example to their slaves of a free body of negroes who had served as soldiers, agitated for their removal from the island, but, on the other hand, no other island was willing to receive them. There is no trace of how the difficulty was finally settled, but in a letter, dated War Office, June 15th, 1783, signed R. Fitzpatrick, and addressed to Major-General Campbell, commanding in Jamaica, the receipt of his letter concerning the disbandment of the provincial troops in the island is acknowledged, and the removal of "the blacks of the South Carolina Regiment" to the Leeward command approved of.

Some time, then, in September, 1783, the black troopers were removed to the Leeward Islands, and in the "Monthly[Pg 52] Return of His Majesty's Forces in the Leeward and Charibee Islands, under the command of Lieutenant-General Edward Mathew," we find them formed into a corps, with a body of black artificers, who had served in South Carolina at the sieges of Charlestown and Ninety-six, and thirty-three black pioneers who had been included in the surrender of Yorktown. The following is the state of this corps:

RETURN OF THE BLACK CORPS OF DRAGOONS, PIONEERS, AND ARTIFICERS.

A. Captains.

B. 1st Lieutenants.

C. 2nd Lieutenants.

D. Sergeants Present.

E. Drummers and Trumpeters Present.

F. Present, fit for duty.

G. Sick in Quarters.

H. Sick in Hospital.

I. On Command.

J. Total.

K. Total of the Whole.

| Officers Present. |

D | E | Effective Rank and File. | K | ||||||||

| Where Stationed. | Companies | A | B | C | F | G | H | I | J | |||

| Grenada St. Vincent Grenada |

Capt. Mackrill Capt. Anderson Capt. Millar |

1 1 1 |

- - - |

- 1 - |

3 14 3 |

1 5 - |

25 46 19 |

7 4 4 |

10 - 4 |

23 138 19 |

65 188 46 |

70 209 50 |

| Total | 3 | - | 1 | 20 | 6 | 90 | 15 | 14 | 180 | 299 | 329 | |

The officers of this corps were, according to Bryan Edwards, vol. i. p. 386, taken from the regular army, and the companies were commanded by lieutenants of regulars, having captains' rank. Artificers, it may be as well to observe, were sappers and miners. The Royal Engineers at about this date consisted of various companies of Artificers; later on they were called Sappers and Miners; and, finally, Royal Engineers.[Pg 53]

CHAPTER IV.

THE EXPEDITION TO MARTINIQUE, 1793—THE CAPTURE OF MARTINIQUE, ST. LUCIA, AND GUADALOUPE, 1794—THE DEFENCE OF FORT MATILDA, 1794.